To know the history of mammals is to know ourselves

- The death of the dinosaurs allowed mammals to become ascendant. But the history of mammals stretches far deeper than that. The first mammals go back about 325 million years, when the ancestral mammal lineage split from the reptile line.

- We’re learning more about the history of mammals at breathtaking speed. More mammal fossils are being found than ever before, and we can study them with an array of technologies.

- The history of mammals is our history, and by studying our ancestors, we can understand the deepest nature of ourselves.

Excerpted from the book THE RISE AND REIGN OF THE MAMMALS: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us by Steve Brusatte. Copyright © 2022 by Stephen (Steve) Brusatte. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

For the first time in years, the sun broke through the darkness. There was still a whiff of smoke wafting from the gray clouds, which blanketed the ground in shadow. Down below, the land was wrecked. It was all dirt and mud, a wasteland absent any greenery or color whatsoever. Silence hung in the wind, punctured only by the churn of a river, its currents clogged with sticks and stones and the residue of decay.

The skeleton of a beast lay upon the riverbank. Its flesh and sinew were long gone, its bones a moldy beige. Its jaws were agape in a scream, its teeth busted and scattered in front of its face. Each one the size of a banana, with the sharp edges of a knife, the murder weapons this monster had used to dismember and crush the bones of its prey.

It was, once, a Tyrannosaurus rex, the tyrant lizard, the King of the Dinosaurs, the oppressor of a continent. Now its entire species was no more. And little else seemed to be alive.

Then, from somewhere within the behemoth, a soft sound. A clicking chatter, a flutter of footsteps. A tiny nose poked out between a couple of T. rex ribs, haltingly, as if afraid to go any farther. Its whiskers trembled, in expectation of danger, but it found none.

Time to come out of hiding. It leapt upward, into the light, and scurried onto the bones.

Clothed in fur, with bulging eyes and a snout full of teeth that looked like mountain peaks and a whiplash tail, this critter couldn’t have been more different than a T. rex.

It paused for a moment to scratch the hair on its neck, turned its ear to the air, and scampered forward on all fours. Hands and feet planted firmly underneath its body, it moved fast, with purpose. Up the rib, across the backbone, and onto the dinosaur’s skull.

There, on the side of the head, where the eye of this T. rex once glared at herds of Triceratops, the furball stopped. It looked back in the direction of the rib cage, and let out a high-pitched squeak. From the bowels of the beast, out bounded a dozen smaller furballs. They raced toward their mother, and latched onto her belly, lapping up a breakfast of milk as they experienced their first minutes aboveground.

As she nursed her babies, the mother stared into the sunlight. The world now belonged to her, and her family. The Age of Dinosaurs was over, put to rest with the fiery destruction of an asteroid and a long, dark, global nuclear winter. Now the Earth was healing. The Age of Mammals had begun.

Some 66 million years later, more or less, another mammal stood in the same spot, swinging a pickaxe. Sarah Shelley was my first PhD student after I started my job as a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. We were in New Mexico, on a fossil hunt, searching for the bones and teeth and skeletons that would help us understand how mammals survived the asteroid, outlasted the dinosaurs, and made the world their own, becoming the furry animals that we know, love, and sometimes fear today.

Mammals are the most charismatic and beloved creatures on the planet — with all due respect to reptiles and birds and the other eight-million-plus animal species that are not mammals. Perhaps this is because many mammals are simply cute and fluffy, but in part, I think it’s because, on a deeper level, we can relate to them, and see ourselves in them. The cheetahs and gazelles locked in chase on the television screen, as David Attenborough’s dulcet tones narrate the drama. The mother otter playing with her pups on the cover of a nature magazine. The elephants and hippos that make every child beg their parents to take them to the zoo, and the endangered pandas and rhinos that pull at our heartstrings when so many other appeals for charity might annoy us. The foxes and squirrels that tolerate our cities, the deer that encroach on our suburbs. Whales with bodies longer than basketball courts, emerging from the abyss to spray blowhole geysers several stories into the sky. Vampire bats that literally drink blood, lions and tigers that make our hair stand on end. Our cuddly pets, of the feline or canine or sometimes more exotic variety. For many of us, our food — beef burgers, pork sausages, lamb chops. And, of course, us. We are mammals, in the same way that a bear or a mouse is.

