What American Art Can Teach Us About American History

English speakers commonly translate the French nature morte as “still life,” but a more accurate translation would be the oxymoronic “dead life.” Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life, a new exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, brings the American still life tradition back from the dead to say something about the American past, present, and future. From the very beginnings of American art in the early 19th century, still life’s taken the stuff of Americans to illustrate the stuff of American dreams and memory. These “object lessons” allow the “talking dead” of inanimate objects to animate debate about what we once were and hoped to become as well as what we are today as a nation and people.

As Bill Brown points out in the catalog to the exhibition, the European tradition of still life, specifically the Dutch tradition, “convey[s] a milieu of spectacular excess,” whereas “the particular and particularizing work of American still life extracts objects from the object cultures in which they participate.” American still life invites introspection and deep reading beyond sensual, surface delight by holding up our possessions to examine the hold they possess on us. “Just as trivial objects had focused the dispute that led to the politically independent state,” Brown continues, “so too they focused assessments of the cultural independence of the nation.” The taxing of things ignited the American Revolution, in other words, but all the smaller American revolutions grew out of our consumer culture as well, from owning slaves to owning guns to owning computers.

Still life’s traditionally found itself on the bottom of the genre totem pole. “From the beginning, American still-life painters labored under a burden of disrespect,” Carol Troyen explains in the catalog. How could flowers or a plate of delicacies compete with grand history paintings of big events? Audubon to Warhol argues that still life painting IS history painting, but the history of the ordinary rather than the extraordinary, the masses rather than the elite. “If we really want to know what is going on in this country, the artists, curators, critics, and scholars of still life have told us,” Katie A. Pfohl argues in her essay. “We had best set our sights low, since it is often — both then and now — through its stuff that America really speaks.” By setting its sights low, Audubon to Warhol sets its sights high on targeting essential truths about the American experience.

Philadelphia’s the perfect venue for celebrating American still life as not only “The Birthplace of America,” but also the birthplace of the genre as practiced by Americans, first and foremost by the Peale family, led by patriarch Charles Willson Peale. Peale passed down his dual loves for art and natural history to his sons and daughters, especially the artistically named Raphaelle, Rubens, and Titian. In Rubens Peale with a Geranium (shown above), Rembrandt Peale captures his near-sighted, naturalist brother with a botanical specimen. Such works capture the precision and exactitude of the Peale family approach to still life as well as the human component. At that moment in early American history when the young country began discovering not just the untamed wilderness to the West, but also the untamed elements of within democracy, such still life spoke of more than just young men and flowers.

