In Papua New Guinea, “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels” turned the tide of WWII

- During the Second World War, native Papuans helped Australian soldiers fight the Japanese.

- Affectionately known as “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels,” they often helped wounded soldiers back to camp.

- But the rose-colored legacy of the angels detracts from their mistreatment.

“Many a lad will see his mother and husbands see their wives / Just because the fuzzy wuzzy carried them to save their lives / From mortar bombs and machine gun fire or chance surprise attacks / To the safety and the care of doctors at the bottom of the track.”

This is an excerpt from a poem written by Sapper Bert Beros, a Canadian immigrant serving in the Australian army during the Second World War. Beros wrote the poem while stationed at the Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea, where the Australians enlisted the help of natives to prevent the Japanese from seizing the capital city of Port Moresby.

The Papuans’ familiarity with the dense, hard-to-navigate terrain made them an invaluable asset. Rather than fight, they assisted the Australians by transporting supplies, spying on the enemy, and — as famously described by Beros — carrying wounded soldiers back to safety.

The poem, published in the Brisbane Courier-Mail after a fellow officer mailed a copy to his mother, epitomizes Australia’s gratitude for and admiration of the Papuans: the “Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels,” as Beros affectionately called them, after the texture of their hair. At the same time, and especially today, this romanticized depiction of the Papua New Guinea natives distracts from their mistreatment during the war.

Although the Papuans were called Angels, in reality, they were more like slaves, conscripted into the conflict against their will by a country that saw them as second-class citizens.

Life on the Kokoda Track

The Second World War played out in two theaters: West and East. Just as Nazi Germany sought to subjugate the nations of Europe, so did Imperial Japan try to colonize East Asia. Control of Papua New Guinea’s Port Moresby was a top priority for the Japanese, not only because it would expand their influence over the Coral Sea, but also because it would allow them to disrupt communications between Australia and the United States. Between July 21 and November 16, 1942, the Australians were able to halt Japan’s advance and expel the enemy from the island — but not without help from the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels.

War turned the world of the Papuans upside down. Prior to the Japanese invasion, many villages along the Kokoda Track — a small, mountainous road that runs from Port Moresby in the south to Buna in the north — lived a traditional existence interrupted only by occasional visits from Australian patrol guards. If developed countries had underestimated the destructiveness of modern warfare, the Papuans had no idea what was coming.

“The Japanese dropped a bomb and started to fight with the Australian Army,” Ovuru Indiki, a Papuan who grew up during the campaign, told the Kokoda Historical Society. “The Japanese dropped more and more bombs. So I ran away from Port Moresby to Naduri. The fighting damaged all of our food gardens for the village people of Kagi and Naduri. We had no money. It took hard work, at a bad time. I keep the medal for my father now. 1942-1945 is a bad time.”

Although the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels were victims of Japanese aggression, they did not willingly enlist in the Australian army. Conscription began in June 1942, when the Australian Major General Basil Morris issued an “Employment of Natives Order,” and lasted three years. An estimated 16,000 Papuans were recruited. Some were forced while others were lured with unkept promises of shorter service and improved working conditions.

The type of work they received was predicated on their knowledge of Papua New Guinea’s wild, mazelike terrain. Some acted as scouts, venturing into Japanese territory to gain intelligence on their activities and movements. Others carried arms and provisions to and from the front lines and helped the sick and wounded get back to the Australian base at Ower’s Corner. While the first and second of these responsibilities were arguably more important to the war effort, it is carrying wounded soldiers for which the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels are most often remembered today. Without them, as Beros had rightfully noted, many Australians back home would have ended up as orphans and widows.