As a porcupine shaded itself from the New Mexico afternoon in the nook of a cottonwood, and a colony of prairie dogs chirped in the distance, Sarah brandished her pickaxe. Each strike into the rock released a haze of foul, sulfur-smelling dust. Each time she would wait for the dust to clear, to see if anything interesting had loosened from the Earth. For at least an hour, each strike brought only more rock. Until, with one thwack, something with a shape, a different texture, a different color poked out. She knelt down to take a look. And then hollered a victory cheer so loud, and so happily profane, that I can’t repeat it here.

Sarah had found a fossil, her first major discovery as a student. I rushed over to see her prize, and she handed me a set of jaws, fused together at the tip. The teeth were coated in gypsum, and as they sparkled in the desert sun, I could see that there were sharp canines near the front and big, grinding molars at the back. Mammal! And not just any mammal, but one of the very species that assumed the crown from the dinosaurs.

We exchanged high fives, and got back to work.

Sarah’s jaws belonged to a species called Pantolambda, and it was big, about the size of a Shetland pony. It lived just a couple million years after the dinosaur extinction, generations after that little mother peered out from the T. rex rib cage, in my fictional but credible story. Already, Pantolambda was considerably larger than any mammal that ever saw a T. rex or Brontosaurus. Some of those meek creatures — none bigger than a badger — endured the asteroid, by virtue of their smallness and adaptability, and suddenly found themselves in a dinosaur-free world. They grew in stature, and migrated, and diversified, and soon began forming complex ecosystems, replacing the dinosaurs — which had ruled the Earth for over 100 million years.

This particular Pantolambda lived in a jungle, on the edge of a swamp (hence the nasty odor of its entombing rocks). It was the largest herbivore of this environment. As it waded into the cooling waters after a lunch of leaves and beans, it would have seen or heard an abundance of other mammals. Overhead, kitty-size acrobats negotiated the tree branches with their grasping hands. At the swamp’s edge, mutts with gargoyle faces burrowed into the mud, their claws seeking roots and tubers packed with nutrition. In the patchier parts of the forest, daintier ballerinas raced through the meadows on their hoofed toes. All the while, camouflaged in the thickest subtropical weeds of this Paleocene-aged jungle, a terror lurked: the apex predators, built like a stocky dog, with flesh-slicing teeth.

