The “Düsseldorf patient”: A third person may also be in HIV remission

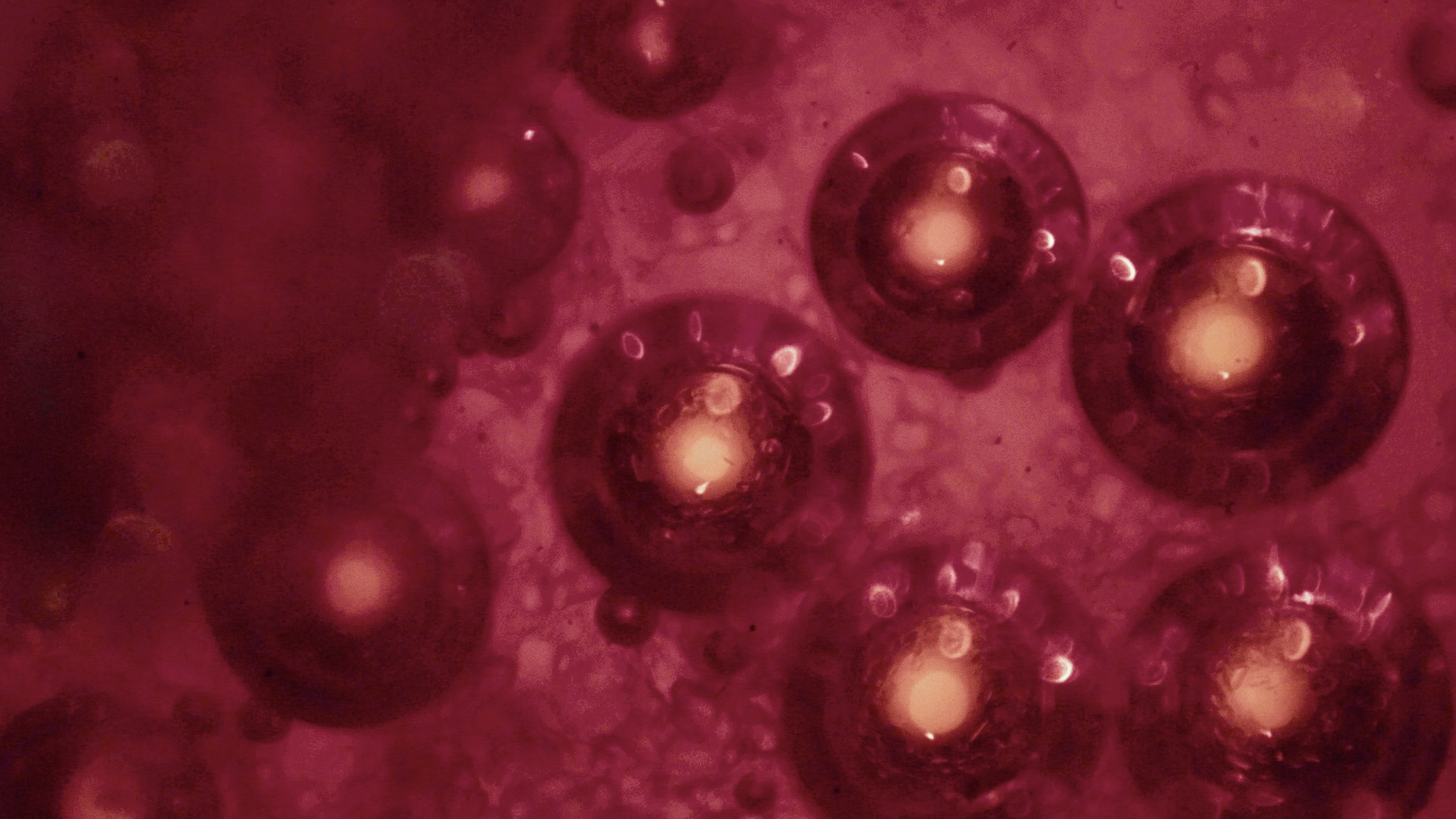

Image source: Shutterstock

- Timothy Brown became the first person to be cured of HIV in 2007.

- Recently, it’s been reported that a patient known as “the London patient” has also lost any trace of the HIV virus in their system.

