Weather forecasts have radically improved. Have you noticed?

- Weather forecasts are vastly better than they used to be and are continuing to improve. A modern five-day forecast is as accurate as a one-day forecast in 1980.

- More extensive observations, much faster numerical prediction models, and vastly improved methods of assimilating observations into models led to the improvement.

- As more advanced weather satellites come online and faster supercomputers are used to crunch weather data, forecasting will grow even more accurate.

People routinely make snide jokes about the inaccuracy of weather forecasts. It’s a status quo that irks MIT Professor Emeritus Kerry A. Emanuel and Penn State Professors Richard Alley and Fuqing Zhang, because, as the trio of experts in atmospheric science and geoscience noted in a paper published in the journal Science in 2018, those jokesters “wouldn’t dream of planning an outdoor activity without first checking the weather forecast.”

Moreover, the forecasts they mock have drastically improved in accuracy over the past few decades and continue to do so.

The wisdom of the weatherman

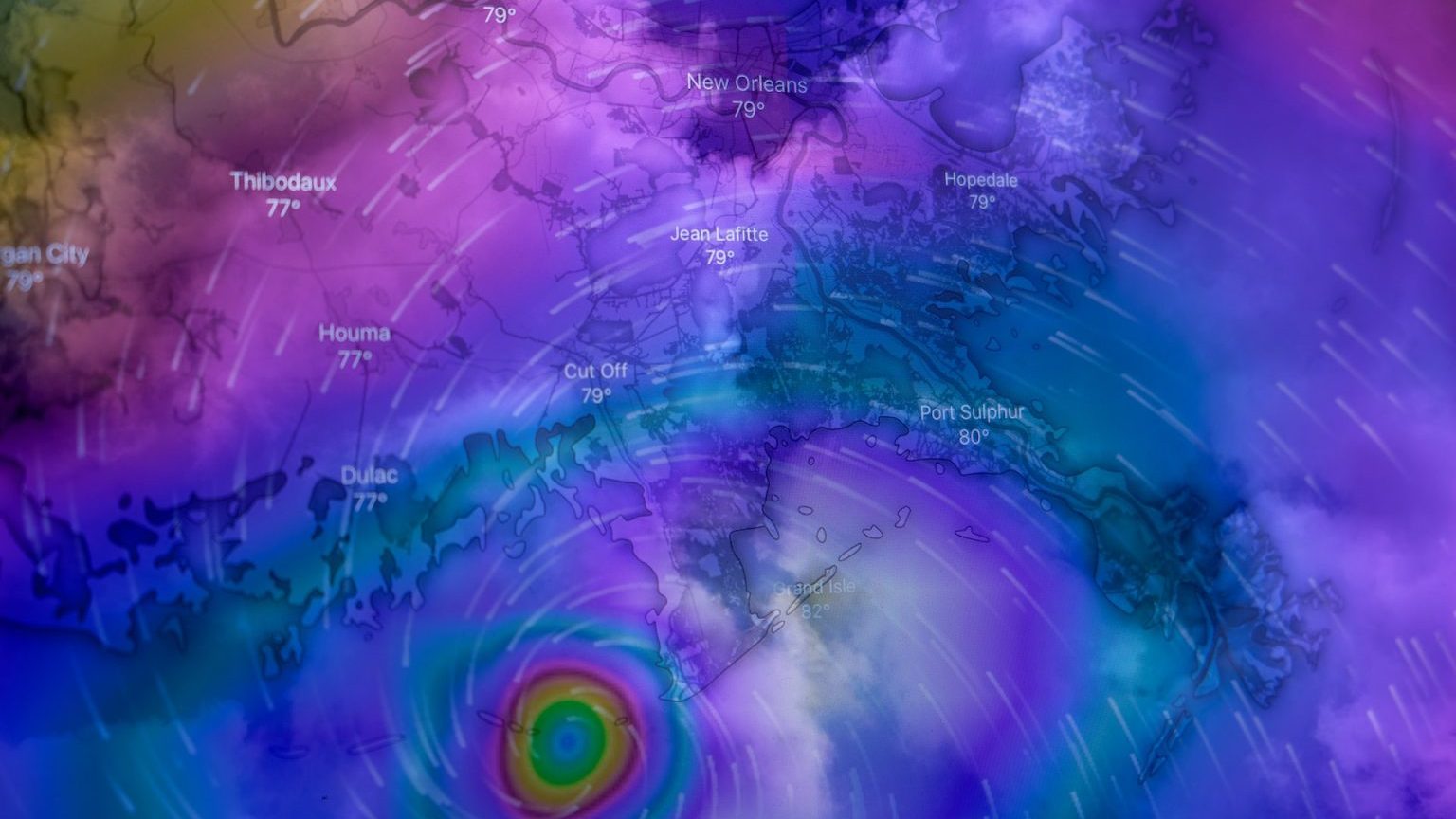

“Modern 72-hour predictions of hurricane tracks are more accurate than 24-hour forecasts just 40 years ago,” they wrote. “A modern five-day forecast is as accurate as a one-day forecast in 1980, and useful forecasts now reach 9-10 days into the future,” they added.

So though the weather prediction jokes continue, they are growing more and more unfounded every year.

Three key developments enabled weather forecasting’s giant leap forward, the authors said: “Better and more extensive observations, better and much faster numerical prediction models, and vastly improved methods of assimilating observations into models.” The improved observations have come from the proliferation of advanced weather satellites in Earth’s orbit, including the incredible lineup of Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites (GOES), operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), as well as the European Space Agency’s Meteosat satellites. Moreover, much faster computers have allowed for more advanced and detailed models.

The simple passing of time has also fed weather forecasting’s advance. Each day, week, month, and year, reams of data are collected and fed into prediction models, which are then adjusted accordingly, granting more and more precision as additional data arrives. The Earth is a system, and the more we monitor that system, the better we can foresee its future.

Still, there are hard limits to predicting the weather, the authors said. “The details of weather cannot be predicted accurately, even in principle, much beyond roughly two weeks.”

The good news, they added, is that there is still a lot of room for refinement within that time frame. Flood forecasts for coastal storms still need work, as do predictions of sea ice extent in the Arctic and the movements of smoke from increasingly frequent wildfires.

The future of meteorology

Meteorology also will have a massive role in a future renewable-centered power grid.

“As renewables come to play an increasing role in power systems, forecasting the availability of sun, wind, and river flow will take on increased importance, as will forecasts of energy demand, a large part of which is driven by weather,” the authors wrote.

But for weather prediction to keep improving, there needs to be a steady stream of monetary investment and human effort, they assert. Data collection needs to continue apace from the ground, sky, and space. Machine learning and neural networks need to be crafted and applied within earth sciences, particularly to learn more about intricate physical processes like cloud-aerosol interactions that still aren’t well understood. Governments also need to pay for supercomputing infrastructure to run increasingly advanced weather prediction models.

“With strategic investments, the future of weather forecasting and related environmental services is bright,” Emanuel, Alley, and Zhang concluded.