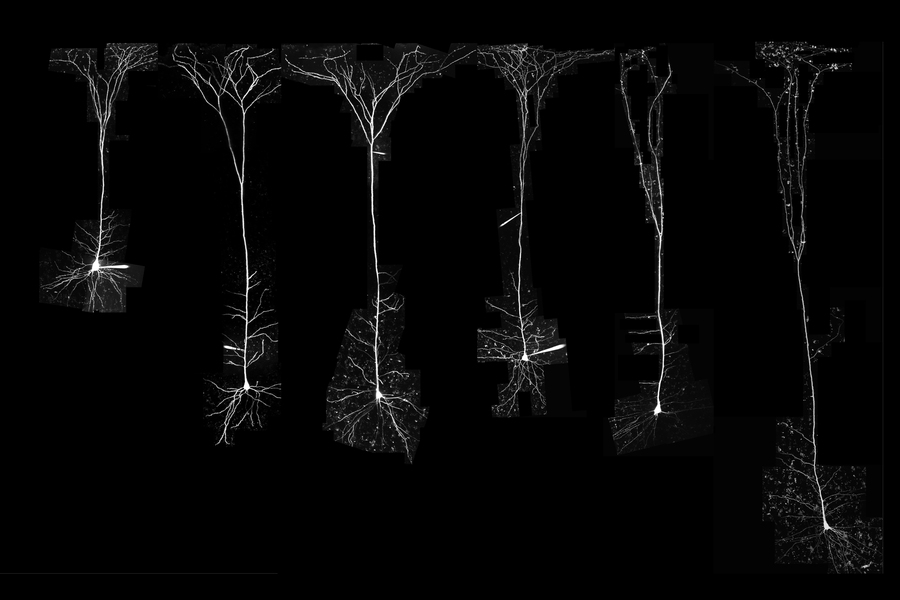

The death of the dinosaurs allowed these mammals — in ancient New Mexico and all around the world — to become ascendant. But mammals have a much deeper history. They — or rather, we — actually originated around the same time as the dinosaurs, over 200 million years ago, when all land was gathered together as one supercontinent, scorched by vast deserts. Those first mammals had an even deeper legacy, tracing back to about 325 million years ago, to a humid realm of coal swamps, when the ancestral mammal lineage split from the reptile line on the great family tree of life. Over these immense stretches of geological time, mammals developed their trademark features: hair, keen senses of smell and hearing, big brains and sharp intelligence, fast growth and warm-blooded metabolism, a distinctive lineup of teeth (canines, incisors, premolars, molars), mammary glands that mothers use to nourish their babies with milk.

From this long and rich evolutionary history came today’s mammals. Right now, there are over six thousand mammal species sharing our world, our closest cousins among the millions of species that have ever lived. All modern-day mammals belong to one of three groups: the egg-laying monotremes like the platypus, marsupials like kangaroos and koalas that raise their tiny babies in pouches, and placentals like us, which give birth to well-developed young. These three types of mammals, though, are simply the few survivors of a once-verdant family tree, which has been pruned by time and mass extinctions.

At various points in the past, there have been legions of saber-toothed carnivores (not only the famous tigers, but also marsupials that turned their canines into spears), dire wolves, giant woolly elephants, and deer with ridiculously enormous antlers. There were supersized rhinos that lacked horns but sported long necks to guzzle leaves high in the treetops to sustain their nearly twenty-ton girth—mammals mimicking Brontosaurus, setting the record for largest hairy beasts to ever live on land. Many of these fossil mammals are familiar: they are icons of prehistory, stars of animated movies, and exhibits at any reputable natural history museum.

But even more fascinating are some of the extinct mammals that have never quite made it into pop culture stardom. There were once wee mammals that glided over the heads of dinosaurs and others that ate baby dinosaurs for breakfast, armadillos the size of Volkswagens, sloths so tall they could dunk a basketball, and “thunder beasts” with three-foot-long battering-ram horns. There were oddballs called chalicotheres that looked like an unholy horse-gorilla hybrid, which walked on their knuckles and pulled down tree branches with their stretched claws. Before it docked with North America, South America was an island continent for tens of millions of years, and hosted a whole family of wacky hoofed species whose Frankenstein mashup of anatomical features flummoxed Charles Darwin — and whose true relationships to other mammals has only just been revealed by the shocking discovery of ancient DNA. Elephants were once the size of miniature poodles, camels and horses and rhinos once galloped across an American savanna, and whales once had legs and could walk.

Clearly, the history of mammals is far bigger than the mammals we can see today, and it’s about so much more than our own human origins and migrations over the last few million years. All of these fantastic mammals I’ve just mentioned, you’ll meet in these pages.

I started my scientific career by studying dinosaurs. Growing up in the midwestern United States, it was T. rex that fascinated me most, and I went to college and did a PhD and carved out a niche as a dinosaur specialist. A few years ago, I told the story of dinosaur evolution, from their humble origins to apocalyptic ex-tinction, in my book The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs. I’ll always love dinosaurs, and will continue to study them. But since I moved to Edinburgh and became a professor, I’ve started to drift. Perhaps it’s logical: having studied the dinosaur extinction, I’ve become obsessed with what happened afterward. I’ve become obsessed with mammals.

