Why do some species evolve to miniaturize?

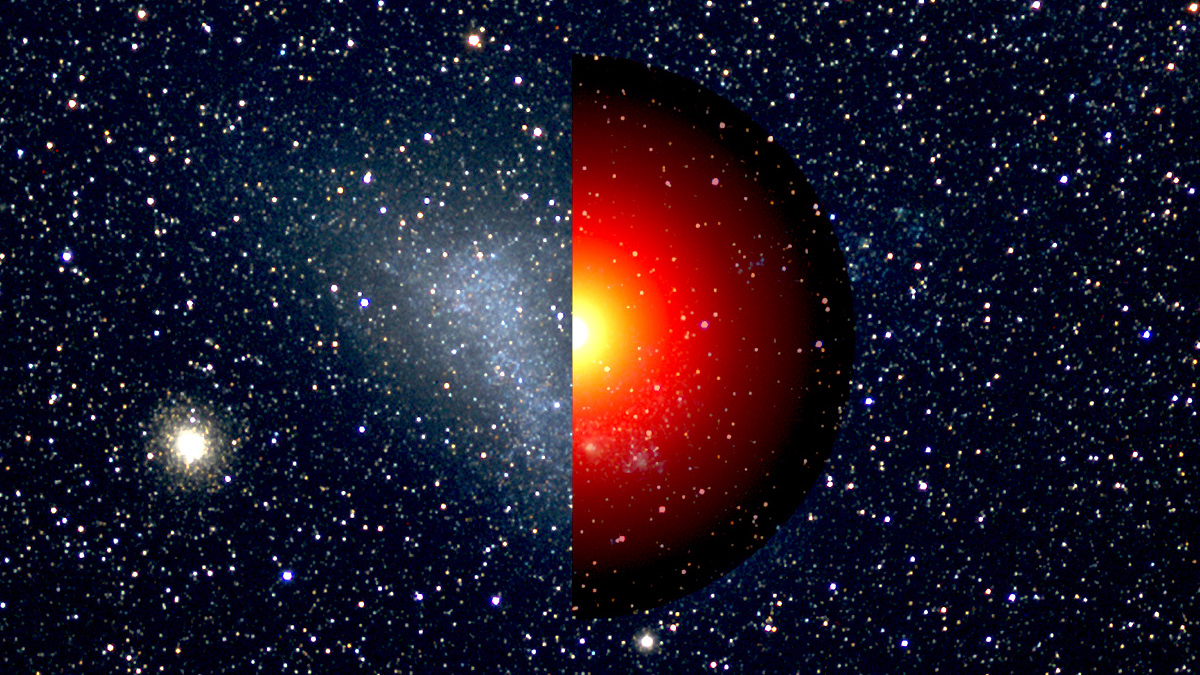

Credit: Frank Glaw

- Brookesia nana, the nano-chameleon, may be the smallest vertebrate ever discovered.

- The “island rule” states that when new species migrate to islands, they may shrink or grow as they evolve to fill new ecological niches.

- It remains unclear whether the island rule can explain the nano-chameleon or nature’s other extreme miniaturizations.

The nano-chameleon (Brookesia nana) is one of the latest contenders for the title of the world’s smallest reptile and amniotic vertebrate. Found in a mountainous region in northern Madagascar, the males of this diminutive species sport a body size of 13.5 mm, meaning one could comfortably stand on the end of your finger.

Its wee challenger is the Jaragua dwarf gecko (Sphaerodactylus ariasae). These pocket-change-sized geckos—the genus is often pictured snogging the minted portraits of past presidents—come in at 16 mm from nose to tail. They were discovered in 2001 on Isla Beata, a small, forested Caribbean island just south of the Dominican Republic.

The title of the world’s smallest, however, is difficult to award thanks to sexual size dimorphism. As Dr. Mark Scherz, a herpetologist and evolutionary biologist, pointed out on his blog, nano-chameleon females are significantly larger than their male counterparts or Jaragua dwarf gecko females. “As a result, whether or not the new species is considered the smallest amniote in the world depends on whether we define that based on the male or female body size, or the midpoint of the two. It turns out this is quite a common problem in other species with size dimorphism as well, such as frogs,” Scherz writes.

