Fossils show ancient flying reptiles called pterosaurs likely had feathers

Yuan Zhang

- The specimens are of two small, flying reptiles discovered recently in China.

- In recent decades, multiple discoveries have led scientists to believe virtually all dinosaurs were covered in feathers.

- This recent discovery suggests that feathers were an adaptation that evolved before the dinosaurs, from a common ancestor.

During the 1990s and 2000s, paleontologists in China discovered a set of exceptionally well-preserved fossils that suggested theropods, a suborder of dinosaurs to which the velociraptor belonged, were covered in feathers. In 2014, paleontologists in Siberia came across another feather-covered dinosaur specimen. It wasn’t, however, a theropod.

These recent discoveries, along with past findings, have shown that at least four ancestrally distinct dinosaur groups had feathers. The implication is clear: It’s likely that almost all dinosaurs were covered in feathers. Now, two specimens of ancient reptiles recently discovered in China suggest that feathers evolved from a common ancestor to dinosaurs that dates back farther than scientists previously thought.

The fossils were of two anurognathids, which belonged to a group of flying reptiles called pterosaurs that existed during the Mesozoic era, some 228 to 66 million years ago. Pterosaurs, which came before the dinosaurs, are thought to be among the first vertebrates to evolve the ability to fly, and since the 19th century scientists have thought these creatures were likely covered in fur.

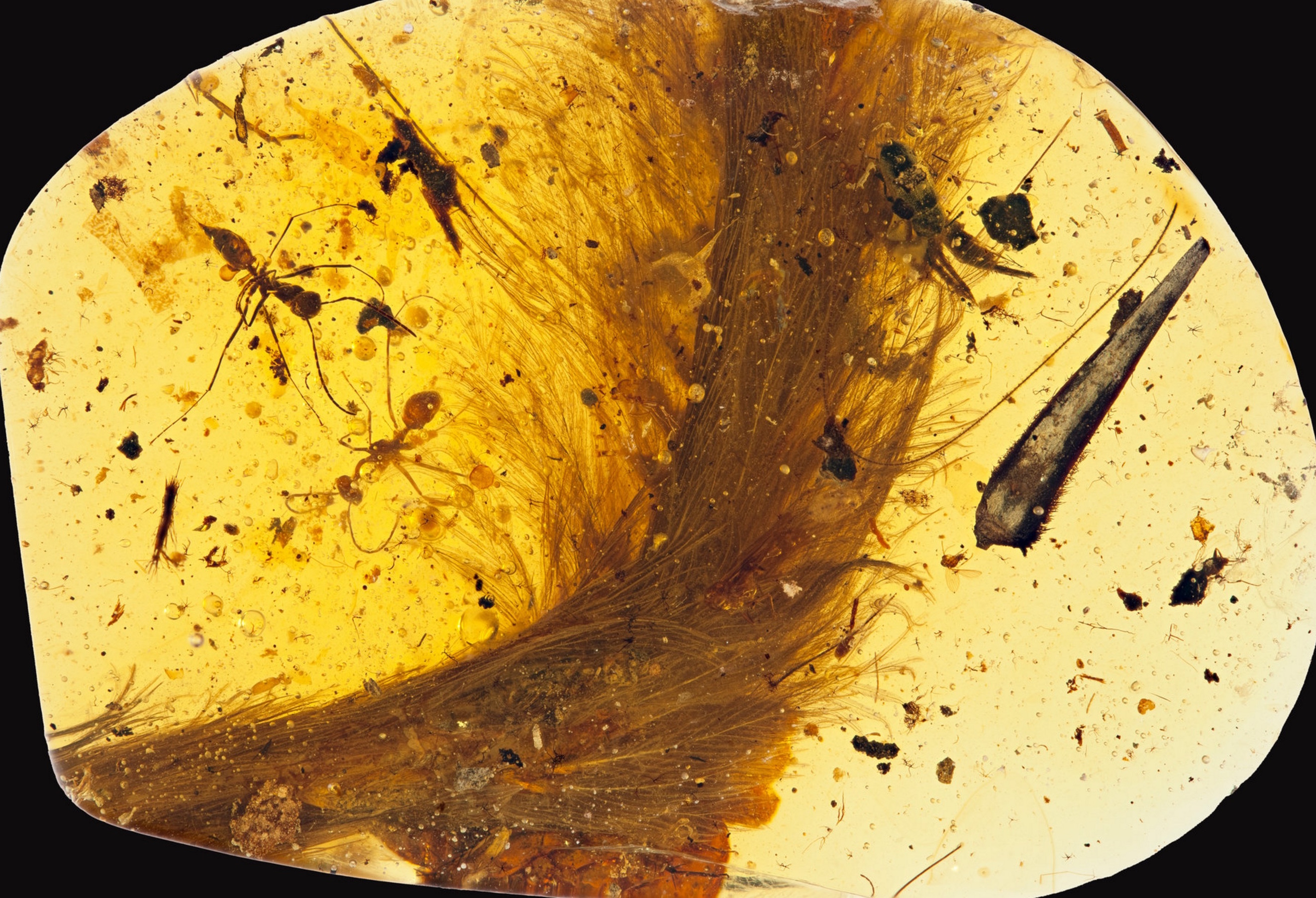

The researchers, who described their findings a study published December 17 in Nature, used four different methods to analyze the specimens, including traditional microscopes, scanning electron microscopes, fluorescence microscopy and laser-stimulated fluorescence imaging. Their results seemed to confirm the existence of hair-like filaments on pterosaurs and also, more surprisingly, three types of branched filaments similar to the kinds found on feathered dinosaurs. Although pterosaurs could fly, their feathers weren’t for flight but possibly for tactile sensing or camouflage.

As Gizmodo reports, the team also found in the feathers a cellular organelle called melanosomes, which synthesize melanin pigment, suggesting the reptiles had a ginger-brown color.

Pterosaur feathers

Baoyu Jiang, Michael Benton et al.

One of two possibilities

The study implies one of two things occurred millions of years ago: either ancestrally distinct groups of reptiles evolved feathers independently of one another, or they all share a feather-covered common ancestor that evolved feathers far earlier than previously thought. As scientists continue to discover that more groups of dinosaurs were covered in feathers, the common-ancestor theory becomes increasingly plausible.

“The most logical conclusion is that feathers go all the way back, beyond even dinosaurs, to a more distant ancestor,” paleontologist Steve Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh in the UK, who wasn’t involved in the study, told New Scientist. “The next step out on the family tree is crocodiles, so maybe, just maybe, a paleontologist will one day find a fossil croc with feathers.”

Paleontologist Armita Manafzadeh from Brown University, who wasn’t involved in the new study, told Gizmodothat the researchers’ analysis methods mark a “gold standard” for this kind of work.

“They used four complementary methods to analyze not only the shape but also the cellular and chemical composition of pycnofibers, giving us a much more thorough understanding of pterosaur integumentary [skin] structures than ever before,” Manafzadeh told Gizmodo. “This work goes to show us that synthesizing different methods can help us extract previously inaccessible data from fossils—and also that we still have a lot left to learn about pterosaurs,” she said.