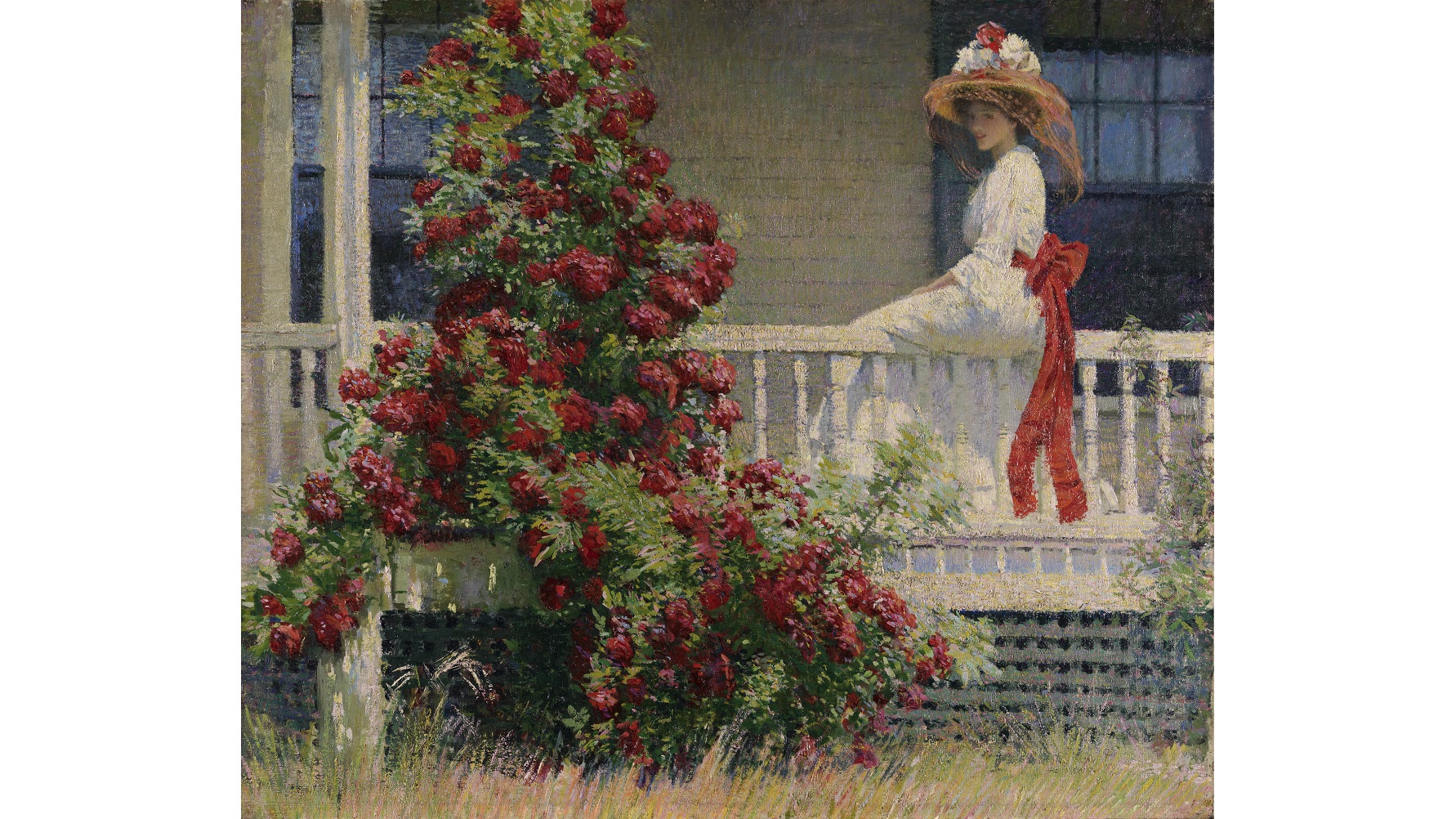

As “Manifest Destiny” bloomed across the continent, artists captured this flowering of American life. Severin Roesen‘s Flower Still Life with Bird’s Nest (shown above, from 1853) captures this exuberant feeling as Americans began to consume the landscape as part of the larger continental conquest. Yet, at the same time that it shows off, Roesen’s still life looks in. Each flower partakes of the “language of flowers” well known through the 19th century, but forgotten today. Together, the bouquet speaks symbolically in a complex, multifaceted way. Touchscreens in the gallery near this painting invite you to “say it with flowers” to compose a floral self-portrait based in which your personality is symbolized by certain floral connections. The paintings in this section deceive you with flash and color hiding a lingering undertone of introspection that runs throughout American still life’s history.

The Civil War changed America forever, with still life reflecting that change. Antebellum excess gave way to austerity and trompe l’oeil illusionism, as exemplified by William Michael Harnett‘s After the Hunt (shown above, from 1885). As much as it blurred the line between the real and illusory, After the Hunt likewise blurred the line between fine art and mainstream culture. Exhibited in a New York City saloon, After the Hunt served as a “game changer,” curator Mark D. Mitchell explained at the press preview, by making still life a spectator sport of sorts and making questions of seeing and believing public concerns. Mitchell recreates the saloon parlor experience with seating that invites modern viewers to ask the same questions today that late 19th century Americans asked as they tried to piece back together the fractured union.

The illusionism of Harnett and the other great American illusionist, John Frederick Peto, tempts you to touch the paintings to confirm what is and isn’t real. American still life continually tries to come into contact with the present and how the past lingers on through objects flavored by memory. Reminiscences of 1865 (shown above) evokes memories of “Honest Abe” Lincoln, but from the year 1904 “in an informal shrine that includes his engraved portrait and his life dates carved in positive and negative on a green-painted door,” Mitchell observes. Looking back from the corruption of 1904, Peto may be nostalgic for the political good old days, yet still conscious at least in part of the dirty politics that led to Lincoln’s death. Such an arrangement of suggestive totems literally opens a door onto the past that speaks volumes about the present.

