For treating depression, electroconvulsive therapy still beats ketamine

- Ketamine, a recreational drug, is increasingly being used to remedy treatment-resistant depression, with promising results.

- But a systematic review suggests that heavily stigmatized electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is better at reducing depressive symptoms and leads to more cases of remission.

- ECT should probably be getting the same glowing press as ketamine — and arguably more.

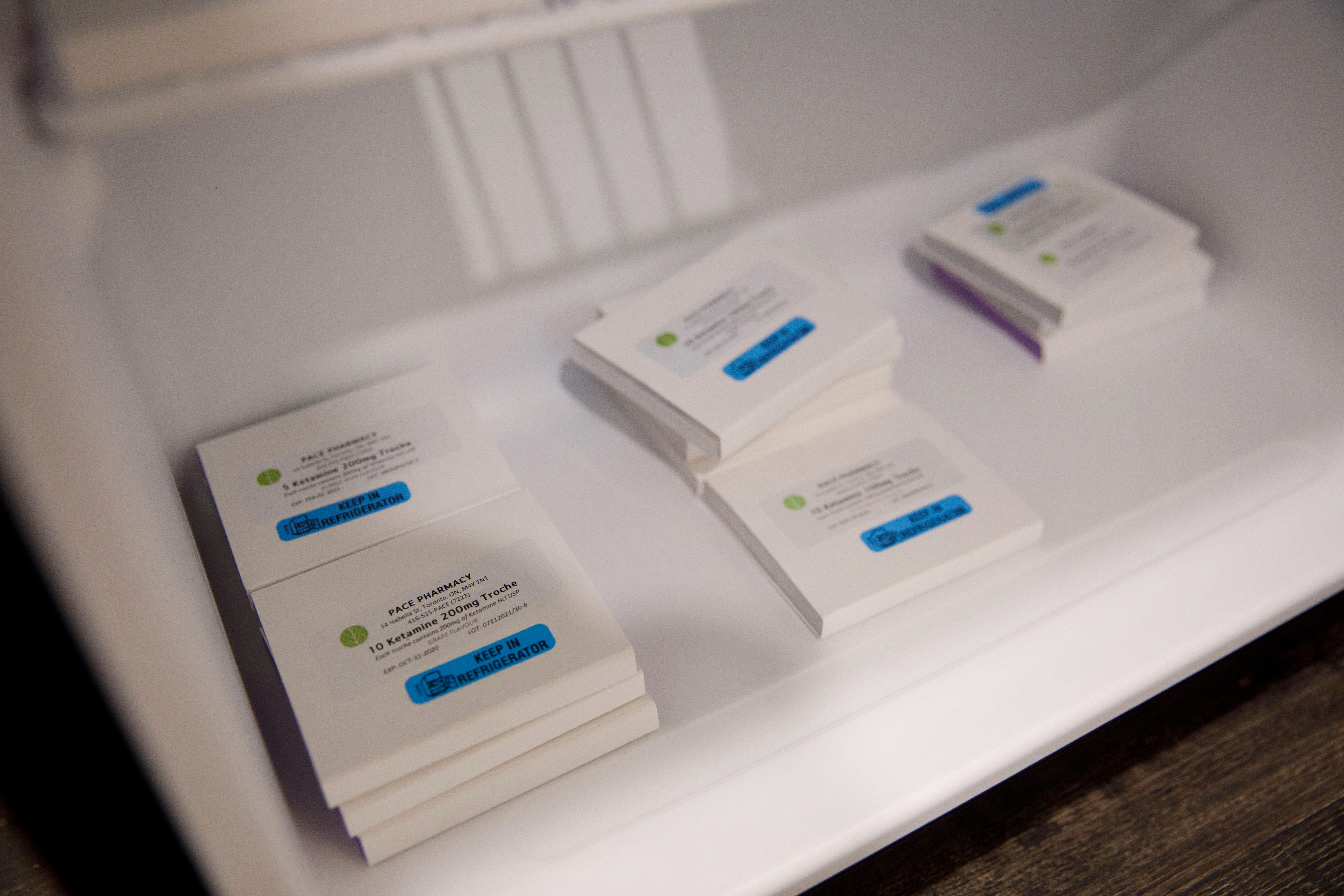

Over the past few years, people suffering from treatment-resistant depression have increasingly turned to ketamine, a recreational “club” drug currently classified as Schedule III by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, to assuage the sadness, anxiety, fatigue, and other debilitating symptoms commonly associated with the disorder.

And ketamine does seem to work pretty well, possibly by influencing a brain chemical called glutamate, which nerve cells use to send signals to other cells. Through intravenous injections or an FDA-approved nasal spray, administered in a supervised, controlled setting one or two times a week, often for six to eight weeks in sessions lasting a couple hours, patients can experience rapid and lasting improvement of their depression symptoms — sometimes in as little as 40 minutes. Conventional antidepressants can take weeks to have an effect.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Ketamine’s glowing press stands in stark contrast to a treatment that’s been around a lot longer and is administered in a similar manner. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has been portrayed in various media formats (most memorably in the film One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) as a barbaric treatment in which patients are subjected to brutal shocks in an attempt to “reset” their brains, often leaving them addled, yet docile. While those depictions may have had a smidgen of truth to them in decades past, modern ECT, in which patients under general anesthesia are given a mild seizure for a minute or so in six to 12 clinical sessions over the span of a few weeks, is both benign and effective. Apart from some side effects that persist for a few hours after their sessions, ECT patients suffer no ill effects and can see their depression improve or even resolve after about six bouts.

In fact, as a new systematic review published to JAMA Psychiatry shows, electroconvulsive therapy is even more effective than trendy ketamine.

An international team of researchers analyzed all of the clinical research comparing ECT directly to ketamine for the treatment of depression. There were six trials in total conducted on 340 subjects in hospitals in Sweden, Germany, Iran, and India. In every single trial, ECT topped ketamine at reducing the severity of depression symptoms. It also yielded higher remission rates.

Moreover, as UConn School of Medicine Psychiatric Epidemiologist T. Greg Rhee said in a statement, the benefits were experienced broadly:

“We found no differences by age, sex, or geographic location. So we could say anyone who is ECT eligible will benefit.”

Side effects differed between the two treatments. ECT patients were more likely to experience headache and muscle pain, while ketamine users suffered more from blurred vision, vertigo, diplopia, and dissociation.

Though less effective, ketamine treatments tended to be better tolerated, with fewer adverse effects overall. They also eased symptoms more quickly.

Two large clinical trials comparing ketamine and ECT for the treatment of depression, targeting over 600 participants, are currently underway in North America. So we should have more data in the coming years.

For now, the evidence indicates that ECT should probably be getting the same attention as ketamine – and arguably more – for its ability to remedy hard-to-treat depression.

“People are still skeptical of ECT, perhaps because of stigma,” Rhee said. “We need to improve public awareness of ECT for treatment-resistant depression.”