Will Men Ever Learn to Deal With Their Emotions?

In a recent interview, Michael Pollan discusses the inherent feminism of the processed food revolution in midcentury America. Post-war women were accustomed to working, no longer interested in catering to their husbands by cooking and cleaning when they were breadwinning as well.

In his Netflix series, Cooked (based on the book by the same name), Pollan notes that historically, anytime the buck can be passed on meal prep, it is. Cooking is laborious and consuming; the romance of farm to table is only romantic if someone else is serving the table. Enter numerous food companies selling you an aluminum-tray dinner—microwavable brownies colluding with Salisbury steak!

Leaving aside the damaging effects of processed foods, the industry not only alleviated the burden placed on women. It did the same for men. If their wives were not going to make dinner, neither were they. Fast food chains and freezer aisle staples helped men save face.

Pollan argues that the best outcome is to bring everyone back into the kitchen. The barriers to entry are high: time constraints; childcare (though Pollan does mean everyone); women not feeling like they’re being tossed back a half-century; men dealing with preconceived notions of family division.

Of course, this picture is painted with a broad stroke—many men cook. But the emotional aspect of dealing with one’s internal chatter is critical, especially, argues professor Andrew Reiner, when it comes to overturning long-held assumptions. He recently wrote about his history teaching a course in masculinity:

Despite the emergence of the metrosexual and an increase in stay-at-home dads, tough-guy stereotypes die hard. As men continue to fall behind women in college, while outpacing them four to one in the suicide rate, some colleges are waking up to the fact that men may need to be taught to think beyond their own stereotypes.

An emergence of men’s retreats and workshops has steadily increased in the past decade—not exclusive golf or cigar clubs, mind you. Connecting with the inner masculine has been something men of all ages grapple with, though Robert Bly noticed that a moment of reckoning often comes near middle age:

By the time a man is thirty-five he knows that the images of the right man, the tough man, the true man which he received in high school do not work in life. Such a man is open to new visions of what a man is or could be.

What could he be? Reiner notes that having your ‘Man Card’ and believing ‘I got this,’ two stereotypical responses rampant in college life, continue throughout life. In many ways the research showing young boys to be more emotive (while crying more often) than girls perpetuates until the end. We’ve just stubbornly bottled it up, allowing it to fester and spoil, rather than air it out so that frustrations have room to breath.

Like Bly, Michael Meade employs mythology as a foundation for self-understanding. In his book on initiation, he writes that it is the wound in which men discover freedom—a topic long discussed, from Rumi to Joseph Campbell. This method relies on vulnerability and honesty, two qualities associated with being effeminate, and therefore avoided.

The first step is recognizing psychic or emotional pain, rolling it around in your mind, coming to terms with the wound. If you’re avoiding latent issues, it’s impossible to notice the pain in others. Empathy is a crucial step in healing, however. Meade writes,

He’ll only be able to see the wound that secretly troubles him when he puts it into someone else. Then, he’ll feel strangely better for a moment. The old ideas of initiation tried to shape a wound through which each boy could come to know his own wounds and know the ways in which the world wounds everyone.

