All in the Family

“My pictures are like a family, each one has a special niche in my heart,” renowned art collector Chester Dale once said. “Does anyone ever place a dollars-and-cents value on a son or daughter? If they do, they don’t deserve them.” With his first wife Maud, Dale amassed perhaps the greatest collection of French art from the Impressionists to the Modernists. Upon his death in 1962, the childless Dale left his most lasting legacy—his collection—to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, with two conditions: one, that they be displayed together in a gallery bearing his name; and two, that the works never be loaned out. He wanted his family kept together forever. The NGA’s new exhibition From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collectionis truly a family affair.

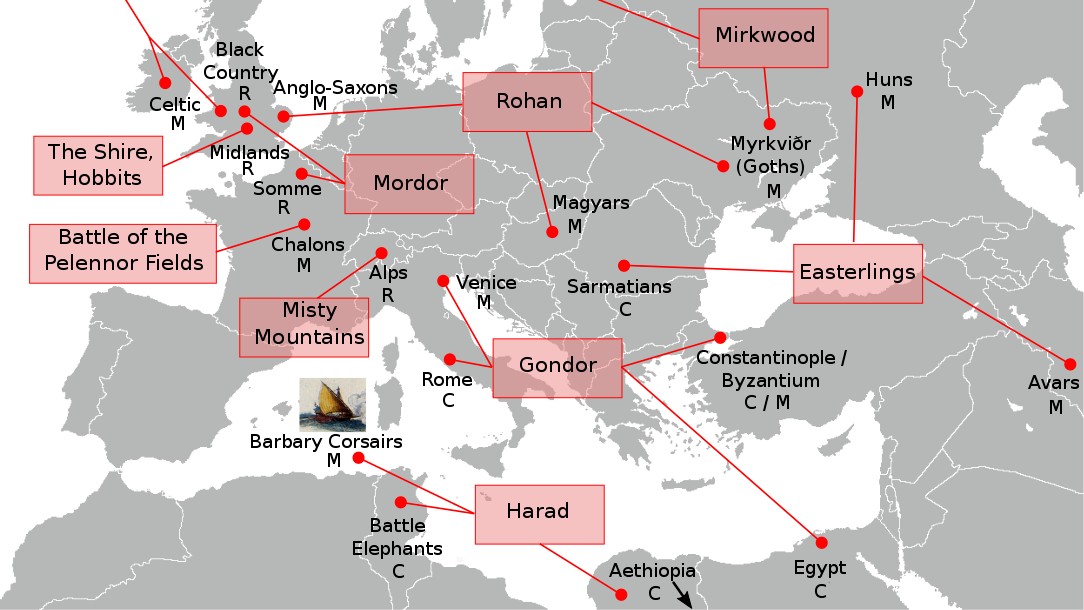

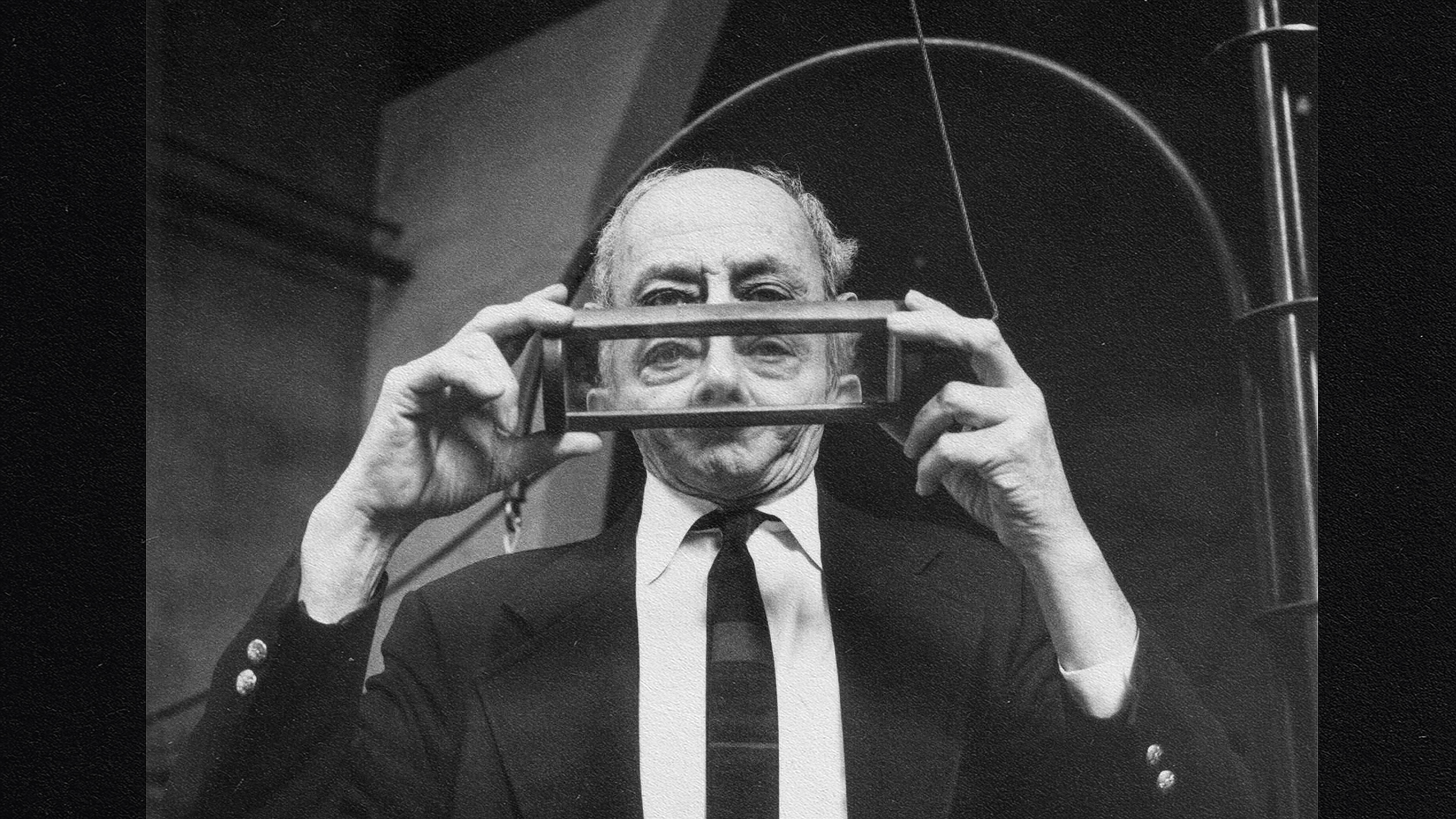

Dale, known affectionately as “Chesterdale” by his wives and close friends, made his fortune in the stock market, starting at the bottom as a Wall Street runner and working his way to the top. Briefly a professional boxer, Dale never lost his taste for a good scrap. In the competitive worlds of business and art collecting, Chesterdale reigned as the champ. Dale not only collected art, but also collected artists—as friends. George Bellows, Diego Rivera, Salvador Dalí, and others became close friends and sealed that friendship with deeply personal portraits, such as Dalí’s surrealistic portrait of Dale with his dog (pictured).

