Reorientation: The Orient Expressed at the Mississippi Museum of Art

“Disorientation is lost of the East,” novelist Salman Rushdie has written, reminding us of the original meaning of “Orient.” In The Orient Expressed: Japan’s Influence on Western Art, 1854-1918, which runs at the Mississippi Museum of Art through July 17, 2011, the curators hope to reorient us to the term Japonsime so that we can find the East, or more accurately the East of the 19th century West, lost over time. The sense of wonder over the new world of Japan suddenly opened up in 1854 is something we today could only experience if life were found on Mars. In the catalog and exhibition itself, Japan, currently reeling from disaster, reemerges as the rich land of culture and style so influential on Western art and design. It’s a reorientation course we in the West can’t do without.

Philippe Burty coined the term Japonisme in 1872, calling it a “new field of study—artistic, historical, and ethnographic.” As Elizabeth K. Mix stresses in her catalog essay, Europeans in the second half of the 19th century felt as if they had exhausted all the resources of their own traditions. When Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Japan in 1853 and essentially forced the Japanese to open their doors that had been closed for centuries, a whole new untapped source of tradition suddenly offered itself to European artists.

Petra ten-Doesschate Chu analyzes the trajectory of how Western artists approached Japanese ideas and imagery. She argues against “the artificial distinction made, in the modernist narrative, between chinoiserie and Japonisme, along the lines of ‘flirtation’ vs. ‘understanding,’ or superficial borrowing of exotic subject matter vs. thoughtful adoption of new formal characteristics.” ten-Doesschate Chu, whose The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth-Century Media Culture (which I reviewed here in 2007) deconstructed the standard story of Courbet’s self-promotion, similarly strips away the fairy tale of simple dalliance with Japan evolving into a mature, sensitive appropriation. Instead, “[t]hanks to travelogues and exhibitions,” ten-Doesschate Chu counters, “a new nineteenth-century fantasy of China replaced the old eighteenth-century one, without, however, completely erasing it.” Japonisme grew in influence and diversity, but the imaginary magic world of the East always lived at the core.

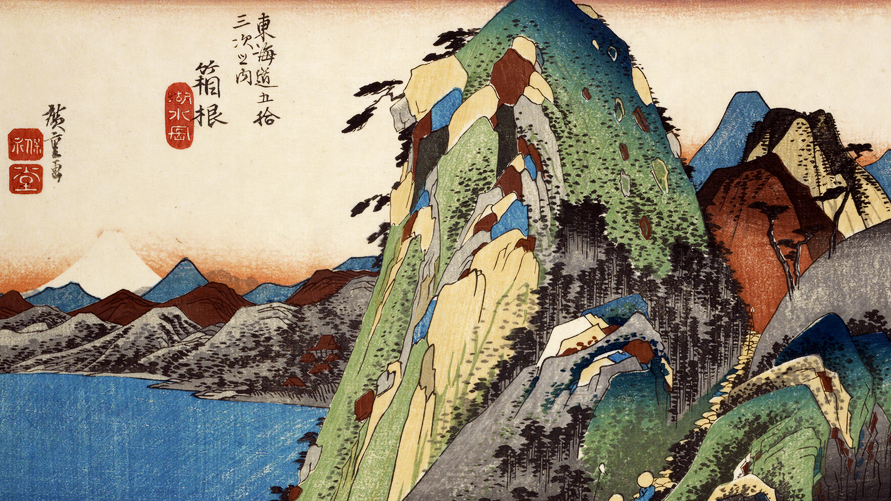

For many, that fantasy Japan meant both exoticism and eroticism. Sarah Sik delves into the sensuality of “gendered” Japonisme. Sik sees “the countless depictions of women—both Japanese and Western—immersed in Japanese settings” as “epitomiz[ing] the fantasy of the island nation as a ‘floating world’ of pleasure.” Even Claude Monet painted his wife in a kimono waving a Japanese fan, just one of the Western artists who put Western women in Oriental dress as a erotic code. Even as “innocent” an image as Paul Gauguin’s Still Life with Onions, Beetroots and a Japanese Print (shown above) can be seen as drenched in Japonisme-flavored sex. Gauguin usually channeled Tahiti as his place of primal urges, but in this painting the Japanese print and the spread of softly rounded vegetables team up to tell us what’s really on Gauguin’s mind.

Gauguin’s roommate, Vincent Van Gogh, shared in that same sex objectification of Japonisme. Mix uses Van Gogh as a representative case of appropriation of Japanese art based on what ten-Doesschate Chu would call a fantasy. Van Gogh never traveled to Japan. His understanding of Japanese culture came straight out of novels by the Goncourt brothers and Pierre Loti’s Madame Chrysantheme. Van Gogh traveled to Arles in the south of France hoping to find a kind of Japan in France. “Looking at nature under a brighter sky can give us a more accurate idea of the Japanese of feeling and drawing,” Vincent wrote in a letter of this period. In 1888, Van Gogh painted himself as a “bonze” or Japanese priest, or at least how Loti’s novel led him to believe such a bonze would appear. In 1887, Van Gogh painted three copies of Japanese prints (two by Hiroshige and one by Eisen) he titled Japonaiseries. “All three works… either depict or reference courtesans” based on Loti’s geishas, Mix writes, thus, “Van Gogh’s legendary troubles with ‘real’ women may have combined with a desire for a utopian version based on the common misunderstanding of geisha.” Even a soul as sensitive as Van Gogh’s couldn’t help but color the Japonisme he appropriated, helping dispel the myth of progress in cultural appropriation.

Mix follows her revelations about Van Gogh’s Japonisme with fascinating counterappropriations of Western art by Japanese artists such as filmmaker Akira Kurosawa and photographer Yasumasa Morimura. That back and forth of today’s small world of telecommunications is how the “orient” is truly expressed today, but reorienting ourselves to the days of Japonisme in the past helps us understand how to see Japan today and in the future. The Orient Expressed: Japan’s Influence on Western Art, 1854-1918 speaks of geishas, woodblock prints, and exotic dress, but what we may hear now are earthquakes, tsunamis, and nuclear reactors. Only by recognizing our fascination with the myth of Japan can we embrace the reality.

[Image:Paul Gauguin (French, 1848–1903), Still Life with Onions, Beetroots and a Japanese Print, 1889. oil on canvas. 16 x 20.5 in. Collection of Judy and Michael Steinhardt, New York, New York.]

[Many thanks to the Mississippi Museum of Art for providing me with the image above and press materials for the exhibition The Orient Expressed: Japan’s Influence on Western Art, 1854-1918, which runs through July 17, 2011. Many thanks also to the University of Washington Press for providing me with a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition.]