Paper Tiger: American Moderns on Paper at the Amon Carter Museum

When we think things out, it is usually on paper. Writers scribble random thoughts on scraps near at hand and mine those jotted flashes of insight later for fuller, more realized essays. Artists, however, use paper both for unfinished and finished works—preliminary drawings or paintings pointing forward as well as completely realized art that stands at the end of the process. American Moderns on Paper: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, currently at the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, brings together an amazing collection of American art on that most fragile of supports, paper. These works and artists find themselves together thanks mainly to chronology, which leads to strange and strangely fascinating bedfellows.

In “Galvanizing Hartford,” Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser’s introductory essay in the catalogue to the exhibition, she discusses the long and varied history of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art’s approach to collecting works on paper. Of the 1,500 works on paper in their collection, the lion’s share originate in the twentieth century, when museums began to recognize the value of watercolors and drawings and seek them out for their collections. Part of that realization of the value of modern American art came from how American artists began to digest the meanings of the modern art of their European counterparts. Much American art of the twentieth century is a struggle with the lessons of European modernism. That struggle plays out vividly on paper, where the American art tigers sharpened their claws and took a good swipe at Europe in a quest for global art dominance.

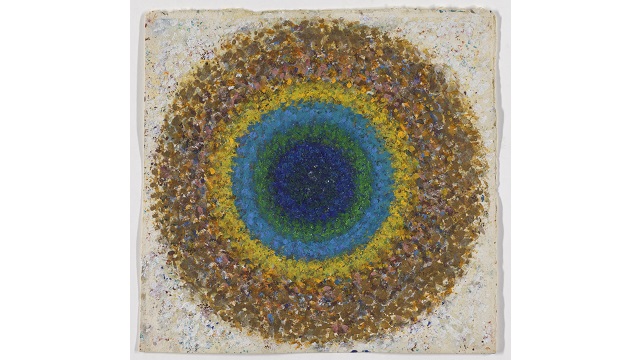

And, yet, not all of that struggle roars with defiance. Quieter works such as Andrew Wyeth’s 1956 watercolor Granddaughter (shown here) also speak volumes in regards to what American artists had to say on paper. Wyeth’s work finds itself in a chronological conundrum, trapped amongst the Abstract Expressionists of that era. Wyeth’s defiance on paper comes from a stubborn grip on the past and a dismissal of the flash and dash of the here and now and of the personal and individual. Lumped together with pieces by William Baziotes, Mark Tobey, Ellsworth Kelly, and others, Wyeth’s work is the exception that proves the rule of American modernism, in which people could chose to go anywhere, including the past.

American Moderns on Paper gathers together all the usual suspects, from Georgia O’Keeffe to Edward Hopper to the Eight to John Marin, yet it is in the little known artists that the true wonders emerge. The weirdly wonderful surrealism of Eugene Berman and the neo-romanticism of Pavel Tchelitchew will stick to your senses like sweet taffy. Sadly, the fragility of works on paper often dooms such artists to the obscurity of museum storage areas. In this exhibition, at least, they see the light of day and may gain a place in the sun for themselves.

So many of these American artists demonstrated a tiger of a mind pouncing and devouring the ideas of European modernism. American Moderns on Paper documents that positive paper tiger mentality and pays tribute not only to the vision of the artists, but also to the vision of a museum that pursued the writing on the wall of a key moment in American cultural development.

[Image: Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009). Granddaughter, 1956. Dry brush and opaque watercolor on thick wove paper. © Andrew Wyeth. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; Gift of Mrs. Robert Montgomery, 1991.79. wadsworth9.]

[Many thanks to the Amon Carter Museum for providing me with the image above and catalogue from American Moderns on Paper: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, which runs through May 30, 2010.]