How the Nazis Tried to Turn a Slow Defeat into a Propaganda Victory

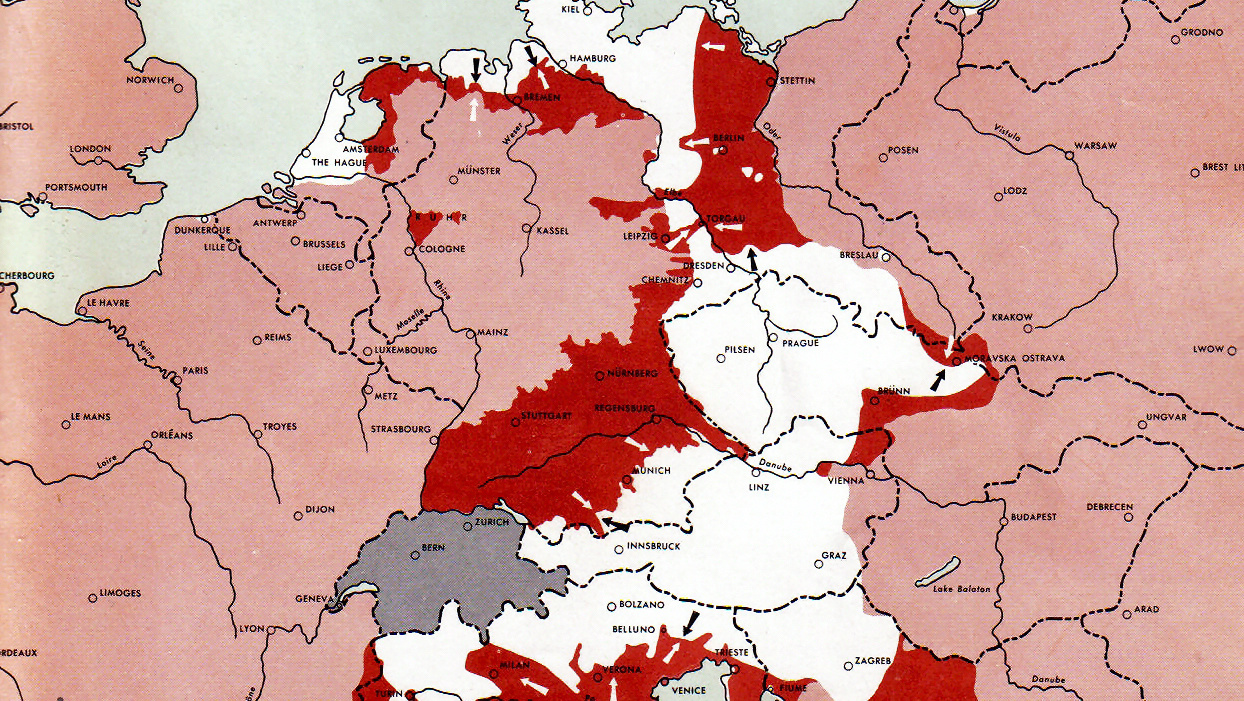

The end of Nazi Germany in two words? Pincer movement [1].

After it turns the tide at the bloody battles of Stalingrad (August 1942 – January 1943) and Kursk (July – August 1943), the Red Army relentlessly steamrollers westward to Berlin. The Anglo-American push eastward, also in the general direction of the Führerbunker[2], occurs quite a bit later. D-Day is June 6th, 1944. From their bridgehead in Normandy, the western allies rush through France, the Low Countries and Germany proper in an attempt to match the Red Army’s unstoppable advance.

That’s the thumbnail version of history. A close-up reveals a more complex picture. The landing in Normandy was preceded by another Allied incursion into Axis-controlled [3] Europe: the invasion of Italy, on 3 September 1943 [4]. But even though the Italian Campaign turned out to be the costliest of all operations by the western Allies in Europe in terms of infantry casualties [5], it ultimately was inconsequential for the outcome of the war. German troops in northern Italy surrendered less than a week before V-E Day [6] on 8 May 1945.

Faced with the Allied invasion, the fascist state in Italy quickly crumbled. Mussolini was arrested on 26 July, and an armistice with the Allies concluded by early September 1943. The Wehrmacht took over the defence of the Italian peninsula, slowing down the Allied advance by strategically withdrawing behind successive defensive lines:

(1) The Volturno Line (a.k.a. the Victor Line) is the first, southernmost line. It ran from the Tyrrhenian coast on the west of the peninsula, at Castel Volturno, 20 miles north of Naples, up the Volturno river inland, and then down the Biferno river to where it debouches into the Adriatic, on the eastern coast of Italy, in the city of Termoli. The Germans abandoned the Volturno Line on 12 October 1943, falling back onto the Barbara Line.

