Plato on what makes us tick & why math matters so much

This is the second diablog* with Rebecca Newberger Goldstein. RNG is a philosopher, novelist, certified MacArthur “genius,” winner of a National Humanities Medal, and likely the closest we can get to Plato being alive in our midst (see Plato at the Googleplex, which wonderfully images what would happen if Plato had to go on a contemporary book tour).

1. JB: Many know that Plato was besotted by math, but why on earth did he believe its beauty could “save us”?

2. RNG: I wouldn’t myself use the word “besotted,” which implies something irrational. Plato was always after a ‘something’ that was real and beautiful and that would have the power to overcome our irrationality and self-centeredness. Toward the end of his life, he identified that something with mathematics. He wasn’t optimistic about human nature. He saw us as almost—almost—incurably self-centered, with the vectors of our attention stubbornly pointing inward. He was looking for a means of turning them outward.

3. JB: Love that phrase “vectors of…attention”… very apt for our very selfie-absorbed times. Plato’s perception that rationality is rare contrasts sharply with today’s dominant and damaging “rational actor” model, which runs the logic that runs the world, while worsening self-centeredness, especially in certain “elite” circles.

4. RNG: Thinking in a narrow and amoral way about our own self-interest is, for Plato, almost the definition of irrationality. Our self-centeredness makes us not only stupid but nasty. We conjure up delusional images of the world that fit our biases that serve our self-aggrandizement, preferring this delusional nonsense to the study of reality itself. This is what makes us so stupid.

5. JB: It’s stupefying that many experts have only recently rediscovered many everywhere- evident “cognitive biases.” Ignoring them surely takes expert-level delusional nonsense (see Gary Becker’s “rational addiction”).

6. RNG: Being so single-mindedly devoted to the prospering of our own selves, we live in endless competition with each other. This is what makes us so nasty.

7. JB: Doesn’t our word idiot come from the Greek idiotes, which refers to those who live for private interests? Didn’t Plato consider that a pejorative term? I know you’ve called Plato’s writing a “morass of interpretive confusion,” but Isaiah Berlin claimed that there was “no trace…of genuine individualism” back then. And Aristotle felt that only “a beast or a god” (i.e., a superhuman or subhuman) could live without society.

8. RNG: The very force with which Plato opposed living for our private interests and pleasures—the great range of arguments he erected against unenlightened individualism—demonstrates how mistaken Isaiah Berlin was in denying the vitality of individualism in the ancient Greek world. Quoting Plato, Pericles, or Aristotle as if they’re interchangeable with any Timon, Dicaeus, or Hieronymus (as Isaiah Berlin does) is akin to quoting Peter Singer to speak for any Tom, Dick, or Harry’s attitude toward combating world poverty.

9. JB: Speaking of Pericles, he seemed to grasp that not all kinds of individualism are equally safe or self-absorbed. As he said in his celebrated Funeral Oration, which you quoted in your last book, “If the city is sound as a whole, it does more good to its private citizens than if it benefits them as individuals while faltering as a collective…. It does not matter whether a man prospers as an individual: If his country is destroyed, he is lost along with it.” He saw logical limits on survivable individualism.

10. RNG: We can get along if we become convinced that it’s in our self-interest, and we can learn to do so under the civilizing influence of the city, where it’s pretty obvious that we need to depend on one another for the sake of our own flourishing. But cooperation doesn’t come naturally to us, according to Plato, and, given the slightest strain, there’s that nastiness again. Stupid and nasty is our default. Plato is looking for something powerful to shift our default. He’s looking for us to fall in love with something greater than ourselves.

11. JB: Here evolution and anthropology can supply evidence. For 10,000 generations, our ancestors survived by cooperative hunting. (We’re the giraffes of non-kin cooperation.) This paleo-economics shaped our “moral sense,” i.e., our evolved social-rule processors. Perhaps Plato suffered a form of WEIRD (i.e., Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) bias, overgeneralizing the Greek love of agon (competition, from which, incidentally, we derive the word agony). Many cultures are sociocentric, and degrees of measured individualism vary widely (e.g. USA = 91, China = 20.)