- Now, a third patient appears to be in HIV remission known as “the Düsseldorf patient.”

Recently, the New York Times reported that for the first time in over a decade, a person with HIV has been cured of the deadly virus. Now, it’s come to light that another patient—the third in history—has been cured of HIV as well.

We first learned that curing HIV was possible in 2007, when a patient known initially as “the Berlin patient,” was diagnosed with both leukemia and HIV. The patient, whose name is Timothy Ray Brown, received a bone marrow transplant to treat his leukemia; after this treatment, Brown’s doctors discovered that his HIV had been cured as well.

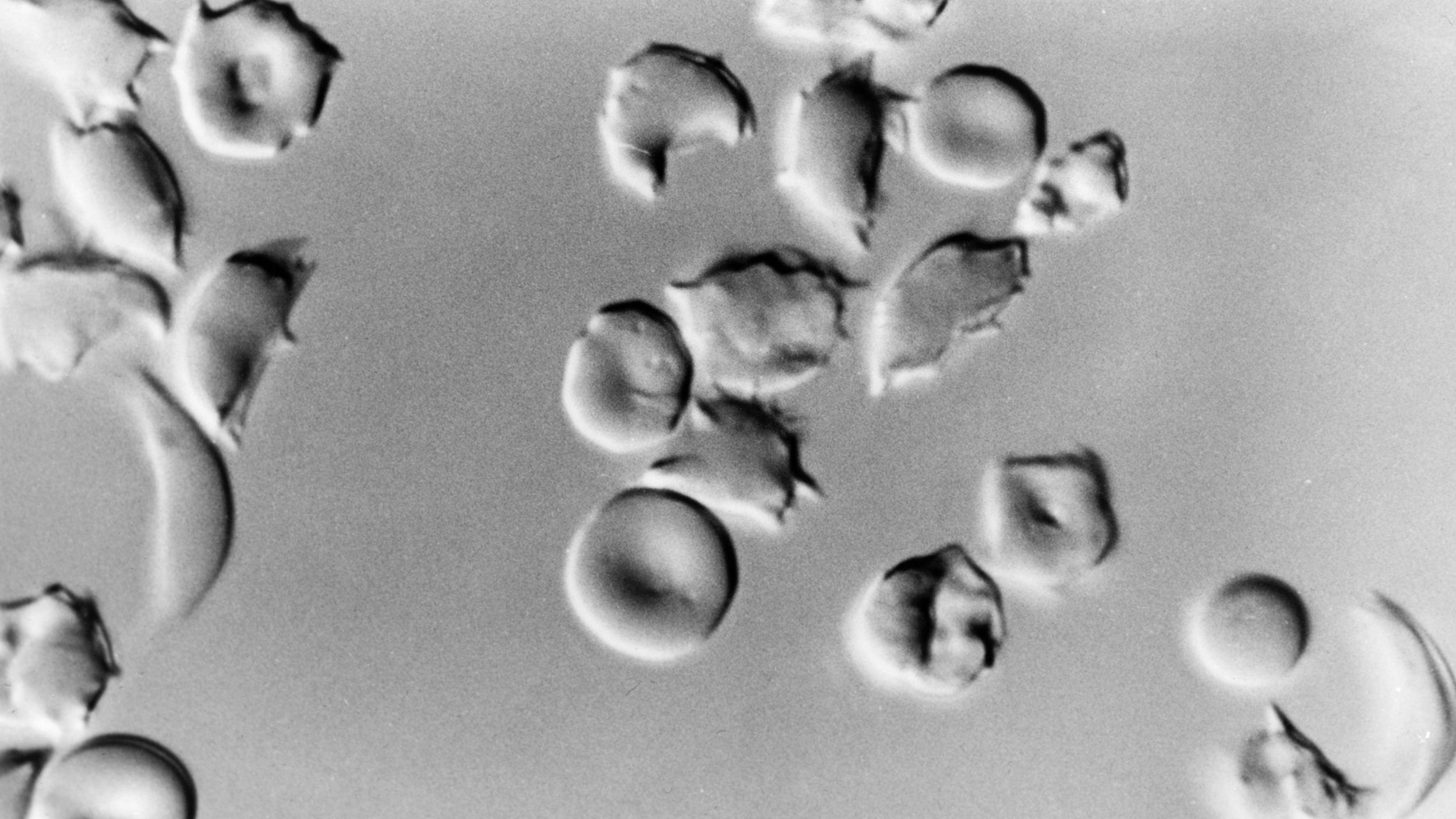

Leukemia is a cancer of the bone marrow, which is why Brown needed a transplant. Bone marrow contains stem cells that eventually differentiate into the three basic types of blood cells: red blood cells, platelets, and—critical to the immune system—white blood cells. The fact that Brown had both leukemia and HIV isn’t pure happenstance; HIV, which infects white blood cells and eventually causes AIDS, has been linked to the development of blood cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma.

Brown was treated with two bone marrow transplants, aggressive chemotherapy, and total body irradiation, a harsh treatment that landed him in a medically induced coma and nearly killed him. But after surviving his treatment, Brown found that both his leukemia and HIV were gone.

Dr. Steven Deeks, who treated Brown, told the New York Times, “He was really beaten up by the whole procedure. […] And so we’ve always wondered whether all that conditioning, a massive amount of destruction to his immune system, explained why Timothy was cured but no one else.”

Despite repeated attempts at reproducing the treatment, Brown had been the sole person to be cured of HIV until recently. Twelve years later, “the London patient” was cured of HIV as a result of a similar procedure. And now there’s news of a third, “the Düsseldorf patient,” who also appears to have been cured of HIV.

