Why do some people love cringe comedy while others can’t stand it?

- Cringe comedy is one of the most successful genres in film and TV, yet some people either don’t get it or actively dislike it.

- We find things more or less cringeworthy depending on our “social closeness” with that item, e.g. if we know a boss who speaks in that way.

- One major theory of cringe is that it’s a form of venting social anxiety; it allows us to enjoy the violation of a social norm in a safe setting.

Some people really don’t enjoy cringe comedy. Others just don’t get it. When shows like The Office and Curb Your Enthusiasm first came out, the jokes were lost on many people — or the awkwardness was just too much to bear. After all, what’s so funny about socially awkward, publicly embarrassing situations?

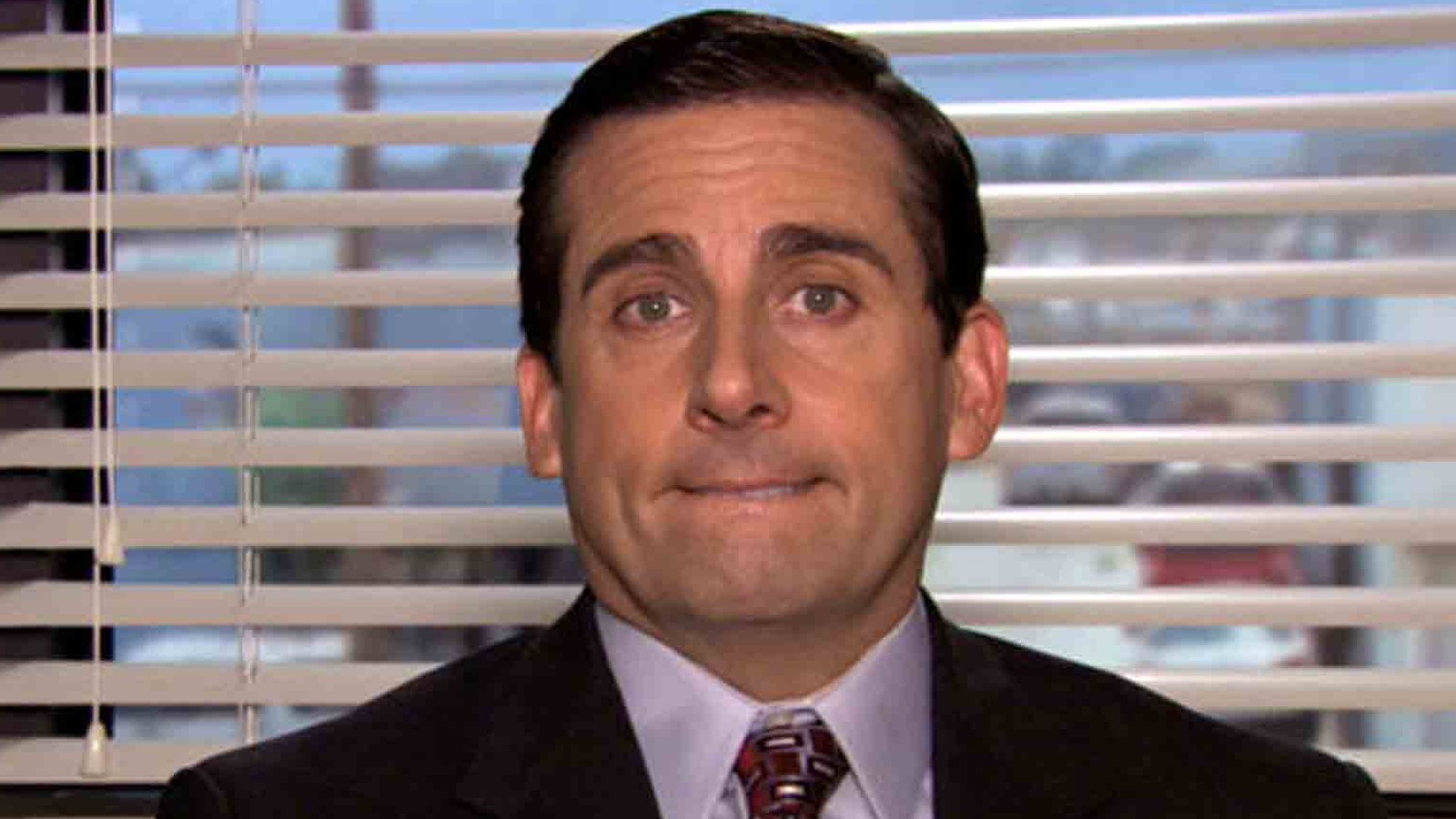

Clearly something. The success of cringe comedy in TV, film, and countless social media channels proves that many of us find delight in other people’s awkwardness. But what’s less clear is how cringe comedy works, and why some people relish in the secondhand embarrassment of watching Michael Scott or Nathan Fielder while others find it excruciating or boring.

The history of cringe comedy

As a genre of comedy, cringe is very old. It could be argued that cringe is present in certain elements of slapstick humor, in that we laugh at someone’s humiliation or misfortune. Indeed, there’s a large element of schadenfreude to cringe comedy, where we take pleasure in witnessing the discomfort of others.

But there’s something noticeably different between laughing at Mr. Bean or Laurel and Hardy and the cringe comedy of today. The ever-resourceful German language provides a still better word: fremdschämen, which is the feeling of embarrassment you get when watching someone behave in an embarrassing way (it’s a combination of the words “external” and “to be embarrassed”).

The difference between slapstick or schadenfreude and cringe is that the former feels much more detached, where we’re laughing at someone. Meanwhile, the latter feels personal — sometimes empathetic. It’s as if we’re embodying the cringeworthy character (or at least feel as if we’re in the same room) and living through their embarrassment.

