There Are “Two Halves” To Great Design, Says iPod Co-Designer

Posting and discussing examples of bad design has recently become a curiously popular online hobby. The subreddit r/crappydesign, perhaps the mecca of ridiculing design faux pas, boasts nearly 700,000 subscribers and features posts like an elevator with completely unordered buttons and a height chart that’s placed several feet off the ground. (r/crappydesign’s motto, for the record, is: “MAY THE COMIC SANS AND LENS FLARES FLOW UNFILTERED}”.)

The cringeworthy design flaws of r/crappydesign are obvious. But what about the subtler forms of bad design, like those annoying little stickers grocery stores put on fruit?

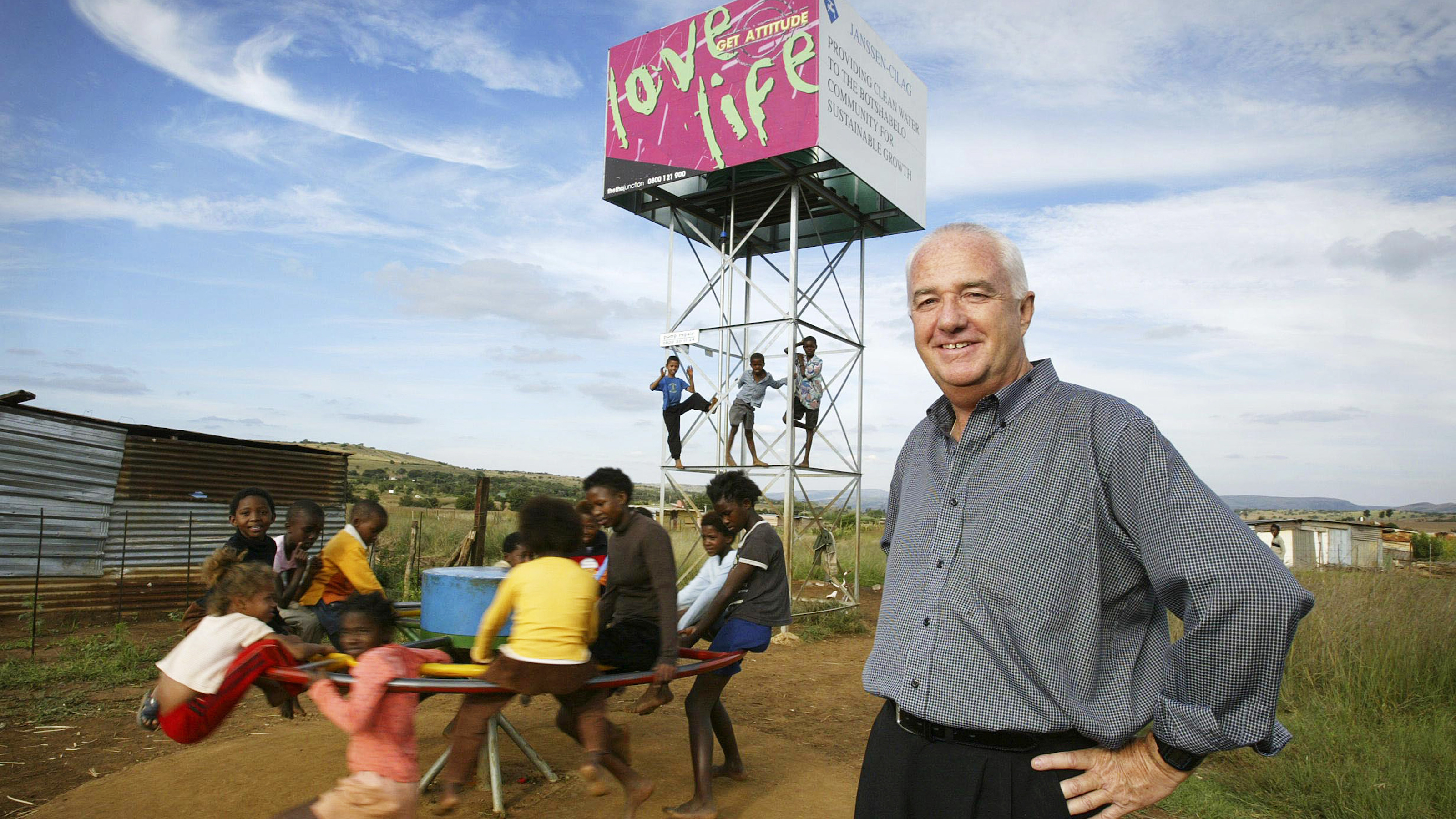

r/crappydesign submission from Xadacka

These are the flaws that Tony Fadell, the designer who led the team that developed the first generations of the iPod, can’t help but notice. In an interview featured on the TED Radio Hour, Fadell and host Guy Raz discussed how easy it is to overlook them throughout the day:

“The fact that we accept [them] – it makes me think that we’re just drones,” said Raz. “We’re just sheep. We just go through our lives and the world just accepting so many of these design flaws that actually don’t improve our lives.”

The good news? Fadell thinks that while some great designers are naturally gifted, others have learned to create innovative and useful designs through simple hard work.

“It just takes practice,” he said. “Just like learning the piano, some people have incredible talent. But you can still learn to play the piano. And I think design is the same way if you set your mind to it. So no one should ever think that there’s this ‘whoa’ incredible design person, and that we have to go to the oracle for all design. No, you can do it yourself.”

Fine-tuning your eye for design, Fadell says, requires attention to detail. It’s a matter of putting a magnifying glass up to the ways in which you interact with products and infrastructure, and asking yourself how they could be better – practically, aesthetically, or even emotionally.

In fact, emotion plays a central role in Fadell’s product design philosophy. The products that succeed, he argues, strike a perfect balance between rational appeal and real emotional experience. He thinks this explains why some well-constructed products, like Microsoft’s Zune, die out:

“So this is a thing that I’ve been wrestling with with my, you know, 25, 30-year career. And I think I figured it out. And what you always have to look at is when you design something, there are two halves to design, just like there’s two halves to your brain – the emotional part and the rational part.

And you need to separate your features into both the rational features that cause people to want to buy it and the emotional features that get people off their duff to actually buy it. So you have to blend these two halves in a very good blend to be able to get people excited and off their butt to go and buy it because they see value beyond the sexiness.”

The idea that emotions play a part in product design is nothing new. But Fadell frames it in terms of something he calls emotional momentum:

From the time you first learn about a product, you engage with that. And then you learn more and more about it if it’s intriguing to you. And you hope that there’s this positive emotional momentum that builds on itself at each step of the process.

Design flaws, however, can stop that emotional momentum in its tracks.

For example, say you’ve been patiently awaiting the release of a new electronic gadget. The day comes when it hits the stores and you rush to buy one. You drive home, excited to finally play with it. But when you open the package you find the gadget’s battery is dead and you have to wait an hour for it to charge.

“…that causes you to hit a brick wall. And you lose all the momentum. People are like oh, I’m frustrated. You just threw away this entire great experience you were designing for people.”

In the 1990s, Apple noticed this problem and started delivering all of its products at least partially charged. The result? Every other tech company eventually followed suit.

You can listen to more of Fadell’s interview below: