Why 21st Century Shakespeare Still Looks Like 19th Century Shakespeare

Our century now lays claim to our own Shakespeare—a 21st century Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s on Twitter, on Facebook, and even on Second Life, just like any modern producer and consumer of social media. But as much as we want a shiny, new Shakespeare just like us, 21st century Shakespeare looks a lot like 19th century Shakespeare. No matter how we want to shake the Romantics, we’re all still their children. Take away the Tweets and the Facebook updates, and our Shakespeare resembles their Shakespeare, especially in how artists saw him and depicted his creations.

Shakespeare, of course, captured the imaginations of generations starting with his own and every one that followed. When the Romantic generation emerged in the late 18th and early 19th century, a new Shakespeare was born. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1798 co-authored collection of poems Lyrical Ballads set the tone for the movement in England. Wordsworth injected fragments of Shakespeare into his works, perhaps most memorably the “Sleep No More” passage of Book 10 of The Prelude that echoed Shakespeare’s Macbeth. John Keats carried a portrait of Shakespeare wherever he travelled and hung it above his desk for inspiration whenever he wrote. But it was Coleridge who became the biggest Romantic Shakespearean.

Coleridge delivered lectures on Shakespeare’s plays, especially Hamlet, that became the foundation for Shakespearean literary criticism ever since. In the 20th century, however, T.S. Eliot took issue with the Romantic Shakespeare Coleridge conceived. In the 1922 essay “Hamlet and His Problems,” Eliot complained that Romantic critics of Shakespeare “often find in Hamlet a vicarious existence for their own artistic realization. Such a mind had Goethe, who made of Hamlet a Werther; and such had Coleridge, who made of Hamlet a Coleridge.” This too powerful identification forged by these critics irked Eliot, who saw criticism’s “first business [being] to study a work of art.” What Goethe and Coleridge did, according to Eliot, was “the most misleading kind possible.” Eliot longed for the “good old days” of appreciation instead of appropriation. We’ve never returned to that golden age, at least for T.S., since.

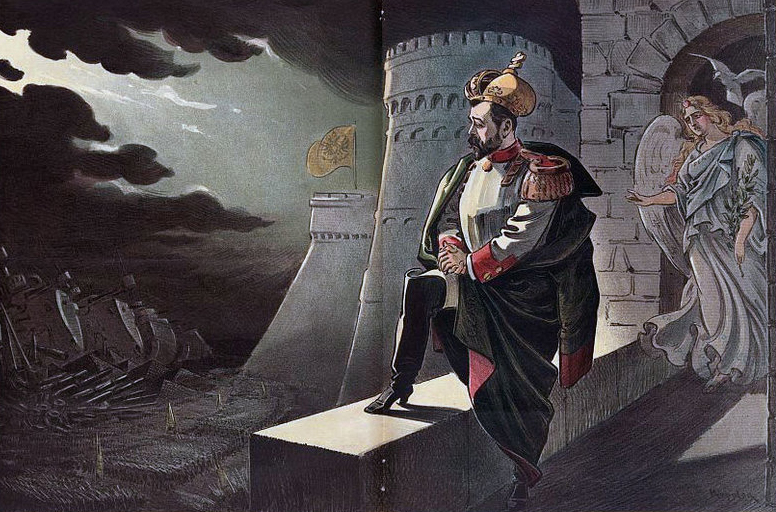

Visual artists followed suit. William Blake, the only Romantic poet to also paint, painted a Portrait of Shakespeare based on the First Folio portrait, which put a Romantic spin on the familiar face of the Bard. When Blake painted The Genius of Shakespeare, however, he escaped the surface reality of Shakespeare’s art and penetrated to its heart, or at least how Blake saw that heart beat. Perhaps Blake made of Shakespeare another Blake, to paraphrase Eliot on Coleridge, but that poetic and painterly license seems as natural to us today as it would have seemed alien to Blake’s contemporaries still coming to grips with Romanticism. Blake’s friend and fellow Romantic artist Henry Fuseli painted Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost (shown above in an engraved version by Robert Thew), which plunges the viewer into the drama of Shakespeare’s Danish play with proto-expressionist body language and passionate facial expressions. Publisher John Boydell actually created the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery to house and promote this new Romantic strain of Shakespearean-inspired art. Some holdovers from the previous generation of neoclassical art, such as James Northcote, contributed to Boydell’s gallery, but it was clear that Fuseli’s new look was taking hold of the public imagination.

We’ve never shaken the look of 19th century Shakespeare because we’ve never shaken the Romantic mindset. The Pre-Raphaelites continued the Bardmania of the Romantics, and maybe even amplified it. Even when the endless parade of modern art movements began rolling through the 20th century, each one either embraced Romanticism or ran from it. Either way, Romanticism drove them in some direction. The solipsism of 21st century Shakespeare, who tweets and acts like us, takes 19th century Romantic self-identification to an extreme that must have T.S. Eliot spinning in his grave. The next time your look into the mirror of Shakespeare to find yourself, remember that using the idea of Shakespeare as a mirror places you firmly in a tradition two centuries old.

[Image:Robert Thew after Henry Fuseli. Hamlet, Horatio, Marcellus and the Ghost. Published 29 September 1796. Stipple engraving on paper, 500 x 635 mm.]