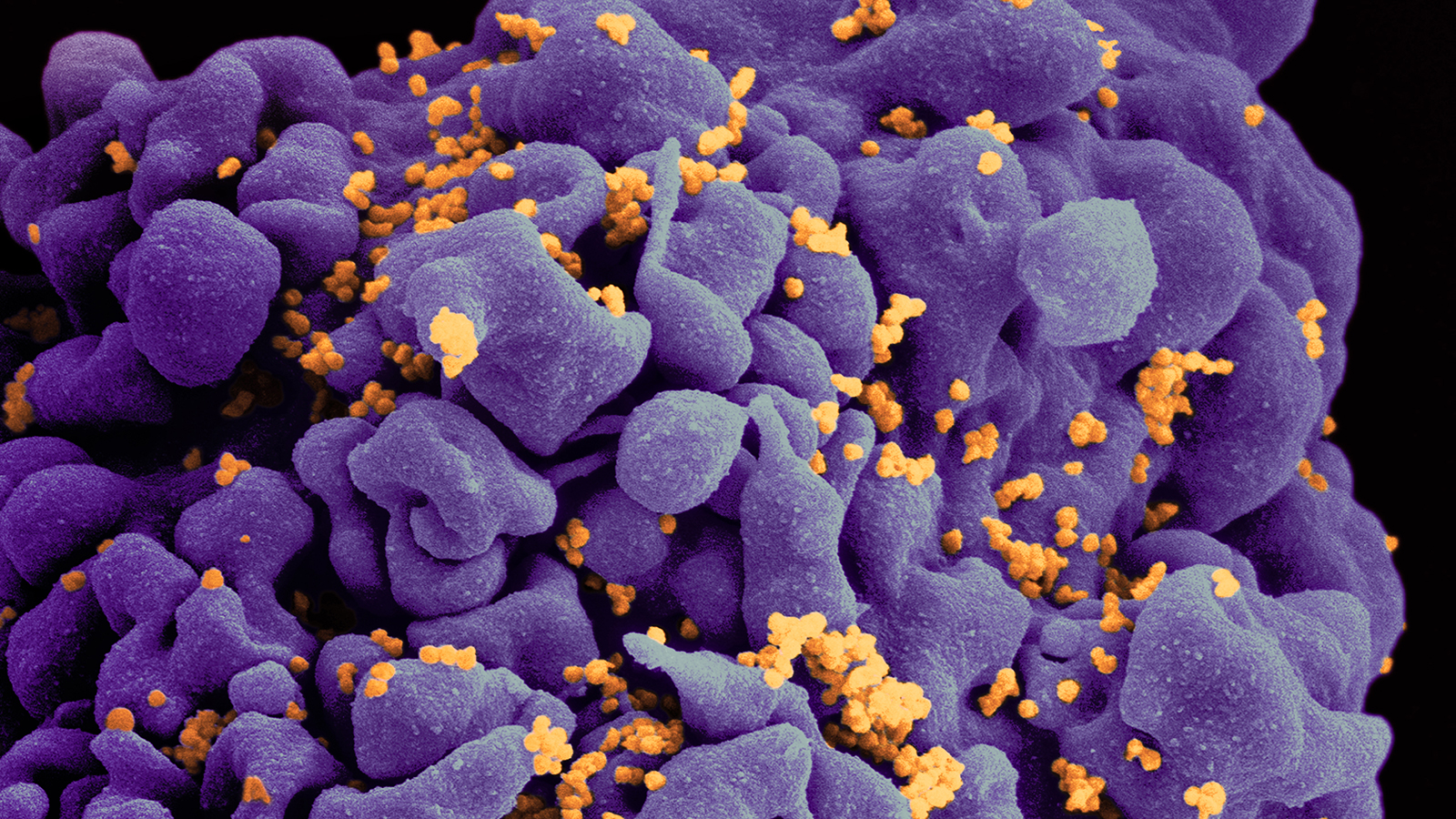

A scanning electron microscope image of HIV. The virus, colored in green, can be seen budding from the surface of a lymphocyte. Image source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Finding the right cure

Part of the challenge of recreating Brown’s success was identifying which factor of his treatment cured his HIV. The successful treatment of the London and Düsseldorf patients seem to suggest that the key lies in a genetic mutation called CCR5delta32.

Brown, the London patient, and the Düsseldorf patient all had some form of blood cancer — which, as mentioned earlier, are particularly common in people with HIV. All of them had bone marrow transplants in order to treat their cancers, and all of their transplants came from donors with a mutated CCR5 gene.

