The secret life of maladaptive daydreaming

- Maladaptive daydreamers can experience intricate, vivid daydreams for hours a day.

- This addiction can result in disassociation from vital life tasks and relationships.

- Psychologists, online communities, and social pipelines are spreading awareness and hope for many.

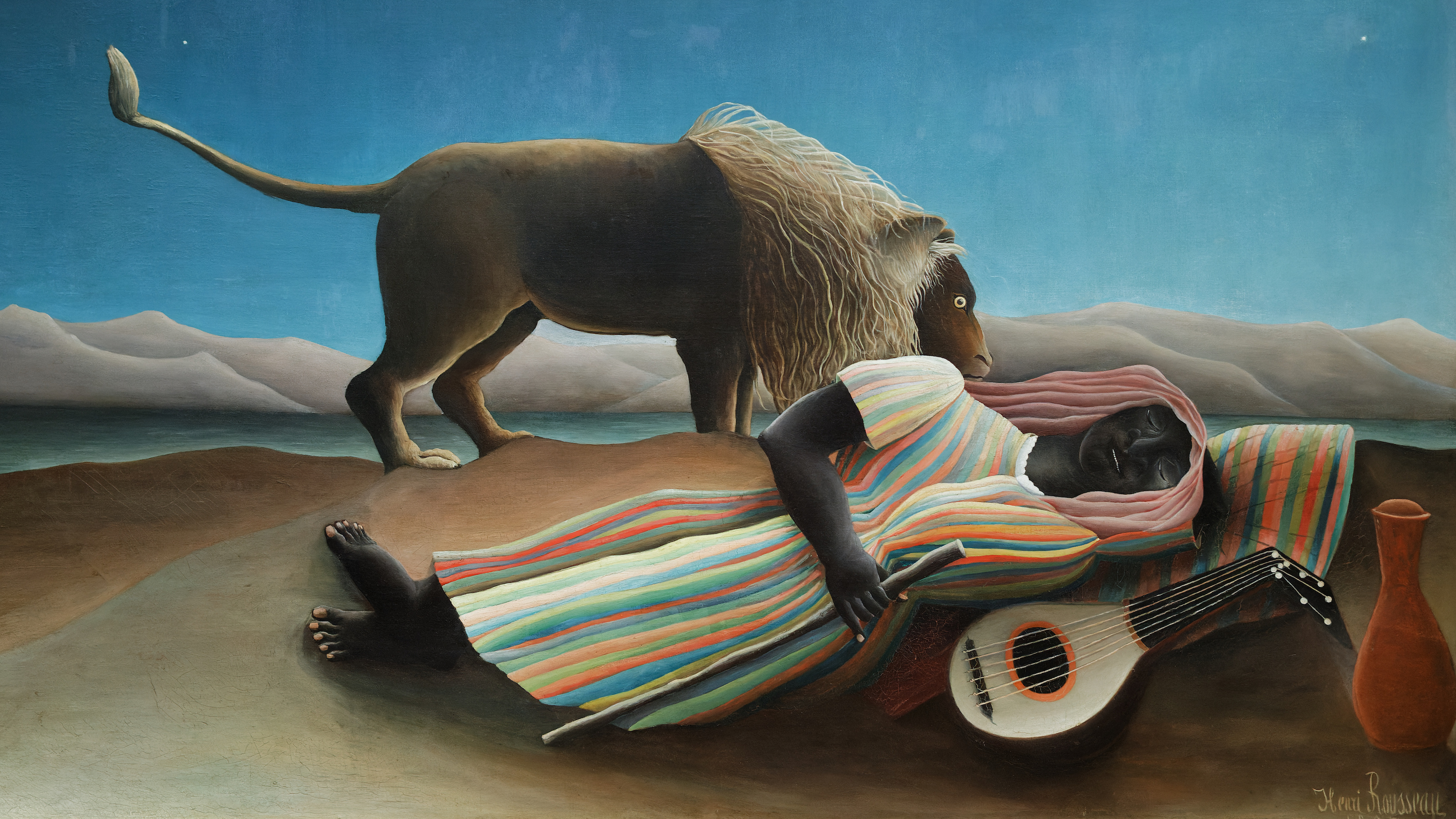

James Thurber’s short story The Secret Life of Walter Mitty follows its mild-mannered protagonist through another mundane day of thankless chores. But Mitty is a daydreamer. He spices up his humdrum existence—and, thankfully, the story itself—through fantasies. Real-world events cause Mitty to imagine he’s an ace hydroplane pilot, a brilliant surgeon, and an assassin on trial.

Thurber’s character fits many readers like a glove because, as science has discovered, we all have a little Walter Mitty in us. Research suggests that our minds wander close to 50% of the time, and we use these mental getaways to imagine our lives in all manner of fun and fanciful scenarios. We fantasize about the perfect meet-cute, or starting an exciting new career, or what we’d do with superpowers, or unbridled sexual encounters. Mostly it’s sex.