The truth about the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels

“The popularity of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angel,” writes historian Lachlan Grant “overshadows the insidious face of colonialism also evident within the New Guinea campaign.” Fellow historian Liz Reed agrees, adding the treatment and subsequent portrayal of the native Papuans by Australians has “placed them within a colonist construct,” and that, during the Pacific War, “negative stereotypes and disparaging attitudes justified exploitative recruitment, negation of indigenous agency, poor working conditions, inadequate compensation, and casual abuse.” Their research shows that employees of the Australian New Guinea Administration Unit or ANGAU, in charge of recruiting the Papuans, often referred to themselves as the “white masters,” or taubada, while the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels were treated as inferior “others,” second-class citizens supposedly lacking in civilization.

Studying the wartime experiences of the Papuans has proven challenging, not only because they left no written records — oral testimonies by Indiki and others are the rare exception — but also because many Australian war correspondents were unable to report on the true conditions of the campaign due to censorship rules instated by US General Douglas MacArthur. Still, censorship is but one part of the explanation, with the other concerning race relations in the Pacific. Instead of learning their names, Australian officers tended to refer to enlisted Papua New Guinea natives using generic terms, making it difficult to locate the people described in their written accounts.

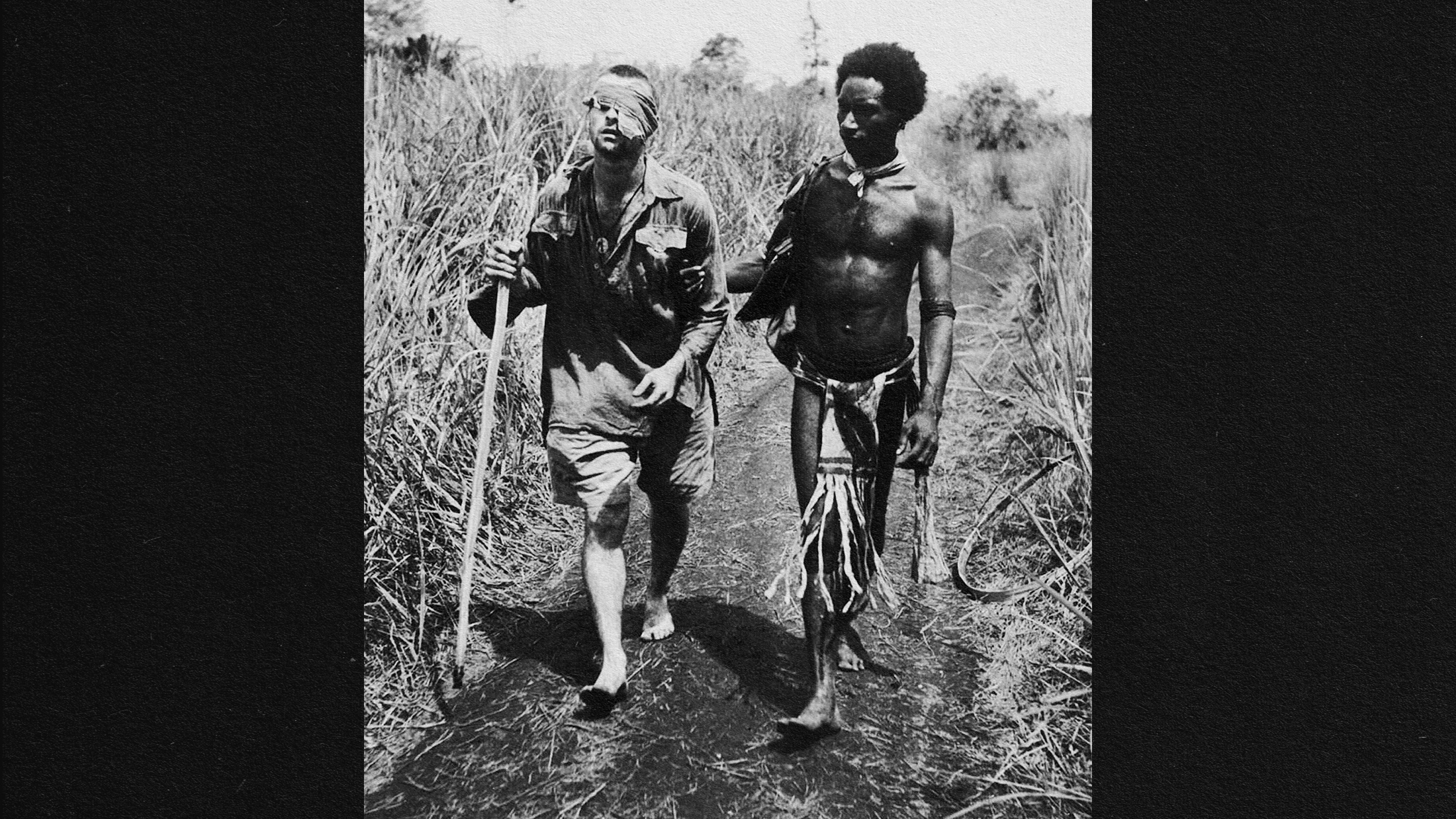

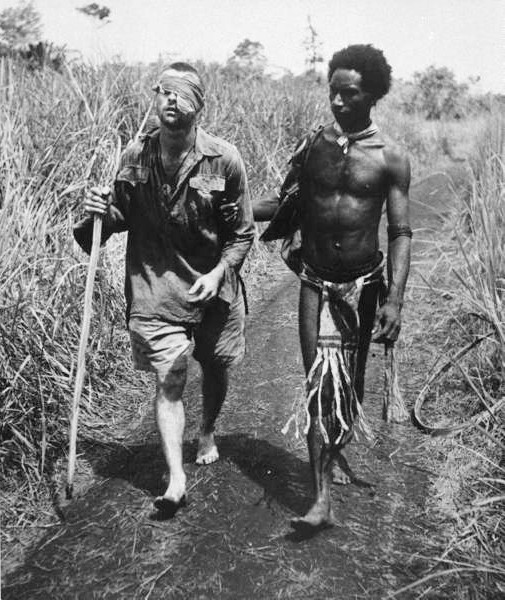

This difficulty was illustrated by the search for the native Raphael Oimbari, who appears front and center in a famous wartime photograph guiding a blinded Australian private through a field. While the private, George Whittington, was quickly identified, it took several decades to learn the name of his savior.