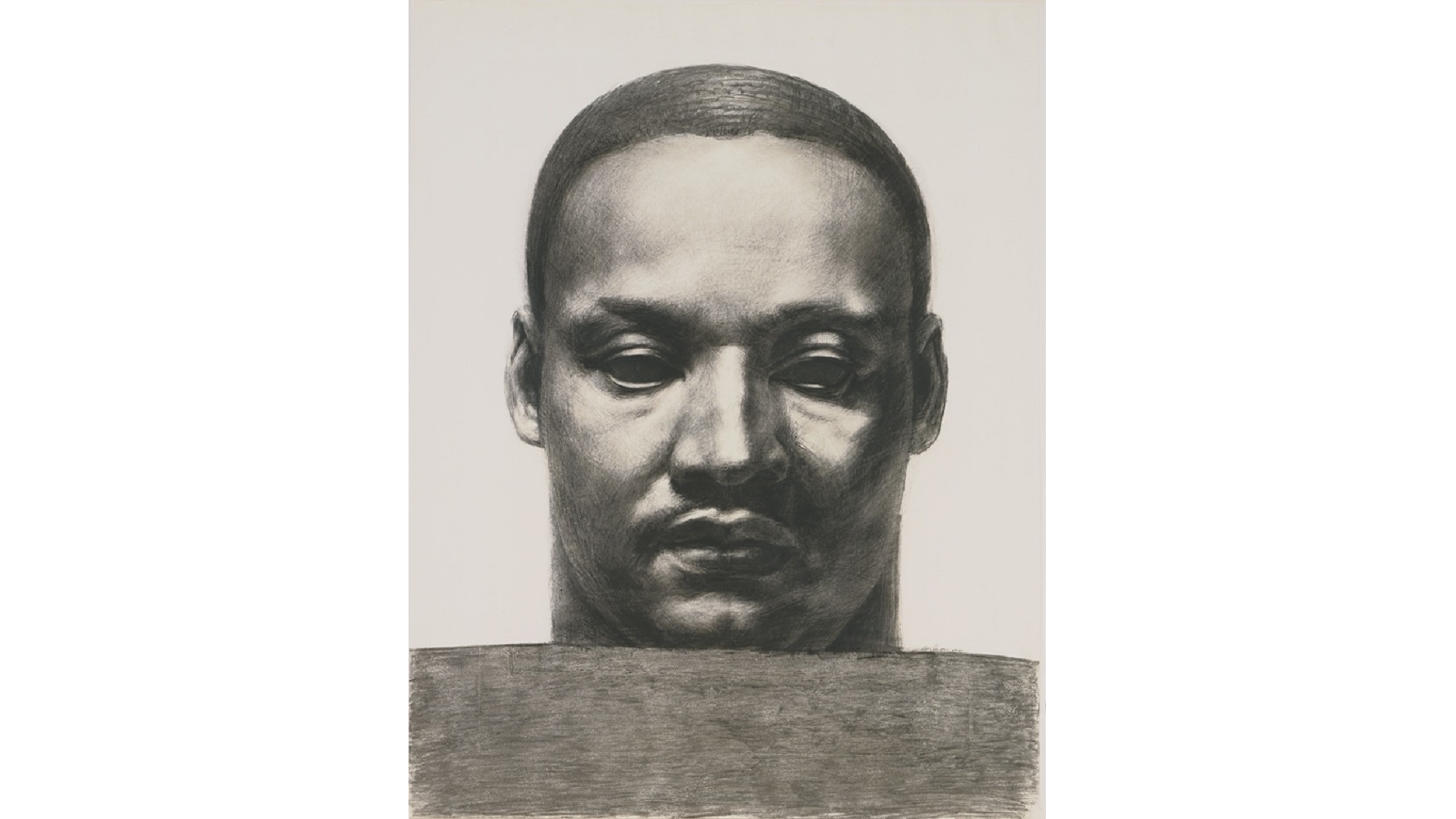

Walking through this exhibition of the “talking dead,” I couldn’t help but be conscious of the languages we’ve lost. We can no longer “read” the flowers in Roesen’s still life. We can no longer even read the meticulously reproduced musical notes in Harnett’s The Old Violin. The exhibition does a wonderful job of reclaiming lost voices of women (including the Peale daughters Sarah and Margaretta) and African-Americans (most notably Robert Seldon Duncanson) to fill out the larger American narrative in still life, but even it cannot help us recover and rediscover these lost languages that make up the larger language of how we relate to things as Americans. Twenty-first century Americans no longer have “hands on” knowledge of nature and culture, to our tragic loss.

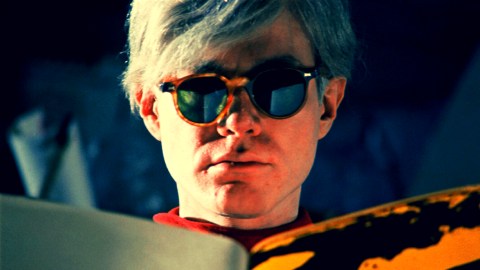

Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life, as promised in the title, concludes with Andy Warhol and Pop Art, the modern art movement dedicated to raising questions about the consumer culture we’ve built by fetishizing even Brillo Boxes (shown above) and their garish advertising scheme. The introspection begun with Peale ends in the introspection of Pop. Yet even this endpoint in Warhol feels not so much as an ending as a new departure. What is the still life of today? More importantly, what does it say about us as Americans now? Paint gives way to pixels. Lost languages give way to virtual reality. What is the typical Facebook page — built from the fragments of everyday life in photos, links, and “likes” — but our own personal still life? Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life succeeds in waking us to the “talking dead” of the past, far and near, but may also succeed in waking us to how we’ve lost touch with the world around us and, consequently, what being an American is supposed to be.

—

Bob Duggan has Master’s Degrees in English Literature and Education and is not afraid to use them. Born and raised in Philadelphia, PA, he has always been fascinated by art and brings an informed amateur’s eye to the conversation.

[Image at top of post:Reminiscences of 1865 (detail), 1904. John Frederick Peto, American, 1854-1907. Oil on canvas, 30 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 cm). Framed: 41 7/8 × 31 7/8 × 2 1/4 inches (106.4 × 81 × 5.7 cm). Lent by The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Julia B. Bigelow Fund by John Bigelow.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with the images above from, other press materials related to, a review copy of the catalog for, and an invitation to the press preview for the exhibition Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life, which runs through January 10, 2016.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]