Gothic Tale: A Biography of Grant Wood

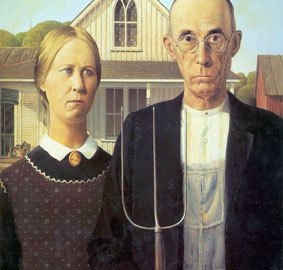

“I’m the plainest kind of fellow you can find,” painter Grant Wood told an interviewer in the 1930s, the height of his fame. “There isn’t a single thing I’ve done, or experienced, that’s been even the least bit exciting.” In Grant Wood: A Life, R. Tripp Evans demonstrates just how deceitful Wood’s protestations really were. Instead of the well-worn tale of normalcy beyond compare, Evans, an art history professor from Wheaton College in Massachusetts, weaves a more gothic tale of subversion and submersion that reveals a new view of Wood as a tortured homosexual artist miscast as a purveyor of Reagan-esque Americana in works such as the iconic American Gothic (shown above). Through new readings of the works themselves as well as of Wood’s posthumous existence in the popular consciousness, Evans gives us the Grant Wood that the artist himself never could.

Born into a highly conservative and homophobic time and place, the Midwestern Wood of the early twentieth century longed to be an artist while still finding acceptance in the home of his childhood. Wood carefully crafted a persona of a “farmer-painter” despite never actually farming himself. That persona “as the Artist in Overalls,” Evans explains, “allowed Wood to simply vanish when he appeared in his street clothes.” Unfortunately, that vanishing act extended to all aspects of the artist’s true self and forced him to embed his hidden self into his paintings—a secret life hidden in plain view. Despite these outward clues, critics willfully misread Wood’s art and person from the very beginning. “Rather than presenting Wood and his work as paradigms of Depression-era America, as so many have done,” Evans proposes, “this study seeks to illuminate the profound and fertile disconnection between the artist and his period.” Just as the woman in American Gothic averts her gaze from the viewer, critics have averted their eyes from the obvious unsettledness of such images and chosen to see instead a full-throated salute to a golden age of the past based on a mythical Midwest as a repository of all things American and, therefore, all things godly and good. Giving Grant Wood his life back, as Evans does, not only clears the record of the past, but also clears the record of the American present, which continues to cling to this Midwestern mythology in politics and culture as a stay against progress and tolerance, including tolerance of homosexuality.

One of the most striking images in the book is that of a young Grant Wood sitting at a Parisian café in 1920, cigarette in hand and bohemian beard on his chin. Studying art and simply living in Paris at that time meant living la vie boheme, which meant embracing modernism in art and a very un-American degree of sexual freedom. Upon his return to Iowa, friends and family besieged Wood to shave off the beard, which he did after enduring a week of complaints. It was as if Wood could remove his Parisian experience (and his sexual orientation) as simply as a set of whiskers. When searching for a title for his autobiography, Wood chose Return from Bohemia, a telling choice for a man whom many could never picture going there in the first place. In many ways, Evans’ book is a Return to Bohemia in regards to restoring Wood’s European roots (including exposure to the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity movement in Germany) and the sexual identity he may have explored on those travels (especially during the homophilic era of the Weimar Republic).

Evans excels in dismissing the “superficial folksiness” of overly familiar works such as American Gothic, which he sees as Wood’s attempt “to confront the complicated feelings he held for the places and people of his childhood.” Although Wood’s sister Nan and his dentist posed for the two figures in the painting, Evans sees the work as “a kind of double exposure” in which the two stand in for the artist’s parents and all the accompanying emotional baggage such a connection would bring. Instead of a bravura display of manly American bravado, American Gothic engages us with “an extraordinary sense of restraint, strength, and inventive subversion—all of which more accurately reflect the work’s ‘gay sensibility.’” For Evans, the “gothic” in American Gothic and all of Wood’s oeuvre descends from gothic literary genre with its “similarly complex matrix of unorthodox family relationships, sexual anxiety, and a recurring fascination with death.” When Wood’s dentist posed for the father figure in American Gothic, Wood replaced his square-framed glasses with the same round-framed style his father once wore. In the same way, Evans replaces the lenses we’ve viewed Woods through all these years and brings him into focus for both Wood’s time and ours.

After the immediate success of American Gothic, Wood found himself anointed as a Regionalist by the homophobic Thomas Hart Benton. The diminutive Benton presented Regionalism as a manly kind of art as a way of measuring up to a standard of masculinity opposed to homosexuality. Suddenly, Wood found himself not only hiding his orientation but actually involved in a movement condemning it. The pressures of this tangled web of associations essentially closed off all creativity for Wood, who produced barely a handful of works between 1936 and his death in 1942. One work, a 1937 lithograph titled Sultry Night, featured a full-frontal male nude cooling himself off with a bucket of water. The U.S. Postal system refused to deliver copies of Sultry Night, labeling it (but not similar female nudes) as pornography. That work and other male nudes in this final period show the cracks forming in the façade Wood had built up over the years.

After his death, critics quickly covered over these cracks, connecting Sultry Nude to classical allusions free of any taint of homosexuality. Wood’s sister Nan fiercely defended her brother’s manhood posthumously and stood in the way of any biographer who would say otherwise. Retrospectives since Wood’s death continually emphasized the simple “Artist in Overalls” Wood to the exclusion of any other. Against that long tidal wave of deception, R. Tripp Evans‘ Grant Wood: A Life swims bravely against the current. I read Evans’ book not long after the unfortunate suicide of Rutgers’ student Tyler Clementi after a homophobic hazing incident. Grant Wood: A Life is about much more than a single artist’s life. It’s about the life (and too often death) of so many people today fighting against intolerance in their individual lives. If Evans’ book can open the eyes of people to the self-destructiveness of the myth Grant Wood came to personify, then this is a gothic tale with a happy ending.