Confirmed: Some dinosaurs did nest in colonies

Image source: Noiel / Shutterstock

- Normal geological evidence isn’t precise enough to confirm paleontologists’ suspicions.

- The new fossils find is covered by a fine veneer of red sand deposited in a single season.

- Scientists can infer whose eggs they were.

Paleontologists suspected that some dinosaurs nested in colonies, but it was impossible to know for sure. Yes, they’d often found what appeared to be groups of fossilized eggs. But did these egg “clutches” date from the same time, or had they gradually accumulated in a popular nesting area?

An unusual layer of sediment recently found in the Gobi desert appears to finally answer this question: At least one group of dinosaurs definitely nested and protected their clutches as a colony. A report of the find was published Jul 15 in Geology.

Why paleontologist have been wondering

Crocodiles lay eggs together in nests that they guard and protect as a colony. There are also a variety of modern birds that do this: seabirds such as auks and albatrosses, wetland birds like herons, and even some blackbirds and swallows. As descendants of dinosaurs, experts have wondered how far back this goes. Since the first dinosaur eggs were unearthed in France in 1859, paleontologists have been finding them in hundreds of locations around the world, and in 1978, the first evidence of a nesting colony was discovered in western Montana. Such clutches contain anywhere from 3 to 30 eggs.

Dating of such fossils is typically imprecise, however. A layer of rock covering a find may take millions of years to lay down, and can only suggest approximate ages of individual fossils. Though radiocarbon dating using Carbon-12 isotopes has a margin of error of just decades, that’s still not quite close enough to establish that the eggs were actually contemporaneous.

The Gobi desert is the site of countless dinosaur fossils

Image source: Galyna Andrushko / Shutterstock

The thin red line

It took some extraordinary good luck to finally solve the riddle. In 2015, a group of paleontologist including some from Canada’s Royal Tyrrell Museum and the University of Calgary came across a large deposit of dinosaur eggs in China’s southeast Gobi Desert, in the Javkhlant formation. There were 15 nests and over 50 eggs about 80 million years old in a 286 square-meter formation.

What made the find so unusual, and ultimately dispositive, was the thin veneer of red rock, likely deposited in a single breeding season, that covered all of the eggs. It’s believed to be sand deposited by flooding from a nearby river. “Because everything is relatively undisturbed, it likely wasn’t a massive flood,” says François Therrien. Adds Darla Zelenitsky, another co-author, “Geologically, I don’t think we could’ve asked for a better site.” Equally compelling, some 60 percent of the eggs had already hatched and had the red sand inside them.

This “was a demonstration that all of these clutches were actually a true dinosaur colony and that all those dinosaurs built their nests in the same area at the same time,” asserts Therrien.

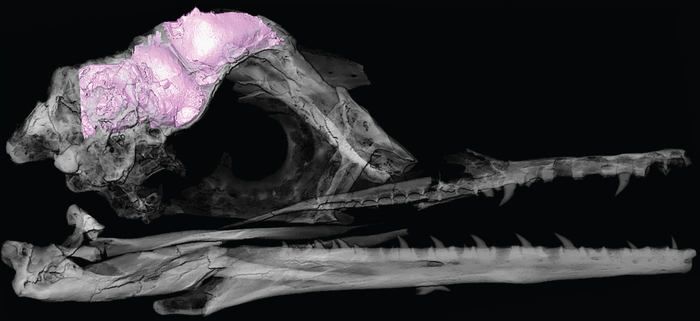

Whose eggs were they?

The find also offered up some insights into who these eggs belonged to. The texture and thickness of the eggs suggests their parents were non-avian theropods, a group that includes velociraptors. Not that these particular theropods were necessarily so fleet of foot.

“These animals were relatively big,” Therrien tells CBC News, “They were around seven to nine meters in length, so way too big to fly. And they would have been covered with feathers, but very primitive types of feathers… hairy and light. They would not have had wings and would have been unable to fly.” Such dinosaurs had, he adds, “a long neck, small head, but they have very, very large hands and very, very long claws on their four limbs,” likely for defense.

The scientists were also able to infer something about the dinosaurs’ parental behavior by comparing the rate of successful hatches to modern animals such as crocodiles and birds that guard their eggs. The survival rate strongly suggests that the colony protected their progeny throughout the incubation and hatching process, rather than abandoning them. Says Therrien, “If we compare that to modern animals, we see a very high hatching success like that around 60 percent among species where one or several parents guard in their colony. Basically, if the adults leave — abandoned the nest — we have a much lower hatching success because the eggs either get trampled or get predated upon.”

“Sometimes you can extract a fascinating and detailed story about the ecology and behavior of these animals simply by looking at the rocks themselves,” he notes.