While “mockumentaries” like This is Spinal Tap paved the way, it wasn’t until the 2000s that cringe comedy really took flight. Comics like Ricky Gervais (The Office), Sasha Baron Cohen (Ali G and Borat), Larry David (Curb Your Enthusiasm), and Steve Coogan (Alan Partridge) led the vanguard in social awkwardness. Their successes spawned the next generation of programs like Girls, Peep Show, and Nathan For You. Today, cringe comedy is everywhere. But what makes it work?

The science of cringe comedy

Humans are social animals, wired to live in packs and function in societies. We are, as developmental psychologist Michael Tomasello puts it, an “ultra-social animal” that’s highly sensitive to emotions like shame, embarrassment, and cringe. We have developed complex forms of social etiquette that help us interact with each other. To follow social etiquette, we have evolved a finely tuned sense of social awareness.

Cringe comedy seems to exploit that awareness. We may enjoy it because it allows us to simulate unusual social situations and witness their consequences without actually having to experience them in the real world. In this way, cringe comedy may help us strengthen a kind of defense mechanism, as media researcher Marc Hye-Knudsen wrote in a 2018 paper:

“By immersively simulating social worst-case scenarios, they prepare us for the cringe of our own lives, better equip us to avoid it, and even provide us with strategies to pursue once it occurs. If, as Gervais supposes, we all like [David Brent, the boss character in the British version of The Office] want to be loved, respected, and thought interesting, then watching The Office provides us with salient examples of how not to achieve this. By violating all the unspoken social norms of the office environment, David makes them salient and allows us to vicariously experience the intense embarrassment that comes with disregarding them.”

But what accounts for the differences in people’s degree of fremdschämen, or empathetic embarrassment? One argument is that we feel embarrassed for those people we feel a “social closeness” with. There’s research to show that we only find cringeworthy those contexts or people we can empathize with or relate to. We experience cringe when someone sings loudly in public, tells an inappropriate joke, or brags about their sexual exploits because we all know people like that. It’s relatable.

The psychologist and author Oliver Burkeman coined the term “easily empathetically embarrassed” people. Burkeman cites a 2011 study, and offers the idea that people who are not EEE are simply wired that way. As he writes: “…there’s a significant correlation between what the researchers labeled “vicarious embarrassment” and a generally high capacity for involvement in the emotional lives of others.” The corollary of this argument is that those who experience greater degrees of cringe are more receptive to others. They’re more empathetic.

Venting social anxiety

In any case, there’s a difference between experiencing cringe and finding it funny. One of the most likely reasons why people find cringe comedy funny is known as the “benign violation hypothesis.” According to this theory, we laugh at moral or social violations which are also benign (no real person is hurt, for instance) and safe (they’re not happening to me!). Of course, as noted above, for cringe humor to work we must have a degree of “social closeness” to the cringe comedy — it has to relate to our everyday lives in some way.

The idea behind this is that when we laugh at cringe comedy, we are reestablishing ourselves on the “right side” of various social norms or taboos. When we laugh at an inappropriate, ignorant, or ridiculous comment, we’re actually adopting the role of policeman and gatekeeper. We know that these are the rules and can sense when someone has broken them, and we laugh to relieve our own sense of social insecurity or anxiety. It’s why the laughter from cringe comedy is of a different kind to other types of laughter. Cringe is hugely funny (for some people), but it comes laced with a slight nervous edge — a tension in the body, an increased heart rate, and the involuntary “oh no!” noises we give out.

The contemptuous and the empathetic

What these various responses to cringe tell us is that there might be more than one thing going on here. Sometimes, when we enjoy cringe humor, we empathize with the events. Watching a mild social faux pas — a joke that lands badly or someone wearing the wrong clothes to party — are funny because we can relate to these moments. This sense of embodying their embarrassment (or shame), this fremdschämen, we could call empathetic cringe comedy.

But as Natalie Wynn, who runs the YouTube channel ContraPoints, argues, this kind of cringe comedy should be separated from another kind: contemptuous. As she puts it, “Contemptuous cringe, on the other hand, involves an emotional distancing from the person you’re cringing at. Just like with compassionate cringe, you perceive that the person is embarrassing themselves, but instead of feeling that embarrassment on their behalf, you feel annoyance and disgust at them, and maybe even a little schadenfreude.”

The affective response of empathetic cringe is different to the more sneering one of contemptuous. It also affects the scripting and setup of a show or movie. With empathetic cringe, the design is to create situations as many viewers can relate to as possible — those Bridget Jones moments that speak to us. With contemptuous cringe, as Wynn puts it, we are invited to feel contempt.

Where does cringe punch?

There’s a lot of work and discussion in recent years about “punching up” or “punching down” in comedy. That is to say, are the laughs gained from mocking marginalized and disempowered groups or those who are decidedly better off that we are? It’s generally supposed the latter is fine, while the former is akin to bullying.

So, where does cringe fall? It might be argued that empathetic cringe — the kind where we relate with the situation — is its own thing altogether; in some way, it could be viewed as us mocking ourselves (as imagined in the situations we’re witnessing). But contemptuous cringe has a darker side. Sometimes, when a producer or comedian showcases a “cringe” moment, they are actually manufacturing or inventing contempt.

As Wynn argues, this is not always so benign. When we are invited to sneer and laugh at “SJW Cringe Compilations” or the weakness in “Screeching Feminists,” what are the implications to that? That “social justice” is embarrassing? That feminism is shameful?

Comedy, satire, and humor have always been politically charged. When we laugh at something, we ridicule it and diminish it — that’s why it’s a great defense mechanism, and the best way to defeat boggarts. But when we laugh at those things that ought to really be important, what damage does that do to the values we want to hold?

Jonny Thomson runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.