In a just world, the collection would be named after both Chester and Maud Dale. “Maud was the advisor, the face, and the voice of the Dale collection,” Maygene Daniels writes in the catalogue, “while Chester had the gamesmanship, boundless self-confidence, and acquisitiveness that brought it into being.” This “dynamic and unusual partnership” is given full due in the catalogue to the exhibition, if not in the title. Maud not only help select the collection but also curated exhibitions in the early 1930s at the Museum of French Art, which served at the time as the de facto Dale museum. When Maud died in 1953, Chester, who suffered a heart attack a year later, slowed down his collecting greatly. Without Maud, the heart of the collection, the “family” never felt whole again.

The range of the Dale collection is stunning. Degas’ Four Dancers, Renoir’s A Girl with a Watering Can, Cassatt’s The Boating Party, Picasso’s Family of Saltimbanques, and Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, West Façade are just some of the iconic paintings gracing the collection—the cherished children Chester and Maud Dale have left behind. We are richer as a nation for their generosity. “The Dale bequest did not merely enrich the National Gallery of Art,” Kimberly A. Jones concludes in her essay, “it permanently transformed the museum in a way few collectors can ever hope to achieve.” From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collection transforms “Chesterdale” from just a name on a wall to a living presence in the gallery today.

[Image:Salvador Dalí,Chester Dale, 1958,oil on canvas. Overall: 88.8 x 58.9 cm (34 15/16 x 23 3/16 in.); framed: 111.7 x 81.3 x 6 cm (44 x 32 x 2 3/8 in.). Chester Dale Collection.]

[Many thanks to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, for providing me with the image from and catalog to From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collection, which runs from January 31, through July 31, 2011.]