To Chip or Not to Chip: Would You Get a Biotech Implant?

In the last ten years, our relationship with technology has practically changed faster than we can keep tabs on it. In 2006, the term “Crackberry” was coined referring to the addictive quality of the Blackberry smartphone, one of the first to achieve widespread popularity in the United States. Now it is already sort of quaint, in a way, to think of us as “addicted” to our phones – for how can we be addicted to something that has become virtually an extension of ourselves?

The incomparable success of such devices has opened the way toward a consumer product revolution. Companies are trying to make everything connect to the rapidly evolving Internet of Things. From fridges to thermostats to home monitoring systems to your car, life is truly becoming hyperconnected. Despite the ubiquity of things that are talking, thinking and sensing everything about and around you, the true spiritual successor to smartphones might be wearable tech. The phone in the pocket evolves into the watch around the wrist, moving our personal technology ever closer to our bodies. Google Glass was a great leap of faith in this direction, a ubiquitous computing platform conceived as a direct extension of our most delicate and treasured of sensory tools, our eyes.

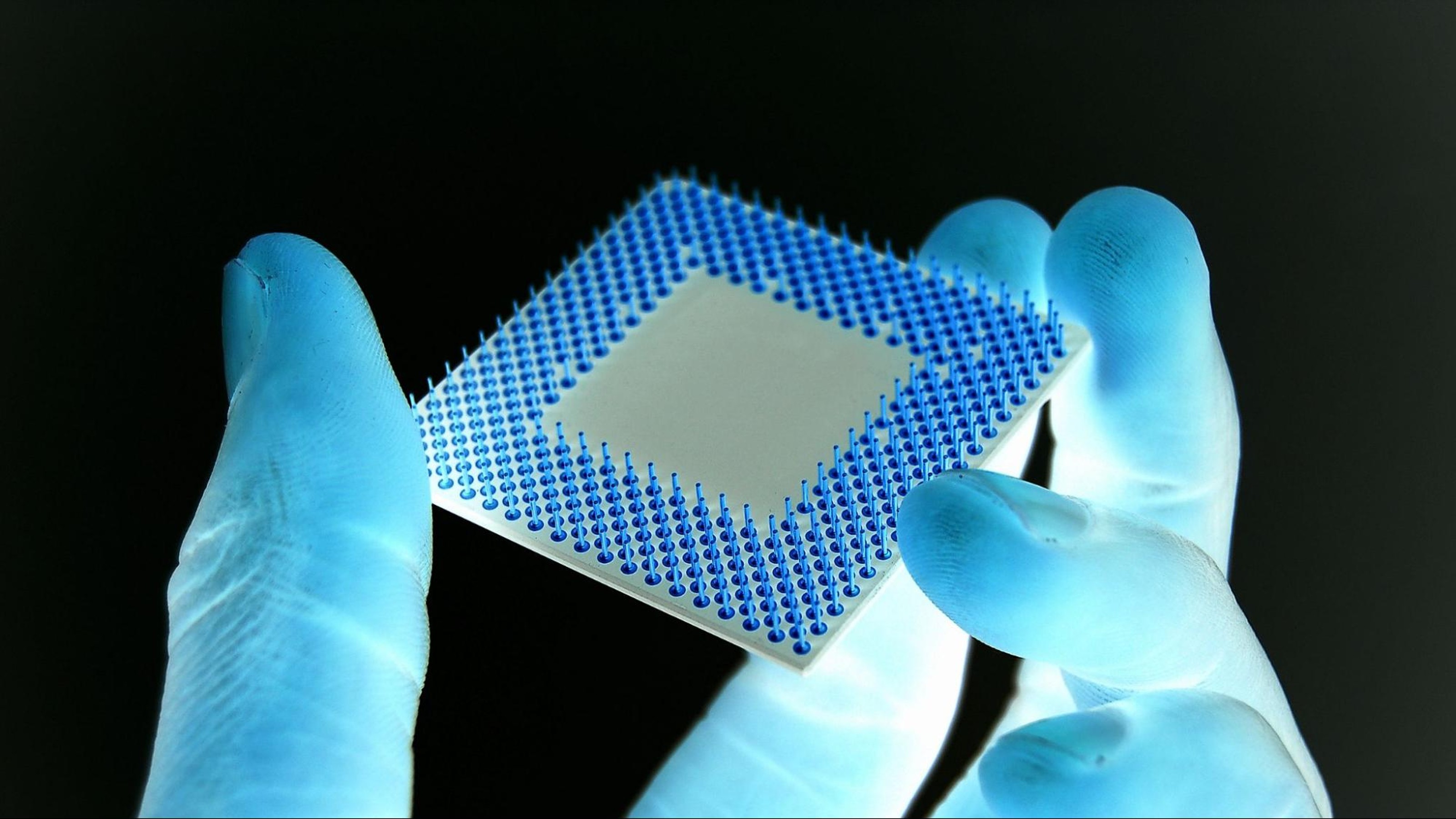

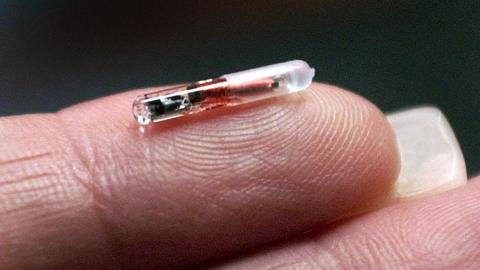

Perhaps you can guess where the tech-enabled rabbit hole goes from here. It seems the next step in our increasingly intimate relationship with technology will be “embeddable tech,” or “being chipped.” Just as we were getting used to the idea of the Internet of Things, the Internet of Everything might already be on the horizon. Having a microchip implanted under one’s skin will dramatically enhance many of the benefits already provided or merely hinted at by smartphones and wearables. A chip under your skin could instantly measure physical metrics such as blood glucose and blood pressure. It could dispense your medication at a precise time and dosage. It would allow you to unlock the front door, check out at the convenience store register, or pay the bus fare with simply the touch of the palm.

Of course, some intrepid folks are already way ahead of the curve. A CNN story from 2014 profiles a small subculture of “self-hackers” who have embedded compasses into their shoulders and magnets in their ears, among other things. One such pioneer, Rich Lee, talks about the “almost erotic” quality of detecting a sensation via embedded technology that was never there before.