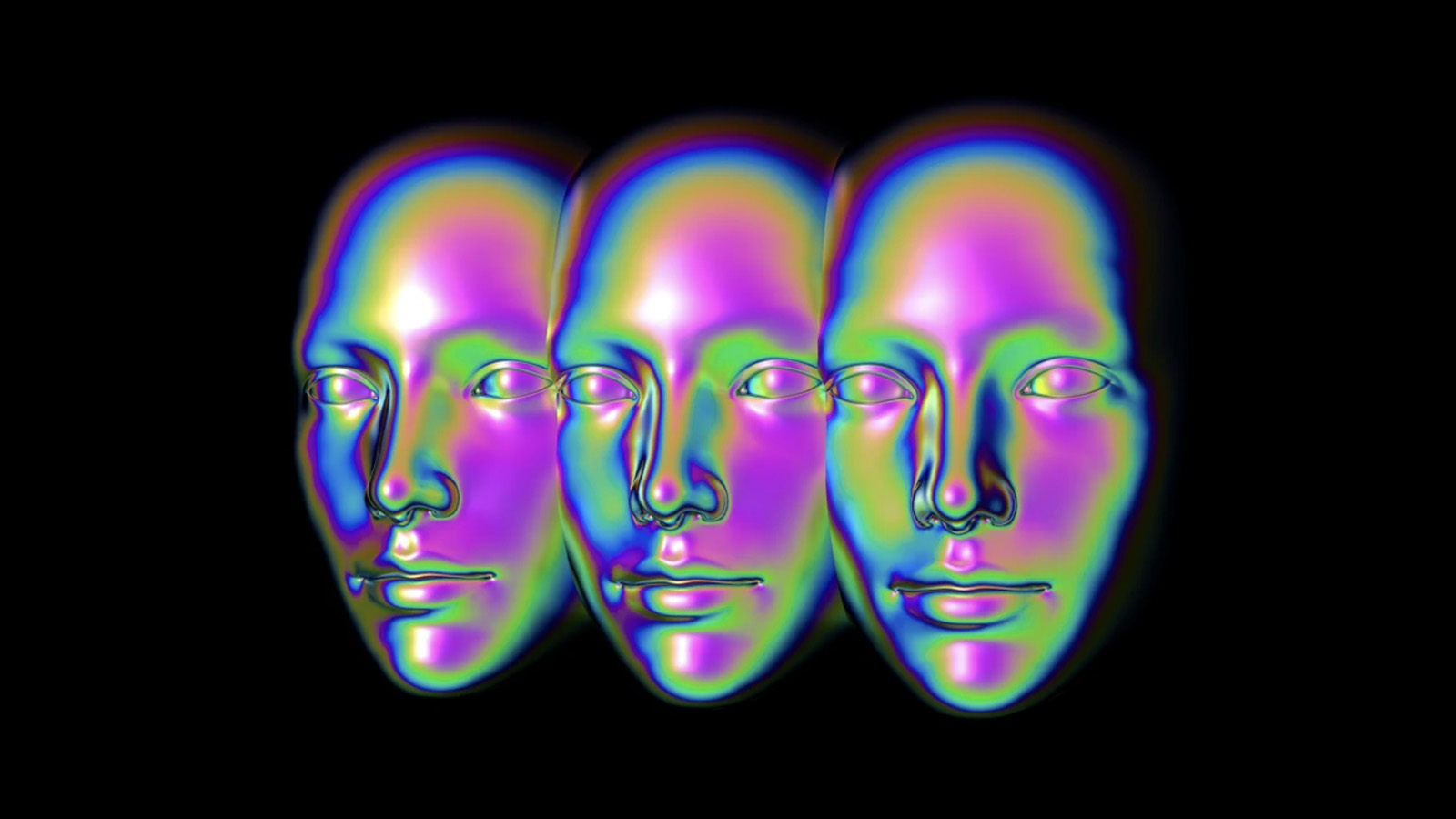

The wound silently undergirds politics today: the fear of losing identity, the notion of racial purity, the quest to prove the other hates women more. An intelligent, nuanced conversation in this polarizing atmosphere proves impossible. Hiding behind a procession of masks is easier than admitting ignorance or uncertainty. There’s a reason one candidate has trumped all others, directly pointing to the high school machismo Reiner discusses.

We’re drawn to power and force even when we lack it—we’re drawn to it precisely because we lack it. Confidence precedes clarity and comfort, for one who is comfortable in their skin accepts and debates criticism without being infuriated by it. Cynicism, snark, anger, vitriol, violence—signs of a deeply unsatisfied being residing behind the façade of insults and rhetoric.

Emotions arise before thought; in fact, many thoughts are translation of emotions, how we feel. How we feel is influenced as much as what we bring to light as what we leave in the darkness. Author David Deida has spent decades inspiring men to reconvene with their emotions. He too is an advocate for male gatherings, so long as intention and purpose is honored:

They are not occasions for lapsing from fullness, but for communing beyond fear…Whatever you do, share as much loving as you can with your friends, without settling for mediocrity or less than each man’s fullest gift.

Reiner concludes with a student admitting a fear “that the natural order of things will completely collapse.” The puffed chest alpha male continues to reign, like a Matryoshka doll. Peel open enough lids and the emptiness is palpable. A sad fate, though not nearly as tragic as never peeling them to begin with.

—

Image: Sascha Steinbach / Getty Images

Derek Beres is a Los-Angeles based author, music producer, and yoga/fitness instructor at Equinox Fitness. Stay in touch @derekberes.