Mathematics explains why non-conformists always end up looking alike

- Anti-conformists have an odd way of ending up looking like each other.

- A Brandeis mathematician looks at how this synchronicity occurs.

- Understanding the mechanism behind non-conformist conformity has applications in other areas, like the stock market.

We’re here for such a short time, and we’d like to think we matter. “I’m not just one more person — I’m different.” That’s true, and also… not. We’re very much like one another, though the particular details of our lives are, of course, pretty unique. Still, particularly in the Western world, we like to be seen as separate from — and better than? — the herd. Many of us go out of our way to look different than “them,” too, declaring our uniqueness in our appearance.

So, how come so many individual anti-conformists end up looking alike? It’s called the “hipster effect,” and a study from Brandeis University mathematician Jonathan Touboul explains how it happens.

It’s not just an issue of visual fashion, by the way. As Touboul tells Technology Review, “Beyond the choice of the best suit to wear this winter, this study may have important implications in understanding synchronization of nerve cells, investment strategies in finance, or emergent dynamics in social science.”

Image source: LDWYTN / Shutterstock

The purpose of the study

While anti-conformists may, at first, succeed in devising their own personal brand of sartorial rebelliousness, it’s followed by an inevitable, if unintentional, synchronization around a single appearance. Touboul’s study looks at how such people seem to inevitably become synchronized. He suspects that a major influence on the way it happens may be the speed of propagation of styles through a culture.

Not everyone learns about or adopts new styles in the same way. Some follow fashion closely, some go by word of mouth, and some emulate the appearance of well-known individuals they admire. In the latter case, the tipping-point may occur after a mutually-revered celebrity adopts a new fashion.

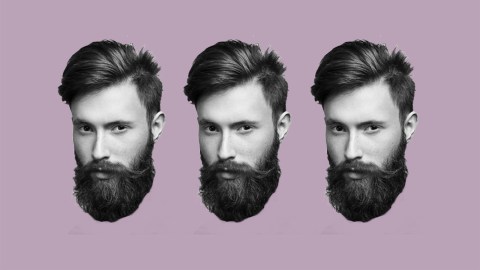

(Toubal)

Modeling individuality

In Touboul’s simple model, one is either a member of the mainstream or a hipster (no snarky connotation intended), and he explores different hipster-to-mainstream ratios. He also factors in different amounts of time it might take a hipster to detect a new style and respond to it.

Simple as his model is, Touboul has found that experimenting with those two factors produces a surprisingly complex set of behaviors, though synchronization always occurs. Even when he revises his model to allow for more than two types of people, synchronization still occurs.

Often, of course, roles may swap when there are so many hipsters that they become the mainstream. “For example,” says Touboul, “if a majority of individuals shave their beard, then most hipsters will want to grow a beard, and if this trend propagates to a majority of the population, it will lead to new, synchronized, switch to shaving.” An odd sudden swap occurs when the number of mainstreamers and hipsters is roughly equal — everybody winds up switching together between different trends.

Next up

Answering why this last phenomenon occurs is an area cited by Touboul for further study.

It also bears saying that Touboul’s modeling isn’t really just about hipsters — it’s about the manner in which any group of people suddenly decide to act in lockstep contrary to the mainstream. One example he mentions would be the stock market, in which a number of investors may suddenly conclude there’s money to be made in acting contrary to the majority attitude.

A deeper understanding of the dynamics underlying such events, which new research hopefully will provide, would obviously be helpful.