Beyond their shrimpy stature, these and other miniaturized species have another thing in common: They live on islands. That fact may explain why evolution has pushed them to shrink in a world full of giant competition.

Because of their geographic isolation, islands can have powerful effects on the evolution of their residential species. The massive Komodo dragon prowls its namesake island. The Barbados threadsnake is thin enough to slither through a straw. And the fossil record recounts a history of unusually sized and bedecked creatures who established homes far from the mainland, such as the Hoplitomeryx of the Mikrotia fauna.

The “island rule”

One hypothesis for evolution’s insular experimentation is the “island rule.” The rule states that after establishing themselves on an island, smaller species will tend to evolve into oversized versions of their mainland ancestors. Meanwhile, larger species will tend to evolve into smaller variations. These processes are known as insular gigantism and insular dwarfism, respectively. They do this to fill the ecological niches available to them, which often differ from those they filled on the mainland.

The rule was first formulated by evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen and based on a 1964 study by mammologist J. Bristol Foster—which is why it is also known as Foster’s rule. Since then, many observational studies have corroborated the island rule, and there is even evidence to suggest that new species introduced to islands will, for a time, evolve more rapidly to fill available niches.

A flock of migrant birds, for example, may find an island’s lack of mammalian and reptilian predators opens the ground-living niche once forbidden to them. Such birds would then be free to grow larger, forage below the canopies, and lose the ability to fly.

This appears to be the origin story for New Zealand’s flightless birds including the giant moa, which, at 6 feet tall, is the tallest bird on record. This megafauna enjoyed all the benefits of being large and in charge: fewer predators, wider ranges, access to more food and more varied types, and the ability to better survive trying times. The species enjoyed island life until roughly 600 years ago when humans arrived on the scene and hunted them to extinction.

Conversely, large species may find island living restrictive as there’s less room or food when compared to their mainland nurseries. Because of this, evolution may select for smaller body sizes as such bodies require less energy, and therefore fewer resources, to survive and reproduce.

This is the theory behind the miniaturization of the Channel Islands’ pygmy mammoths. As the story goes, in the search for food, a herd of Columbian mammoths embarked on a journey to the super island Santaroasae. Over time, the island was cut off from the mainland. Food became scarce, and smaller mammoths had an easier time surviving and reproducing, thus passing on their Shrinky-Dink genes. Thanks to a lack of oversized predators, such evolution proved fruitful, and in less than 20,000 years, the giant Columbian mammoths evolved into a new species—the (relatively) pint-sized, 6.5-foot-tall pygmy mammoths.

To be clear, the island rule doesn’t state that any species that washes ashore must go either Lilliputian or Brobdingnag. It only states that if an ecological niche becomes available and improves survival and reproductive success, then such a change is likely.

Such constrained growth may be the cause of the Jaragua dwarf gecko’s bantam evolution. The gecko eats tiny insects and may be filling a niche that’s unavailable on the North American continent with its many, many insectivores. In fact, the island rule may explain why islands are so rich with endemic species—particularly the Caribbean, which is considered a biodiversity hotspot.

Of course, scientific rules are only provisional, and scientists are prepared to revise or completely disregard a hypothesis should new evidence appear. In a field as new as biogeography, the question of whether the island rule is truly a “rule” remains an open and hotly debated question.

One systematic review found empirical support for the island rule to be low, while another analysis argued the rule is simply a recognition of “a few clade-specific patterns.” The latter’s authors conclude that “[i]nstead of a rule, size evolution on islands is likely to be governed by the biotic and abiotic characteristics of different islands, the biology of the species in question and contingency.”

That brings us back to the recently discovered nano-chameleon. While it seems to follow the island rule—Madagascar being an island known for its rich biodiversity—there is a wrinkle. The species’ closest relative lives right next door. Brookesia karchei is near twice the size of the nano-chameleon but ranges in the same mountains on mainland Madagascar.

If the nano-chameleon evolved to fill an ecological niche, why didn’t those same environmental pressures miniaturize the karchei chameleon? If not the island rule, what did lead to the nano-chameleon’s smaller size? As is often the case in science, further evidence may one day answer these questions.