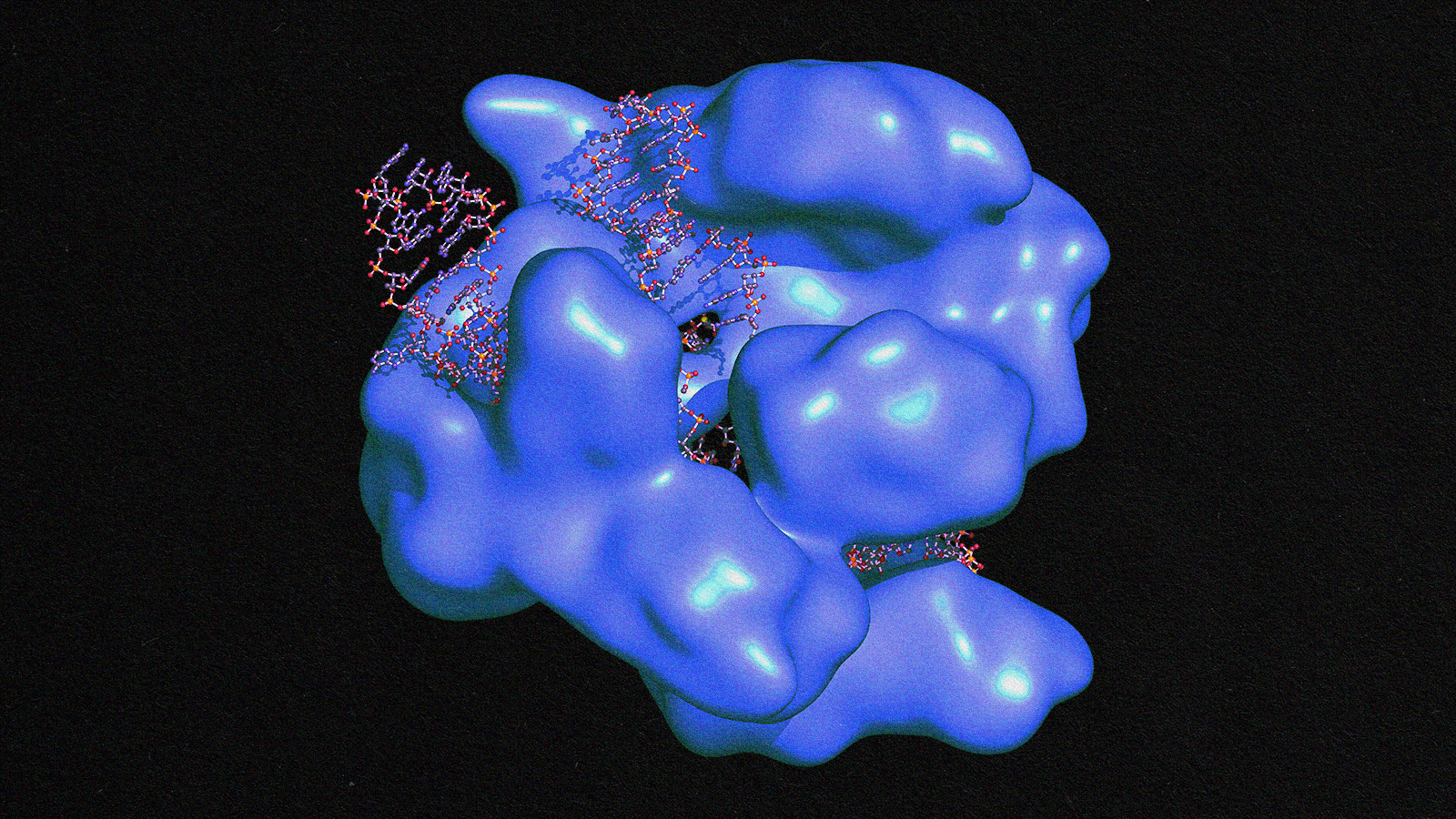

This gene produces the CCR5 protein, which is dispersed on the surface of white blood cells. HIV latches onto this protein and uses it to infect white blood cells, and if the virus manages to do so enough times, it causes AIDS. But the CCR5delta32 mutation renders this protein nonfunctional, essentially deleting HIV’s entry into white blood cells.

After receiving this rare bone marrow transplant, the London patient stayed on their HIV medication for nearly a year and a half before they were declared — for all intents and purposes — cured of HIV. The Düsseldorf patient stayed on their medication for only three-and-a-half months. In both patients, all that remains of the HIV viruses are broken bits of DNA that can no longer replicate.

Both patients were registered with IciStem, an international collaboration investigating how to cure HIV through stem cell transplants. IciStem has identified more than 22,000 donors with the rare CCR5delta32 mutation, which is most commonly found in caucasians (about 1 percent of them). It’s possible that more good news on this treatment is on the way as well: 36 other patients registered with IciStem have received these transplants, though its too early to definitively say whether they’ve been cured or not.

Good news and bad

It’s important to remember, however, that this treatment is still in its early stages. “To be clear, this is not an option yet for people with HIV, even in very rich countries, but it is a major step forward,” says Professor Francois Venter of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute. “This is incredibly exciting, as it furthers our understanding of the complex immunology of HIV and should get us closer to a cure.”