And despite admonishments from our Victorian-styled teachers and supervisors, a mind in the clouds is associated with a bevy of cognitive benefits. These include greater creativity, improved productivity, better problem-solving, and progress toward goals. Daydreaming is, in short, a virtue.

An indulgence of the mind

Except when it isn’t, and here the darker undertones of Thurber’s story come into play. It’s hinted that Mitty may not be enjoying playful escapism but suffering from an uncontrollable urge to disassociate from his life, his responsibilities, and his relationships. Today, psychologists are researching whether such a Mittyesque existence may be the result of a new disorder known as maladaptive daydreaming.

Daydreaming is an indulgence of the mind and imagination, one provided courtesy of the default mode network, a network of interacting brain regions that is active even when the conscious mind is not. But like so many of life’s indulgences—wine, steak dinners, video games, and even exercise—too much daydreaming can be harmful to our well-being. When daydreaming crosses that threshold, it can be considered maladaptive.

This disorder was first identified by Eli Somer, a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Haifa, School of Social Work, in a 2002 paper. That paper looked to six patients in a trauma center whose daydreaming habits replaced human interactions or interfered with their standard life functions, such as going to school or holding down a job.

Since then, other case studies have looked at maladaptive daydreamers and compiled a list of potential symptoms. These include vivid, richly detailed daydreams; abnormally long daydreaming sessions; daydreams triggered by real-life events; daydreaming sessions that interrupt sleep; and repetitive motions or whisperings while daydreaming. On average, one study reported, maladaptive daydreamers spend four hours a day housed in their imaginations.

“This is not like rehearsing a conversation that you might have with a boss,” Somer told CNN. “This is fanciful, weaving of stories. It produces an intense sense of presence.”

While such symptoms are common, though not comprehensive or guaranteed, how maladaptive daydreams manifest is naturally individual to the dreamers. In one case study, researchers analyzed the diary of a man codenamed Peter. He described investing as many as 14 hours a day online. The news and images he happened upon would trigger related fantasies. For example, he may envision himself as a multimillionaire genius who could prevent bad news from occurring or self-insert himself into the power fantasies of superhero movies or police procedurals for hours at a time.

“When I felt this pain as a child, I started imagining how things could be different. I created stories which never happened. To suppress that pain I would hug my pillow or quilt, thinking I was being comforted by someone else,” Peter wrote.

In an interview with CNN, Cordellia Rose described her maladaptive daydreaming like a drug and noted that her daydreams developed into intricate storylines that could last for years. These stories proved so distracted that she was unable to complete everyday tasks such as driving lessons.

“You get hooked on it, because it can be like an action movie in your head that’s so gripping that you cannot turn off,” Rose told CNN. “This [condition] needs to be public, because these are people suffering, and badly.”

To be clear, maladaptive dreaming is not a psychotic disorder like schizophrenia. Daydreamers such as Peter and Rose are aware that their fantasies are as unreal as they may be unrealistic. Because of this, many maladaptive dreamers understand the difficulties they face and the real-life losses they have endured for the sake of their fantasies.

Researchers don’t have a standard diagnosis or treatment for maladaptive daydreaming because they aren’t yet sure it’s a unique psychological condition. Maladaptive daydreaming has not been included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition—blessedly abbreviated as the DSM-5—the definitive book on mental disorders. To date, there isn’t enough evidence to determine if maladaptive daydreaming is a separate condition or a manifestation of an already listed disorder.

Somer has developed a 14-point scale to help people determine whether they are experiencing maladaptive-daydreaming symptoms, but the results only indicate whether an individual should seek help. They provide no formal diagnosis.

Also, maladaptive daydreaming is often expressed alongside other conditions, such as anxiety disorders, dissociative disorders, attention deficit disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. And the researchers of Peter’s case study noticed a striking similarity between his condition and those with behavioral addiction response—including analogous responses with preoccupation, mood modification, tolerance, and withdrawal. It may be that maladaptive daydreaming is an expression of these, or other, disorders.

It’s worth noting that similar empirical hurdles exist for other well-known, though not formalized, disorders. Orthorexia, sex addiction, misophonia, internet addiction, and parental alienation syndrome are all likewise absent from the DSM-5. For maladaptive daydreaming and these other conditions, it’s simply a case of more evidence and research needed before a determination can be made.

The right label

The question of labeling is a tricky one—not only from a medical point-of-view but also a prosocial one. Some people find having a recognized condition validating; they feel it promotes social acceptance and makes seeking treatment easier. Others find such labels stigmatizing and restricting.

But the question of how to label something is an academic one. It isn’t to say that the experience doesn’t exist. It does, and whether maladaptive daydreaming ultimately enters the DSM-5 or not, awareness is growing. Online communities now exist to give support and spread awareness. And regardless of a condition’s presence in the medical literature, if symptoms disrupt work, school, or social lives, help should be sought.

Thanks to the efforts of psychologists and the community, maladaptive daydreaming, unlike Thurber’s literary creation, is no longer “inscrutable to the last.” And those who suffer it are no longer relegated to a firing squad of their own mind but can find the help the need.