(2) The Barbara Line, situated about 20 miles north of the Volturno Line, following a series of hilltop fortifications and, towards the Adriatic, the Trigno river. The line was breached in early November 1943.

(3) Next, and more prominently, was the Gustav Line (a.k.a. the Winter Line), from just north of the Garigliano river in the west to the Sangro river in the east. At its centre, in the Apennine Mountains, stood the abbey of Monte Cassino, a major obstacle on the Allied march to Rome. It took the Allies several protracted battles, great loss of life and half a year to break through. The Garigliano is reported to have run red with the blood of the thousands of fallen. A fallback line associated with the Gustav Line was called the Adolf Hitler Line, until it became clear in early May 1944 that it would soon be breached; at the insistence of Hitler himself, it was then renamed the Senger Line – after a German general [7] who didn’t have much choice in the matter.

(4) The Caesar Line was the Germans’ last line of defence before Rome, running from Ostia in the west to Pescara in the east. They fell back to a switch line north of Rome when the Allies entered the city in early June 1944.

(5) The next lines of defence were the Trasimene Line (a.k.a. the Albert Line) and the Arno Line, which were mainly used as a stalling device so the Germans could fortify the so-called Gothic Line to the north.

(6) The Gothic Line (a.k.a. the Green Line), roughly from Pisa in the east to Rimini in the west, was the Germans’ last, best hope of containing the Allied march up the Italian peninsula. The Line held throughout the winter of 1944-’45 wasn’t decidedly breached until April 1945.

So German stalling tactics had worked: the Allies never did break out of the Italian peninsula before the end of the war. Which of course should not obscure the fact that the Germans did lose that war. The overall German strategy in Italy was defective, premised on the objective of losing slowly. But in light of their resources, limited by the Soviet attack in the East, and the loss of their Italian ally, this was perhaps the best they could hope for.

Still, losing slowly is nothing to write home about, one might think. But this curious propaganda map does attempt to tout the accumulation of small defeats as some kind of victory: Yes, the Allies are advancing, but a snail could do it quicker!