12. RNG: Plato of course didn’t have the benefit of knowing modern evolutionary theory. But I think his response to you would be that we have evolved to cooperate with those whom we regard as of our own kind. Banding with our own tribe was essential for us as hunter-gatherers, just as it’s essential for many primates. But in any society that reaches the level of complexity of the Greek city-state, not to mention the modern nation-state and the global community, we will be dealing with others whom we judge to be not of our own kind. (I write this on the day after the Brexit vote.) The very mechanism that promotes cooperation with some members of our own species also promotes competition with others. We play on teams, cooperating with our teammates, competing with others.

13. JB: Agreed—a mix of cooperation and competiveness, and the related team dynamics, is crucial. (Teamwork has been called humanity’s “signature adaptation.”) But our team logic works differently from judging “our kind.” And I’d argue that the “Periclean pattern” applies in cases where individuals depend on teams or “survival vehicles.” At evolution’s lowest level, selfish genes cooperate with vehicle-mates (see here). If it’s essential to your own survival for X to survive, gaining at the expense of X can at some point become self-undermining (whether X is your team, tribe, city, nation, etc.).

14. RNG: I don’t believe that the genetic or cellular level provides the right level of analysis for understanding the kinds of reasons we humans provide in explaining and defending our decisions (and we are, distinctively on this planet, the reason-giving creatures). The cooperative behavior of genes and cells (obviously necessary for an organism to exist) gives us no grounds to believe that cooperation comes naturally to us. Quite the contrary, the genes “designed” us to put our own survival and flourishing first (as well as the survival and flourishing of those who carry similar genes to ours—so yes, of our own kind), so that replications of our genes would be carried into future generations. This is the core strategy of the genes, the driving force of evolution. But we don’t consult the genes when it comes to offering reasons for our behavior. That takes place at an entirely different level. We have evolved into reason-giving creatures, who hold each other accountable for both our beliefs and our actions, and it’s at this level, rather than the level of the genes, that we can be persuaded that it makes sense to cooperate more widely than is our natural inclination. But it requires persuasion. The constituents of our bodies don’t do it for us. If they did, we would be a far more agreeable species.

15. JB: Although our genes don’t automatically ensure that we’re agreeable teammates, their survival games are complicated by being deeply dependent on the survival of non-kin teammates. Different cultures configure our moral/team instincts differently, and I’d argue those that are more aligned with the logic of the “Pericles pattern,” are better equipped to survive longer. (Darwin believed this also.) By the way, the phrase “enlightened individualism” was coined by Tocqueville in the 1830s. One of the chapters of Democracy in America is titled “How the Americans Combat Individualism by the Principle of Self-Interest Rightly Understood .” Apparently, Tocqueville perceived that American Toms, Dicks, and Harrys “rightly understood” their team (community) interdependence.

16. RNG: Plato believes as firmly in human nature as any evolutionary psychologist and is trying to find something within human nature that can be cultivated and strengthened so as to make us better than we naturally are. And he locates it in our susceptibility to beauty. He is impressed by how beauty captures our attention, how it enraptures us. (The Greeks in general were unusual in their devotion to beauty.) We love it in the face of a beautiful person like Helen of Troy, or in the thoughts of a beautiful mind like Socrates’s.

17. JB: Far more people can naturally recognize a beautiful face than a beautiful mind. And didn’t his uncomfortable “mental beauty” get Socrates killed? Also, what counts as “human nature” matters—we’ve got the least genetically constrained nature of any species—many aspects of “our nature” are highly culturally configurable (see “Our 1st Nature Needs 2nd Natures”). That empirically includes the degree of self-orientation that’s seen as “natural” within a given culture.

