How much privacy are we willing to give up?

[cross-posted at the TechLearning blog]

I’ve been reading Everyware:

The dawning age of ubiquitous computing

by Adam Greenfield. It’s a

fascinating book and I’m learning a lot.

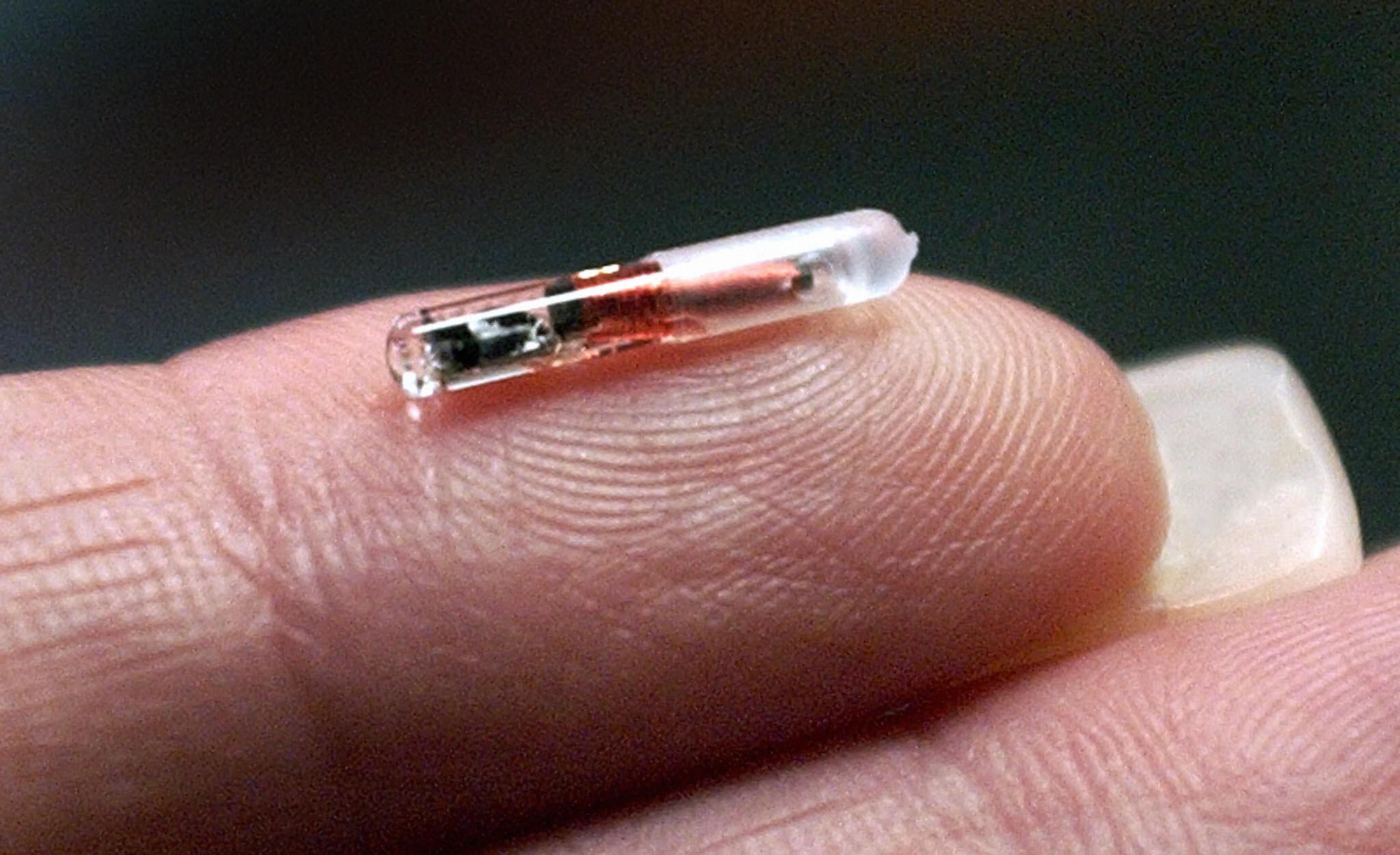

Greenfield’s essential premise is that in the foreseeable future sensors and

transmitters can and will be embedded into everyday objects, ranging from the

clothes on our body to the milk in our refrigerator to the blanket on our bed to

the picture frame on our wall. This essentially makes the things we use everyday

into quasi-digital devices. The rapid evolution, miniaturization, and

affordability of RFID chips, and their incorporation into various aspects of

life, is one example of this trend. The inclusion of GPS technologies in cars,

cell phones, and watches is another. So is some of the work currently being done

with mesh networks, smart

dust

, and the like. Once embedded, these sensors and transmitters will be

able to communicate with each other and with more complex digital technologies

like your home computer.

Why will sensors and transmitters be embedded into everyday things? Because,

as Greenfield notes, in the battle between convenience and privacy, most folks

are more than willing to give up some privacy for convenience. I saw this in

action quite clearly during my visit to the Microsoft

Home of the Future

in 2006. A few illustrative examples:

- Imagine that your kitchen counter can discern what you put on it (milk,

eggs, flour) and that a recipe appears on the counter surface informing you of

the various things that you can make with those ingredients.

has informed it that you’re running low on pancake mix.

because the motion sensors in Grandma’s apartment haven’t registered any

movement for the past six hours even though it’s mid-day.

sense the people who enter

and adjust the art, lighting, temperature, etc.

to reflect individual preferences.

in your eyeglasses that could register the identity of the person walking toward

you and quickly say into your ear her name and how you know her.

These are just a few of the many, many possibilities. Think medicine bottles

and backpacks, toilets and toys, floors and doors, and…

Greenfield believes that the arrival of ambient

informatics

is inevitable. The power and potential will be too

great for most people to refuse and, in many cases, the capabilities will be in

place before folks even have a chance to think too hard about it and/or make

objections. However, Greenfield also notes that we need to start thinking and

talking about whatever social, ethical, and other concerns we may have right

now. After these informatics are embedded and installed, it often will be too

late because there are logic rules that are built into the construction of the

sensors and transmitters. For example, maybe you don’t want your floor or front

door or toilet ‘spying’ on you but you do want your refrigerator to do so. You

need to think about that at the front end during the design and/or purchasing

stage, not after the fact.

There’s a lot more I could say on this, but I’ll close with a strong

recommendation that folks read Everyware.

It’s a very different way to think about digital technologies and yet I agree

with Greenfield that it will be our future. We need to start talking about this

aspect of ubiquitous computing and we need to ask

ourselves, “How much privacy are we willing to give

up?

“