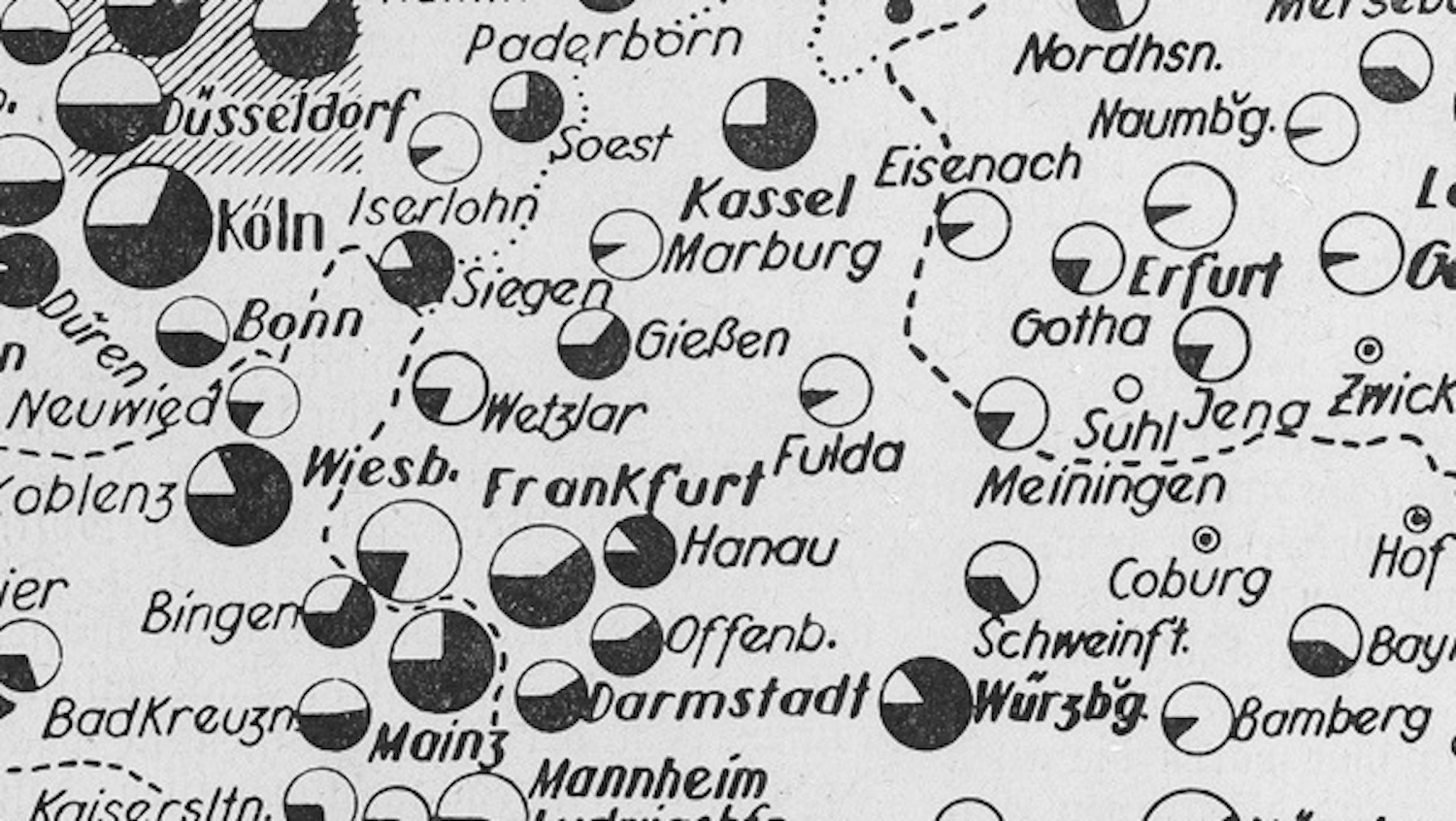

The poster is French [8], except for the title: It’s a Long Way to Rome refers to a marching song popular with British troops in the previous world war [9]. The graph in the bottom left hand corner compares the record de lenteur (speed record) of a snail and of the Allied invader of Italy.

Presuming, as the legend at the bottom says, that the greatest speed achieved by a snail is 0.8 metres (i.e. 80 cm, or 31.5 inches) per minute, that would translate to a distance of 320 km (199 miles) for the period between the start of the invasion (given here as 6 September 1943) and 1 April 1944. In that same time, the Allies only managed to advance 180 km (112 miles), making the snail 1.78 times as fast as the average Anglo-American invader, plodding and slogging along in southern Italy.

The map was designed around the time when the front was still at or near the Gunther Line (see the third dot above). The stalemate at Monte Cassino would soon be followed by an Allied breakthrough, and Rome would fall a mere two months after the supposed publication date of this poster (i.e. 1 April 1944).

Even without the benefit of that hindsight, the concept of an enemy’s slow, inexorable progress seems like a curious, counter-intuitive propaganda tool. Or could it be that desperation in the Axis camp at that point was already so widespread that a slow defeat seemed like the best of all remaining options?

Many thanks to Jim McNeill for sending in this map, found here at the Victoria and Albert Museum collections page.

Strange Maps #599

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

[1] Which is ironic (if that’s not too frivolous a word for such deadly business): Germany’s military strategy for victory in both the First and Second World Wars was based on the Schlieffen Plan – a major element of which was a pincer movement intended swiftly to crush France. See #138 for a map of the plan. ↩

[2] An underground bunker near the Chancellery in Berlin, and the nerve centre and last holdout of the Nazi top cadre during its final months. Hitler committed suicide in the bunker a few days before war’s end, with Soviet troops only a city block away. ↩

[3] Mussolini first called the (then still nascent) alliance between the fascist regimes in Italy and Germany an ‘axis’ in a speech on 1 November 1936, because all other states in Europe would revolve around it. The Axis Rome-Berlin would later also extend to Tokyo, earning the it the nickname Roberto, for the three capitals’ initial letters. Despite the efforts of the Jimi Hendrix Experience (which released Axis: Bold as Love in December 1967), the geopolitical term ‘axis’ hasn’t managed to shake its sinister connotation. That fact was not lost on U.S. president George W. Bush, who in his 2002 State of the Union address labelled Iran, Iraq and North Korea an ‘Axis of Evil’. ↩

[4] The invasion of the mainland had itself been preceded by the relatively easy conquest of Sicily, in the weeks after 10 July 1943. ↩

[5] 320,000 Allied casualties, of which 60,000 fatal; and almost 340,000 Axis casualties, of which 50,000 fatal. ↩

[6] Short for Victory in Europe Day, when the Allies accepted Germany’s unconditional surrender. Soviet and American troops had already met in Central Europe, but some areas remained under effective control of the German military on that day, including small parts of northern Italy. ↩

[7] General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin (1891-1963) was an intriguing figure: a scion of Catholic aristocratic family, a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, a lieutenant in the First World War, a lay member of the Benedictine order, an efficient military commander, and a known sceptic of Nazism. The fact that he managed to evacuate the treasures of Monte Cassino without any of the convoy’s trucks being attacked by the Allies, may result from a tacit gentleman’s agreement between the opposing sides. In 1950, Senger was involved in the Himmeroder Denkschrift, a memorandum that paved the way to (West) German rearmament and the eventual establishment of the Bundeswehr. ↩

[8] Hence probably produced by the so-called Vichy regime, a collaborating entity in the south of France. For another example of an animal-inspired, French-language, pro-German propaganda poster, see the Churchill Octopus mentioned in #521. ↩

[9] It’s a Long Way to Tipperary. ↩