Back to the Garden: The Pastoral Vision in Britain at the Delaware Art Museum

“And we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden,” Crosby, Stills, and Nash sang in “Woodstock,” the song that tried to capture the spirit of the generation-defining gathering. For artists working in Britain after the Romantic movement, getting back to the garden—getting back to a sense of the natural world as a spiritual realm—became the top priority. The Pastoral Vision: British Prints 1800—Present currently at the Delaware Art Museum traces the way artists tried to picture the pastoral aspect of British Romanticism over the course of two centuries. The results reveal much about both the art of printmaking and the art of depicting the abstract lurking in tangible reality.

Before the advent of photographic reproduction, printmaking served as the main resource for artists to distribute their images to the general public. Even an artist as renowned as J.M.W. Turner tapped into the power of the print to generate a wider representation at home and abroad, especially, at least for Turner, in America. Printmaking thus became the media by which artists could communicate to the largest possible audience in a visual way. The pastoral vision of nature as “heaven on earth” flows from much of the poetry of the British Romantics, especially that of Wordsworth, but it is the art of William Blake that set the stage for the pastoral idylls envisioned in the works of this exhibition.

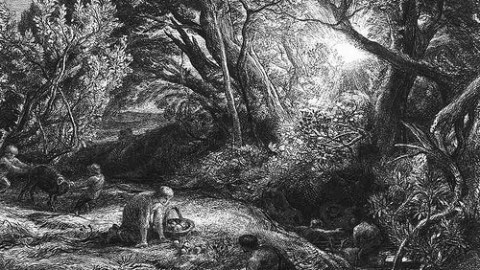

Calling themselves “the Ancients,” Samuel Palmer, George Richmond, Edward Calvert, and others followed the example of Blake in seeking some ancient, mystical truth behind the façade of nature’s surface reality. Palmer’s 1861 print Morning of Life (shown) exemplifies this pasting of fervent piety onto pastoral scenes. The florid rendering of the flora attempts to convey the richness and overflowing spiritual power of the scene, which Palmer etched on the spot thanks to the immediacy that the etching technique offered to an artist with the talent capable of harnessing it.

After that glorious moment in the garden, however, came the inevitable fall in the form of the Industrial Revolution—the “dark, Satanic mills” Blake saw looming on the horizon. The Pastoral Vision follows the post-lapsarian depictions in British prints of James McNeill Whistler, Seymour Haden, and others. As Romanticism gave way to Victorianism and Modernism, the importance of the print and a spiritual connection to nature wavered in parallel. The exhibition also shows the brief revival of the etching technique in the early twentieth century, as some artists sought to recapture the bright spark of divinity of Blake and “the Ancients” by emulating their printmaking style.

Prints by contemporary artist Rachel Whiteread, a member of the angry Young British Artists movement headed by the notorious Damien Hirst, cap off the progression, or perhaps better put, the devolution, of the print-based pastoral vision in Britain. Whiteread’s Demolition series of screen prints presents scenes of destruction and division that make you wonder whether the idea of the pastoral (or any other culturally generated idea, for that matter) has come apart in the modern era or, perhaps more troublingly, never really cohered in any significant way in the first place. The mystical ramblings of Blake and his followers take on a whole new meaning through the questioning of Whitehead’s contribution, forcing you to go back to the garden, back to the beginning of the exhibition and the pastoral print tradition, and reevaluate everything they (and you) may have thought you knew for sure. In this way, at least the exhibition itself, if not the idea it studies, hangs together in a coherent, thought-provoking manner.

As always, works on paper fascinate if for no other reason for the fleeing moment that they are allowed to be seen by the public due to their fragile nature. Fragile nature, and the even more fragile conception of spirituality behind that nature, live on in the prints of The Pastoral Vision for us to view and ask where we fit in today in the age of Global Warming, the bastard child of the Industrial Revolution. Look upon these works and think back, but think of the future, our future, as well.

[Image:Morning of Life, 1861. Samuel Palmer (1805-1881). Etching, 5 3/8 x 8 1/8 inches. Gift of Dr. Charles Lee Reese, 1940.]

[Many thanks to the Delaware Art Museum for providing me with the image above and press materials for The Pastoral Vision: British Prints 1800—Present, which runs through August 15, 2010.]