New tardigrade species withstands lethal UV radiation thanks to fluorescent ‘shield’

Credit: Suma et al., Biology Letters (2020)

- Apparently, some water bears can even beat extreme UV light.

- It may be an adaptation to the summer heat in India.

- Special under-skin pigments neutralize harmful rays.

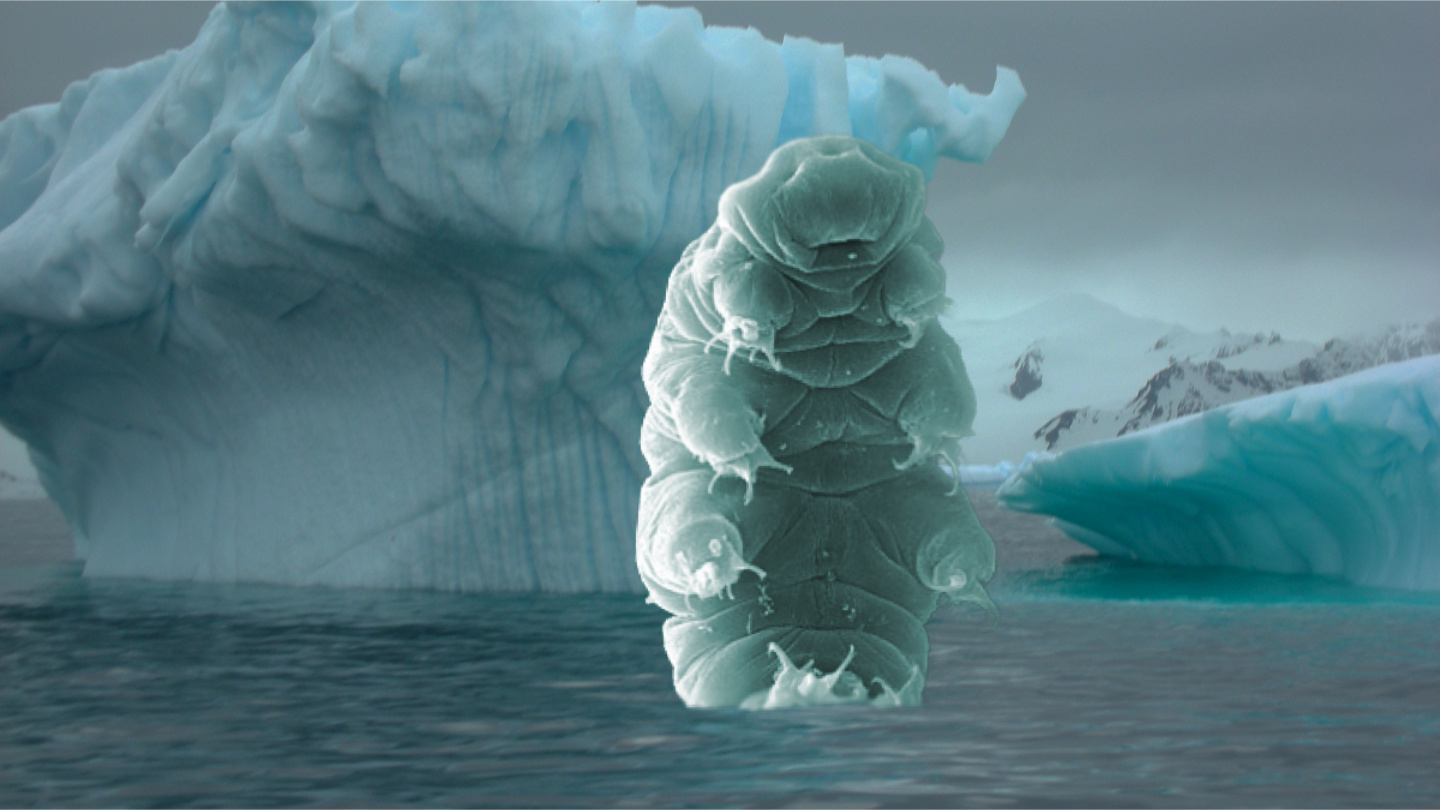

Many of us consider ourselves tardigrade, or “water bear” fans. These microscopic buggers — actually not bugs at all but their own distinct phylum with over 1,000 members — are unbelievably hardy in spite of their diminutive stature: They range from just 0.5 to 1 millimeter in length.

Tardigrades survive in all sorts of conditions that should really spell their doom. They’re basically found everywhere on Earth, and last spring an Israeli lunar lander may have inadvertently dumped a bunch of them on the moon where they may well be happily going about their water bear business.

Almost nothing kills them, except for super-extreme blasts of ultraviolet (UV) light that would be deadly to most organisms. Or so it seemed, until researchers came across some reddish-brown eutardigrades living in moss on a wall in Bengaluru, India. These, it turns out, don’t care that much about even staggering amounts of germicide-level UV. The scientists concluded that what they were dealing with was an undocumented member of the Paramacrobiotus genus.

Score one more for our wee heroes.

The research is published in the Royal Society Biological Letters.

3D illustration of a tardigradeCredit: Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock

It seems at times like scientists enjoy playing the “let’s see if this kills them” game with tardigrades, a game that humans usually lose. After searching the campus of the Indian Institute of Science, researchers gathered some water bears and brought them back to the lab to see what they could handle.

The scientists found that after they exposed Hypsibius exemplaris tardigrades to very high doses — 1 kilojoule (kJ) per square meter — of UV light for about 15 minutes, they would in fact die over the next 24 hours. However, when they aimed the same blasts at the reddish-brown tardigrades…nothing. The humans even quadrupled the UV intensity and, nope, they tracked the water bears for 30 days, and a majority of them, 60 percent, were still fine.

As is often the case with tardigrades, the question is how?

Tardigrade’s normal appearance (left), and under inverted fluorescence (right)Credit: Suma et al., Biology Letters (2020)

When the researchers examined the tardigrades under an inverted fluorescence microscope they found that when they were exposed to UV light, they became blue. The researchers’ hypothesis is that these tardigrades carry fluorescent pigments beneath their skin that they deploy as necessary to transform UV light into simple benign, blue light. It may be that this ability has emerged as an evolutionary response to southern tropical India’s often-extreme heat. The study says that typical summer-day UV levels in this region are about 4kJ per square meter.

Of the 40 percent of the reddish-brown tardigrades that had died before 30 days — mostly after about 20 days — the scientists concluded they had less pigment with which to neutralize UV light.

When the scientists extracted the pigment from the UV champions and coated some Hypsibius exemplaris tardigrades with the stuff, their resistance to UV exposure was also enhanced, boosting their survival rate to almost twice that of their uncoated brethren.

Autofluorescence has been found in other animals — parrots, scorpions, chameleons, and frogs, among others — so it’s not completely unheard of. In parrots, for example, autofluorescence is hypothesized to be involved in tweaking coloration during mating rituals. Still, surprise, tardigrades seem to be putting it to unusual use by employing it for UV protection.