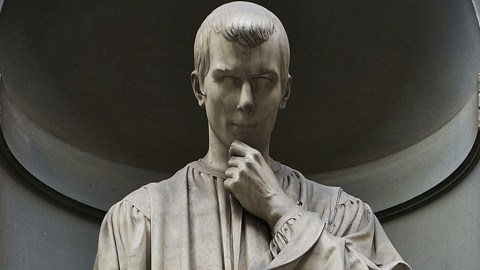

The Prince: Why One of the Most Hated Books in History Still Matters

When you think of classic books, you probably think of books that are two hundred years old at most. Hugo, Dickens, Austen, Twain, Shelly, and so on. The great works of Shakespeare being the oldest literature that most people ever really read, outside of religious texts. But one work of Renaissance literature in Italy still stands out as one of the most important books ever written, and still strikes us with an uncanny feeling of understanding and dread when we think of it; The Prince, by Machiavelli.

Few books have garnered as much controversy during their existence as The Prince. It has been banned by the Catholic Church, seen as cynical by many, and was the basis for the naming of one of the worst psychological traits a person can have-Machiavellianism. This is the book that gave us such quotes as “It is better to be feared than loved, if you cannot have both”, and “The ends justify the means”. History’s greatest how-to-rule guide has also been one of the most widely reviled books of all time.

And the worst part? This book is still incredibly relevant to us today.

The book begins by telling us that it is about how to run (specifically) an Italian renaissance autocracy in the same way that the (irony alert) ever relevant Art of War pertains to iron age warfare. While several portions of the book, such as the section discussing the proper ratio of local troops and mercenaries to build an army with are relics of times past, The Prince still offers us practical lessons in politics today.

While some of the best ideas in the book can seem obvious, like that a council of advisers should be wise men rather than flatterers; many people still don’t follow the advice. Before Machiavelli, many of the big ideas he wrote about weren’t even well agreed to.

Here are a few of the ideas that can be used, for good or evil, laid out by Machiavelli.

“A prudent man should always follow in the path trodden by great men and imitate those who are most excellent.”

“It is essential therefore for a prince to have learnt how to be other than good and to use, or not to use, his goodness as necessity requires.”

“All courses of action are risky, so prudence is not in avoiding danger (it’s impossible), but calculating risk and acting decisively. Make mistakes of ambition and not mistakes of sloth. Develop the strength to do bold things, not the strength to suffer.”

“Be it known, then, that there are two ways of contending, one in accordance with the laws, the other by force; the first of which is proper to men, the second to beasts. But since the first method is often ineffectual, it becomes necessary to resort to the second.”

“And here we must observe that men must either be flattered or crushed; for they will revenge themselves for slight wrongs, whilst for grave ones they cannot. The injury therefore that you do to a man should be such that you need not fear his revenge.”

As you can see, many of the pieces of advice in the book are benign or even admirable. Most of them, however, suggest that a wise leader tend to healthy doses of brutality, suppression, and nighttime raids as needed. An idea that offends those of us who suppose that a righteous leader will always prevail in the end. It is that very idealism we love that The Prince warns us against.

While we might want our leaders to be Christlike or be the kind of guy we would want to have a beer with, Machiavelli points out that what we really need is effectiveness. The things that make a person nice are rarely the things that make a politician effective. A detail which is relevant not only to the petty tyrant, but also to the voter.

Machiavelli had written extensively on republics before writing The Prince, and was held by many Enlightenment philosophers to be a closet republican. Rousseau went so far as to suppose The Prince was a satire on how brutal autocracy can be. In all likelihood, however, The Prince is a sincere how to guide on bringing wealth, glory, and stability to the state, by any means necessary. No matter what the author truly felt about the best way to run a country.

But, if it has all these useful tips, why do we dislike it so much?

Victor Hugo may have summed up our distaste for The Prince best in Les Miserables:

“Machiavelli is not an evil genius, nor a demon, nor a miserable and cowardly writer; he is nothing but the fact. And he is not only the Italian fact; he is the European fact, the fact of the sixteenth century.”

We dislike him because he told us that our politicians cannot all be saints, if any of them can be. We know that Richard Nixon was both unscrupulous and effective, while our sense of justice tells us it shouldn’t be so. Machiavelli’s The Prince reminds us to focus on the real, understand that the virtuous politician is not the same as a saint by any measure, and that it is better to be feared than loved not only for kings, but also for political books.