18. RNG: Plato’s quite aware of the fact that our response to the physical beauty of Helen comes more naturally to us than our love for Socrates’s mental beauty (see the Symposium), but he’s eager to try to open more people’s eyes to the other kind of beauty. (Whether everybody’s eyes can be so opened is a question on which he’s highly skeptical, so yes, he is elitist. It’s best to just get that out in the open.) That’s his entire project, in a sense. Philosophy’s project is to open people’s eyes to mental beauty, to moral beauty. If we came to these more abstract kinds of beauty naturally, we wouldn’t require the arduous labors of philosophy. And as far as Socrates’s beauty is concerned, Plato’s writings have ensured that the millennia following 399 BCE, when Socrates was executed by the Athenians (for complicated political reasons far beyond his mental beauty), have recognized what was beautiful in Socrates. Even those non-philosophical masses, of whom Plato tended to despair.

19. JB: Okay, but doesn’t beauty often tempt us away from doing the “right” thing, sometimes into selfishly desiring to own the beautiful? How does Plato think beauty’s better effects can get beyond the happy few who’ve learned to see mental beauty?

20. RNG: The kind of beauty he wants us to love, being abstract, can’t be exclusively possessed, as a beautiful piece of real estate can be possessed, or even as the beautiful Helen can be possessed (the casus belli of the Trojan War). He thought that reality itself could help us out here since it hides a kind of abstract beauty that can only be grasped through the mind, not the senses (a very Greek idea that made the Greeks the progenitors of science as well as philosophy). At first he formulated this beauty in terms of his Theory of Forms, but toward the end of his life, when he was writing the Timaeus and the Laws, it was mathematics that expressed for him the beauty immanent in reality.

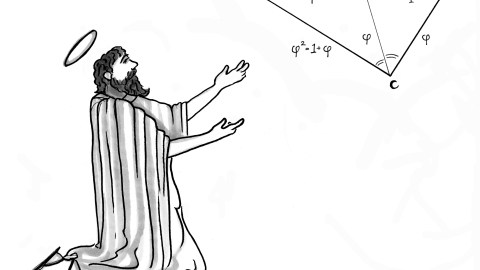

21. JB: That gets us into needing to be clearer about what beauty is, how we recognize it, and why its mathematical forms matter—especially since a seductive form of mathematical beauty is now used to amplify human selfishness (by those once called “worldly philosophers”).

22. RNG: The reason mathematical beauty specifically matters, according to Plato, is that it is immanent in reality itself, or at least in physical processes, and seeing these mathematical relationships in physical reality provides their explanations. (Pythagoras, who had discovered the perfect whole-number ratios that underlie musical chords, was key to this aspect of Plato.) And our seeing all this—the simple mathematical relationships, lovely in themselves, being realized in nature and therefore making what was all tangled and unintelligible before all shiningly transparent now—is itself a profound experience of beauty. And the next step, for Plato, is that the beauty we’re experiencing, which is of a radical, impersonal kind, reorders our souls. It’s not enough for him that he’s laying down an intuition essential to physics, that—as Galileo will put it centuries later—the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. Plato is also proposing, with somewhat heroic optimism (because, despite his sour view of human nature, there’s the abiding hopefulness of the social reformer in him), that the powerful experience of grasping such overwhelming and impersonal beauty can’t help but change us, forcefully bend those vectors of attention outward and make us see our puny selves within some grander perspective.

23. JB: Those hidden mathematical patterns that scientists discover aren’t always simple or “beautiful,” (e.g., Sean Carrol calls aspects of quantum core theory “baroque and unappealing”). And that powerful experience of pattern discovery doesn’t seem to prevent great scientists from sometimes being great jerks (amplifying, not dampening, self-centered, self-aggrandizing arrogance).

24. RNG: Quantum mechanics profoundly disturbs some of our intuitions about reality—which is not so surprising, since we evolved those intuitions to help us navigate our way on the observable macroscopic level, not on the unobservable microscopic level. So, for example, the violence that quantum mechanics, with its hypothesis of non-locality, does to our intuitive notions of causality is apt to make us feel queasily unanchored. But this is quite different from saying that the theory is unappealing mathematically. As Frank Wilczek , a Nobel laureate in physics, says in his book A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design, “Indeed, our modern, astoundingly successful theories of elementary particles, codified in our Core Theory…are rooted in heightened ideas of symmetry that would surely make Plato smile. And when trying to guess what will come next, I often follow Plato’s strategy, proposing objects of mathematical beauty as models for Nature.”