Sometimes people ask me why. Children everywhere dream of growing up and digging up dinosaurs, so why do anything else? And why mammals? My retort is simple: dinosaurs are awesome, but they are not us. The history of mammals is our history, and by studying our ancestors, we can understand the deepest nature of ourselves. Why we look the way we do, grow the way we do, raise our babies the way we do, why we have back pain and need expensive dental work if we chip a tooth, why we are able to contemplate the world around us, and affect it so.

And if that’s not enough, consider this. Some dinosaurs were huge, as big as Boeing 737 airplanes. The biggest mammals — blue whales and kin — are even larger. Imagine a world where mammals were extinct, and all we had were their fossil bones. No doubt they would be as famous, as iconic, as dinosaurs.

We’re learning more about the history of mammals at breathtaking speed. More mammal fossils are being found than ever before, and we can study them with an array of technologies — CAT scanners, high-powered microscopes, computer animation soft-ware — to reveal what they were like as living, breathing, moving, feeding, reproducing, evolving animals. We can even get DNA from some mammal fossils — like those strange South American mammals that infatuated Darwin — which like a paternity test tells us how they are related to modern species. The field of mammal paleontology was founded by Victorian men, but is now increasingly diverse, and international. I’ve been privileged to have mentors who welcomed me — just another dinosaur guy — into their territory of mammal research, and now I find my greatest joy in mentoring the next generation, like Sarah Shelley (whose illustrations grace these pages!), and many other excellent students who will continue to write mammal history with their discoveries.

In this book, I will tell the story of mammal evolution, as we know it now. Roughly the first half of the book covers the early stages of the mammal lineage, from the time they split from the reptiles until the extinction of the dinosaurs. This was when mammals acquired nearly all of their signatures — hair, mammary glands, and so on — and morphed, piece by piece, from an ancestor that looked like a lizard into something we would recognize as a mammal. The book’s second part lays out what happened after the dinosaurs died: how mammals seized the opportunity and became dominant, adapted to constantly changing climates, rode along on drifting continents, and developed into the incredible richness of species today: runners, diggers, flyers, swimmers, and big-brained book readers. In telling the tale of mammals, I want to convey how we’ve pieced together this story using fossil clues, and give you a sense of what it’s like to be a paleontologist. I’ll introduce you to my mentors, my students, and the people who have inspired me, and whose discoveries have provided the evidence that allows me to chronicle the narrative of mammalhood.

This book does not focus obsessively on humans; there are plenty of others that do. I will discuss human origins: how we emerged from primate antecedents, reared up on two legs, inflated our brains, and colonized the world—after living alongside many other early human species. But I’ll do so in one chapter, and give humans about the same attention as horses and whales and elephants. After all, we are but one of many amazing feats of mammalian evolution.

Our story is one that needs to be told, however, because although we’re only a single mammalian species and we’ve only been around for a fraction of mammalian history, we are impacting the planet like no mammal before. Our phenomenal success in building cities and growing crops and connecting the globe with highways and flight routes is having an adverse effect on our closest kin. More than 350 mammals have gone extinct since Homo sapiens came out of the forests and swept across the world, and many species are at high risk of extinction today (think tigers, pandas, black rhinos, blue whales). If things continue at the current pace, half of all mammals might succumb to the same fate as woolly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers: dead and gone, with only ghostly fossils to remind us of their majesty.

Mammals are at a crossroads, at the most precarious point in their — our — history since they — we — stared down the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. And what a history it has been. During our long evolutionary run, there have been times when mammals cowered in the shadows and times when they were dominant. Periods when they flourished and others when they were knocked back, and nearly knocked out completely, by mass extinctions. Eras when they were held in check by dinosaurs and eras when they were the ones doing the checking; times when none were bigger than a mouse and times when they were the biggest things that ever lived on Earth; times they weathered heat spikes and times they faced mile-thick glaciers, during the Ice Age. Times when they could occupy only the lower rungs of the food chain, and times when some of them — us — got conscious and became able to shape the entire Earth, in good and bad.

All of this history laid the foundation for today’s world, for us, and our future.