But the rest of us might not be so quick to go under the knife and become first-generation (or second-, if you count pacemakers and prosthetics) cyborgs. Smartphones have already gone a long way in showing us some of the perils and tradeoffs inherent in keeping our tech so close to the breast. Google Glass, ambitious a product as it was, has only amplified these issues, causing it to meet with serious pushback on its first wide release. Use of Glass in public areas raised hackles about privacy, tech etiquette, and about users becoming dangerously distracted from having the Internet always right before their eyes. There were also plenty of slightly juvenile observations that alluded to what Google Glass made its wearer look like – a simple but telling reaction suggesting that such a product may simply be ahead of its time.

Putting aside the technology and fashion debate, whether they take on the name implantables or embeddables, these under-the-skin devices will only further magnify such controversies. To be chipped will be to abandon with a sort of finality any pure notion of privacy in one’s life. As intrusive as smartphones can be in recording our daily habits, locations and predilections, at least we have the option to shut them off, leave them home or even throw them into the ocean, if we find ourselves so compelled. Embeddables might end – or at least fundamentally change – our idea of solitude. We will never be alone again.

So would you have a microchip implanted inside you? If you want your voice heard on the question, you can take an MIT AgeLab two-minute survey on embeddable technology. My personal hunch is that for Baby Boomers, Millennials, and those in-between, the question for many might be &%&#! ‘no,’ or a very tentative ‘maybe.’ For the large multigenerational cohort that met the onset of this revolutionary wave of technology as adults, the jump from smartphone to smartchip might simply be too far, too invasive, perhaps even violate of certain convictions about what it means to be human. But those who are born into or are just now growing up in this brave new world will almost certainly feel differently. And for those with deep suspicions, the incredible promise that embeddables contain might become too hard for even modern-day Luddites to resist. If a chip could recover your failing eyesight, would your answer to the above question change? If it could reduce your chances of getting Alzheimer’s? If it could give you superpowers… or even replace the need to find the TV remote? But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Soon all of us will have a choice to make: to simply live within the Internet of Things, or to become part of the Internet of Everything.

MIT AgeLab’s Adam Felts contributed to this article

Photo Credit: Rhona Wise/Getty Images