Art Boom

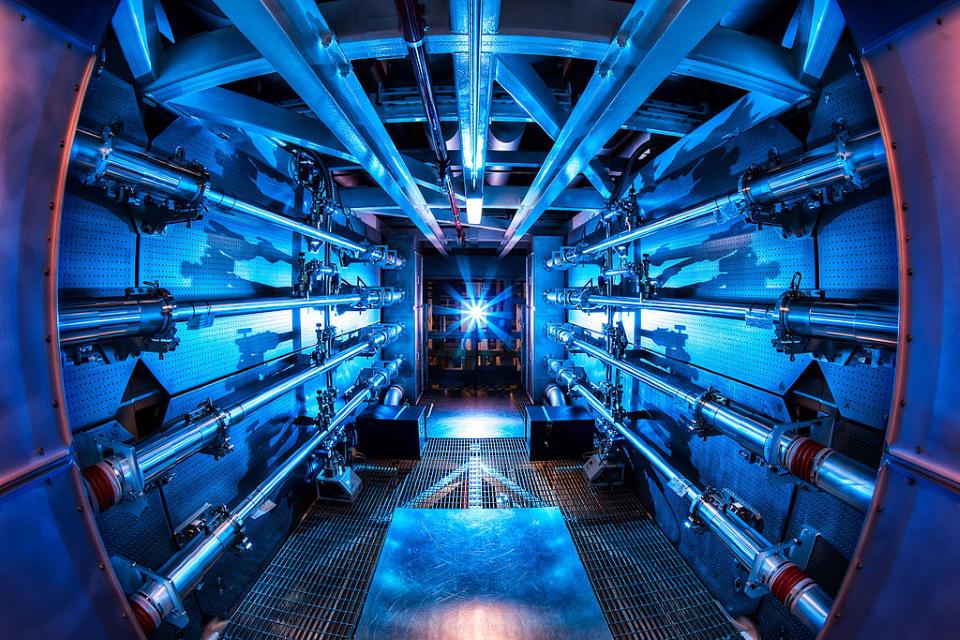

The word “explosive” is use to describe a lot of artists’ work. In the case of Cai Guo-Qiang, he actually earns the adjective. Last month, the Chinese artist inaugurated his Fallen Blossoms exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art with a blast on the same steps that Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky character raced up. Literally drawing with gunpowder, and then igniting it, Cai challenges the staid art world to wake up and smell the pyrotechnics. His art sends shockwaves through the viewer and ignites the fuse to further musings.

Cai began working with gunpowder in his art in the mid 1980s as a way of resisting the repressive Chinese government. The artist wanted his work not to just quietly condemn the hard liners but to say it loud and proud. Instead of staring down a tank, Cai wanted to blow it up, beautifully. The fact that the Chinese invented gunpowder somewhere in the ninth century made it an apt emblem for both Chinese culture and the violence often used to repress that culture in the name of order. More recently, however, Cai has worked from the inside to hollow out the power of the repressive Chinese regime. The fireworks show he organized for the opening of the 2008 Beijing Olympics helped the Chinese government show a better face to the world.

Fallen Blossoms concentrates on the impermanence of life rather than the seeming permanence of tyranny. If you watch the YouTube video of the PMA explosion, you can see that the petering out of the blast was as important, if not more so, than the big bang. Later in the same evening, Cai appeared at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia to detonate a 120-foot-long drawing of gunpowder on silk titled Time Scroll. The scorched Time Scroll was then placed in an artificial “river” in which running water would slowly wash the work away during the exhibition.

Although Cai’s main intent seems to be to make us conscious of our mortality, a secondary, and perhaps more lingering effect seems to be a revelation of just how much we love the idea of danger, even to the point of finding it beautiful. Such fascination goes beyond the oohs and ahhs of fireworks crowds and implosion junkies to a real celebration of the power to destroy. Watch and listen to the crowd in the YouTube video of the explosion and you won’t come away thinking of your mortality. It’s interesting how Cai’s exhibition coincides with the Met’s Art of the Samurai show, which concentrates on how the samurai identified intimately with their weaponry. In the same sense, even in this age of car bomb carnage on the nightly news, we, too, identify intimately with our weaponry, whether it be old fashioned explosives or high-tech Predator drones. This appetite for destruction craves kabooms like carbohydrates. Whether we like it or not, Americans live by the sword and die by the sword, even if we wield that sword second-hand through our tax dollars. The flaming flower pattern of Cai’s Fallen Blossoms explosive display contains the same fearful symmetry of the atomic bombing mushroom clouds that blossomed over Japanese cities to close out World War II. Such art is both terrible and sublime in equal parts, reflecting the human capacity to both create and destroy our world and ourselves.

I’ve ventured far from Cai’s intentions, but I think he’d be among the first to accept the idea that his explosions can ripple out in ways beyond his control. Each creative act is a detonation that lights the fuse for additional sparks of insight in those who look and think. Fallen Blossoms is a perfect way to launch this blog and push the boundaries of what art is and has been and can mean to us today. Please join me in this adventure of eye, mind, and heart. It’ll be a blast!