Songs of Lament: Susan Philipsz wins The 2010 Turner Prize

Like the banshee of Irish and Scottish legend, Scottish artist Susan Philipsz keens songs of lamentation and loss that haunt those within hearing of the “sound sculptures” centered on her voice. For those unforgettable installations, Philipsz has won the 2010 Turner Prize, the most prestigious British contemporary art award and one of the biggest life-changing achievements an artist can realize today. Her win marks a strange milestone for The Turner Prize in that the intangible medium of sound has joined film, sculpture, and painting—the medium of choice for the prize’s namesake, J.M.W. Turner—as acceptable conduits for creativity. Some see crossing that barrier as going too far and raise their own hue and cry. But outside of the prize-awarding festivities, a different song of lamentation could be heard—the mourning over the impending death of the arts in England.

Dexter Dalwood, the bookies’ favorite to win (yes, the Brits bet on this kind of stuff) and the member of the shortlist working closest to what can be called a traditional style, will get a £5,000 award, as will fellow runners-up hybrid painter-sculptor Angela de la Cruz and filmmakers The Otolith Group. Philipsz takes home £25,000 and the claim to fame and/or infamy that comes from joining the ranks of previous winners Damien Hirst (1995), Chris Ofili (1998), and Richard Wright (2009). Traditionalists favored Dalwood’s modern take on history painting, but the twisty path of Turner history bent in Philipsz’s direction instead. “Dexter Dalwood’s paintings seemed to me too brittle, too clever and contrived to win,” writes British art critic Adrian Serle. Serle praises Philipsz’s win as comparable to Tomma Abts’ 2006 Turner . “In both cases I was impressed by the artists’ originality—not a word you hear much in contemporary art circles, their inventiveness, and the difficult yet accessible pleasures their art can give,” Serle reasons. Where some see sound as music and not Turner-worthy art, Serle sees an artist borrowing from another medium to create an installation just as many take from film, a once frowned-upon medium now commonly accepted in galleries and museums.

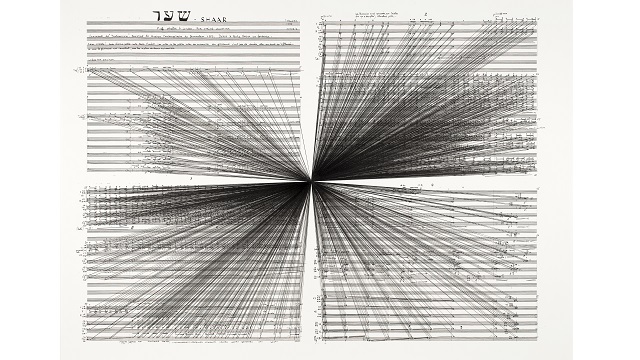

“I work with sound,” Philipsz explained in a BBC interview a few months ago, “but that sound is always installed in a particular context and that context with its architecture, lighting and ambient noises forms the entire experience of the artwork. It is a visual, aural and emotive landscape.” For those who claim that Philipsz’s art is purely immaterial and, therefore, not Turner-worthy art, the artist responds neatly that the sound is just part of the equation. The sense of place—literally the walls against which the sound echoes as much as the air and, often, water that carry the sound waves—makes up a good part of the effect, embodying her disembodied, recorded voice. (You can hear a clip of Philipsz’s voice singing “Lowlands,” a traditional Scottish lover’s lament for her lost sailor, beneath a bridge over the Clyde River [shown above] as part of an interview with Philipsz here.) For me, the true question of any Turner Prize is whether Turner himself would approve. Obviously, that takes a bit of time-traveling mind reading, but I can easily imagine Turner, besodden with his own love of the sea, falling in love with the way Philipsz uses water to amplify the power of her keening voice, which mourns in the lyrics the loss of a man to a watery grave, but in the placement among the decaying infrastructure of London sounds a different lament for the lost glory of a major city and, perhaps, an entire era passing before our eyes.

Part of that mourning for a passing era found embodiment in the form of approximately 100 students from London’s art schools peacefully protesting the coalition government’s “austerity” budget slashing of funding for the arts and humanities in higher education. (The recent debate over allowing museums to sell off collections to survive financially, which I discussed earlier, stems from this same budget crunch.) Gill Addison, lecturer at the Chelsea College of Art, explained that the protests were “not in opposition to the Turner prize but about the fact that our arts and culture are in jeopardy… It’s about the future of the Turner prize. How can it continue without artists being trained?” How strong is a civilization if it allows its culture to crumble for the want of financial support? Philipsz herself had not problem sharing the spotlight with the protesting students. “My heart goes out to them,” the Turner recipient said in solidarity. “I really support them.” Perhaps Philipsz’s songs of lamentation and loss are the perfect emblem of the state of the arts in London, which are nearing funereal proportions. Like a banshee at an Irish wake, whose song serves both to mourn the dead and ensure that the departed is really gone, maybe the combination of Philipsz art and the presence of the art students—the future of art currently in jeopardy—will wake the masses to the need to save the dying arts before it is too late.

[Image: Susan Philipsz. Lowlands 2008/2010. Clyde Walkway, Glasgow. © The artist, courtesy Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art. Photo: Eoghan McTigue.]