Another illustration of the relationship between Australians and Papuans comes from war correspondent Raymond Paull. Paull recounts a day in the campaign when a senior medical officer ordered 140 natives to bring their stretchers to the town of Alola. The natives went, only to be turned away by soldiers stationed down the road. They then passed the medical officer on their way back to the base, but the medical officer did not recognize them; only when he had reached Alola and found nobody did he realize he had walked past his own men. The sad moral of this story, wrote Paull, is that “to the Australians, all the natives looked much alike.”

To top it all off, Australian soldiers on the Kokoda Track campaign were even given military handbooks on how to interact with the Papuans. The following passage speaks for itself:

“It is not too much to say that … [the native] stands in awe of us. He thinks we are superior beings. We may not all deserve this reputation, but it is worth acting up to.”

As does this one:

“Always, without overdoing it, be the master. The time may come when you will want a native to obey you. He won’t obey you if you have been in the habit of treating him as an equal.”

Memories of war

Even positive depictions of the Papuans, such as Beros’ poem, reflect colonial attitudes. The poem speaks of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels “Bringing back the badly wounded just as steady as a horse / Using leaves to keep the rain off and as gentle as a nurse,” equating them with servants and service animals.

After the war, Beros’ language was taken over by the Australian public, who praised the Papuans for their “uncomplaining and lion-hearted endurance.” These descriptions, noted a reporter from the Cairns Post, make it seem as though, in the eyes of the average Australian, the savages, having proven themselves, “suddenly [became] real and courageous, and very remarkable human beings.”

Far from elevating the social status of Papuans, the Kokoda Track campaign only served to prolong colonial relationships between the two countries, with many natives of Papua New Guinea living in or near Australia struggling to achieve the same opportunities and quality of life as their white neighbors.