So far as great scientists who are jerks: yes, of course. You can regard Plato’s hopeful view about the moral power of impersonal beauty as a hypothesis he formulated, one that yields the following empirical prediction: Scientists will tend to be more selfless than others; the greater the scientist, the greater the selflessness.

Plato formulated his hypothesis at the first blushing dawn of the sciences, and we’ve now had centuries to provide us with data to test his prediction. I don’t know whether anyone has ever made the effort to do so. I myself would assign it a low probability, based both on my own personal experience of a life spent among scientists and on my own view of moral development. Quite unlike Plato, I would explain moral progress as having far more to do with our attitudes toward other persons than toward impersonal beauty.

But you had asked me why Plato was “besotted” by mathematics, and I’ve tried to explain it. He responded powerfully to its beauty and had a hunch to put that response to work both in understanding physical nature and in morally transforming us. His first hunch has proved wildly successful, his second not so much.

25. JB: It’s intriguing to consider how the degree of selflessness varies in human groups. But loving specific other people seems much likelier to influence more of us than loving abstract mathematical beauty. What would Plato have made of economists who use mathematical rigor and beauty to promote “rational” self-maximization—those “greed is good” folks who literally argue that their mathematics shows that selfishness in markets is morally good because it generates the best collective utility?

26. RNG: Even if such economic models were mathematically beautiful, that wouldn’t count for anything with Plato if the theory itself was morally putrid. He wants mathematical beauty to pull us away from ourselves, not be employed to entrench ourselves ever more deeply in our selfishness.

In some sense, he takes on such rational self-maximalization views in the Gorgias, where he argues with the entertainingly amoral Callicles about the irrationality of narrow self-interest. Callicles might well be an economist of the kind you describe were he living now, and so, too, might the more vulgar Thrasymachus of the Republic (though I see him more in the role of replacing the recently fired Corey Lewandowski as Trump’s campaign manager). Both Callicles and Thrasymachus argue for rational self-maximalization.

And Plato argues against them that the seeming rationality they propound is hideously irrational, since it impedes any moral progress. First of all, rational self-maximalization produces gross inequalities in the well-being distributed among the various citizens, with those not well equipped for rational self-maximization condemned to unsatisfactory lives. Justice forbids letting the well-being of gifted self-maximalizers float the collective average. In the Republic, he writes that the just state is one that does well by all its citizens.

Second, Plato thought that greed corrodes us, that it keeps us slavishly chained to our most narrow point of view, with a low cunning that passes for intelligence. It doesn’t produce that largeness of soul that Plato was after. A greedy, self-centered soul is a pitiful soul, in Plato’s eyes, not experiencing the kind of moral grandeur that realizes our fullest human potential, importing some of the beauty of external reality into the interiority of our own beings.

How wonderful if he had been right that there is a methodology for producing largeness of soul, as he was right that there is a methodology for increasing our knowledge of physical nature, which, since the 19th century, has gone by the name of science. Plato had hopes that the methodology of the latter could become the methodology of the former. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way, but nice try, old man, nice try.

27. JB: Plato’s project of intelligible patterns has been startlingly successful in external science. And I think it’s amazing that Plato got the moral “interiority” diagnosis, if not the cure, correct, the idea that “seeming rationality,” the behavior that’s labeled rational, can produce “hideously irrational” collective results, as it does in the tragedy of the commons or the prisoner’s dilemma game. Can what causes foreseeably bad results rightly be called “rational”?

Thanks, Rebecca—we’ve covered a lot of ground, and you’ve provided much to think about. I look forward to further diablogs, but note in passing that arguably the most successful methodologies for turning our vectors of attention outward, and for “producing largeness of soul,” have largely been “religious.” A topic for another discussion. Thanks again—I feel like I’ve been talking to Plato himself!

28. RNG: Ah, nobody can speak for Plato—perhaps not even Plato, if his Seventh Letter is authentic (in it he claims that he “never committed his true philosophical views to writing“)!

Illustration by Julia Suits, author of The Extraordinary Catalog of Peculiar Inventions, and The New Yorker cartoonist.