Part of the problem is that bone marrow transplants are extremely risky, which is why they’re reserved for individuals with life-threatening blood cancers. Transplants like these are at high risk for causing graft-versus-host disease. Because the job of white blood cells is to attack foreign cells, like those from a virus, donated white blood cells from a bone marrow transplant can begin attacking the host’s body. This is part of the reason why Brown came so close to death after his initial treatment.

Furthermore, another strain of HIV can enter cells without the CCR5 protein. This strain, called X4, uses the CXCR4 protein instead. Patients can harbor both strains of HIV, which occurred in at least one patient who received a CCR5delta32 transplant. While the normal strain of HIV subsided in this patient, the X4 strain moved to take its place.

In the admittedly small number of successful cases so far, the treatment has eradicated the normal strain of HIV. The X4 strain, if present, can be kept at bay with regular HIV medication, such as the daily pill Brown takes as a precaution against the alternative strain.

Moreover, rather than use a treatment as aggressive as a bone marrow transplant, it may soon be possible to use gene therapy techniques to add the rare mutation directly to HIV patients’ genetic code. Along this vein, the Chinese scientist He Jiankui used CRISPR to modify the CCR5 protein in two children to make them resistant to HIV. It’s extremely difficult to anticipate the ramifications of genetic modification like this, and Jiankui’s lack of caution drew international criticism from the scientific community.

However, with more research, an approach like Jiankui’s may be the way forward for curing HIV.