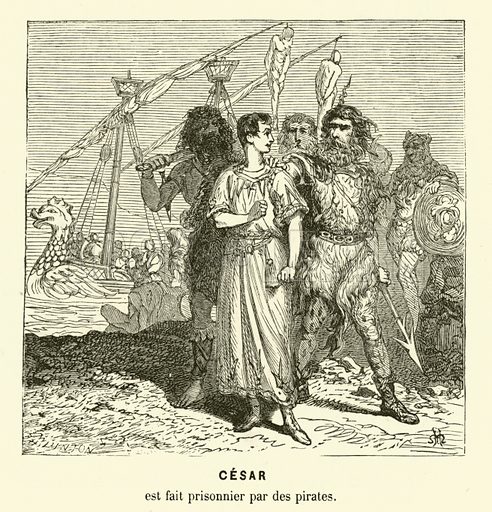

Julius Caesar was once captured by pirates. Then he got revenge.

- The 25-year-old Caesar treated his captors like his personal underlings.

- After being released, the future dictator hunted down the pirates and crucified them.

- Though (probably) part propaganda, the story foreshadows the future that awaited Caesar.

Before Gaius Julius Caesar conquered Gaul, crossed the Rubicon, and laid the foundation for his adopted son Octavian Augustus to turn ancient Rome from a republic into an empire, he was just another affluent patrician looking to make a name for himself in the Roman bureaucracy.

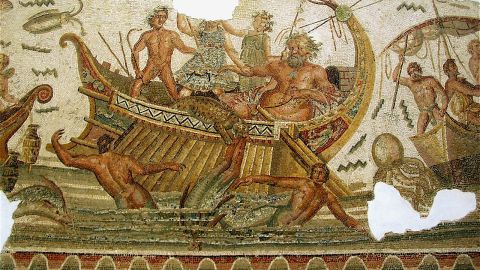

His ambition led him across the known world, from the shores of Spain to the mountaintops of Asia Minor. On one of these trips, while crossing the Aegean Sea, a 25-year-old and still-untested Caesar found himself captured by Cilician pirates. Far from stopping him in his tracks, however, the pirates were among the first to learn just what the future dictator was made of.

I came, I saw, I got captured

Although historians agree Julius Caesar was captured, they disagree on the place and time. Three Roman authors — Valerius Maximus, Aurelius Victor, and Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus — date the encounter with the pirates to 75 or 74 BC, when Caesar was on a trip to Rhodes. The historian Plutarch says it happened earlier, in 80 BC, after Caesar had visited King Nicomedes of Bithynia, a kingdom located in present-day Turkey. A fifth source, Polyaenus of Greece, claims he was captured before the visit, not after.

Of all these dates, the one provided by Polyaenus is the most convincing. As the historian Allen M. Ward points out, Caesar was on his way to Turkey to procure ships for his commander, Marcus Minucius Thermus. The purpose of this journey was probably not — as Plutarch had supposed — to escape Rome’s current ruler, Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix, who was at war with none other than Caesar’s uncle, Gaius Marius. “It is not likely that the pirates would have captured him as he was returning in force with a fleet in 80,” Ward writes, “but rather as he set out on his mission to Bithynia in 81.”

The details of Caesar’s captivity are slightly less ambiguous. Taken prisoner off the coast of Lesbos, Suetonius says he was held for “nearly forty days.” Unfortunately for his captors, Caesar proved to be a terrible prisoner. At night, he demanded the pirates keep their voices down so he could sleep. During the day, he forced them to listen to the poems and speeches he composed to stave off boredom. He even took issue with his own ransom. According to Plutarch, Caesar felt the 20 talents of silver the pirates wanted in exchange for his release (circa 620 kilograms or $600,000) was too low for someone of his caliber. He urged them to ask for at least 50.

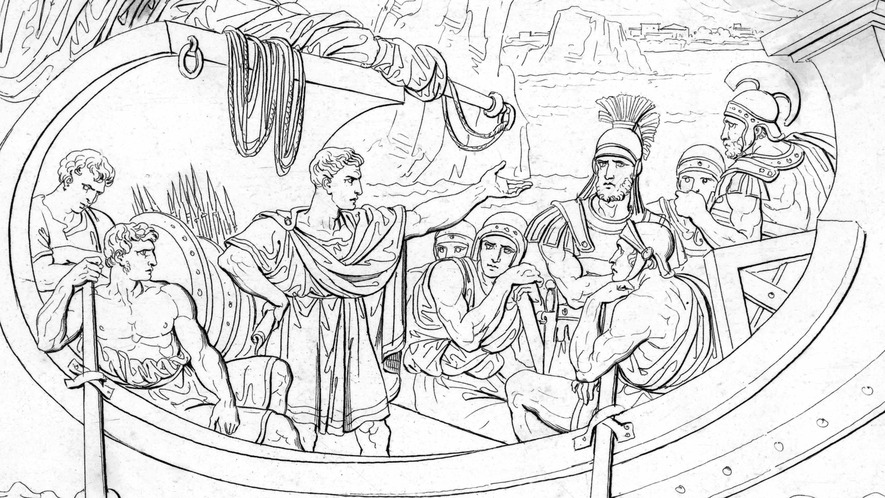

Caesar’s release and subsequent response are again debated. The most colorful account (from Polyaenus) holds that Caesar — who, in spite of his annoying demands and threats of retribution, had actually grown quite close to the pirates — invited them to a banquet, drugging their wine and killing them in their sleep. Ward suggests this outlandish version of events might have originated from the name of the island where Caesar is thought to have been held, Pharmacusa, its name related the Latin word for “drug.”

While Plutarch may have been wrong about when Julius Caesar was captured, Ward believes he was right about what happened after he was set free. Instead of channeling his inner Odysseus (or Aeneas), Plutarch says that Caesar used the fleet he received from King Nicomedes to pursue the pirates, take back his 50 talents, and bring them before Marcus Junius Juncus, the governor of Asia. When Juncus decided to sell the pirates into slavery, Caesar — making good on his threats — crucified them before the order could be processed.

The birth of Caesar

The story of Julius Caesar’s kidnapping is somewhat unique in ancient history as historians from this time period devoted more time and energy to chronicling the adulthood of important figures than they did their youth. As such, the kidnapping represents a rare entry into Caesar’s early biography — a biography that pays relatively little attention to the work he did as a military tribune or the extent to which he helped stop the slave uprising of Spartacus, two of the arguably more important chapters of his life.

Still, this story, however fascinating, should not be taken at face value. After all, as Josiah Osgood, a professor of classics at Georgetown University, states in an article, “It could easily lend itself to embellishment, even outright rewriting.” Some writers may have rewritten the narrative to portray Caesar in a negative or positive light: Valerius Maximus, an early authority, stressed Caesar’s virtues, lamenting how “fortune willed that for a small sum [of 50 talents] the brightest star in the universe should be exchanged in a pirate galley.”

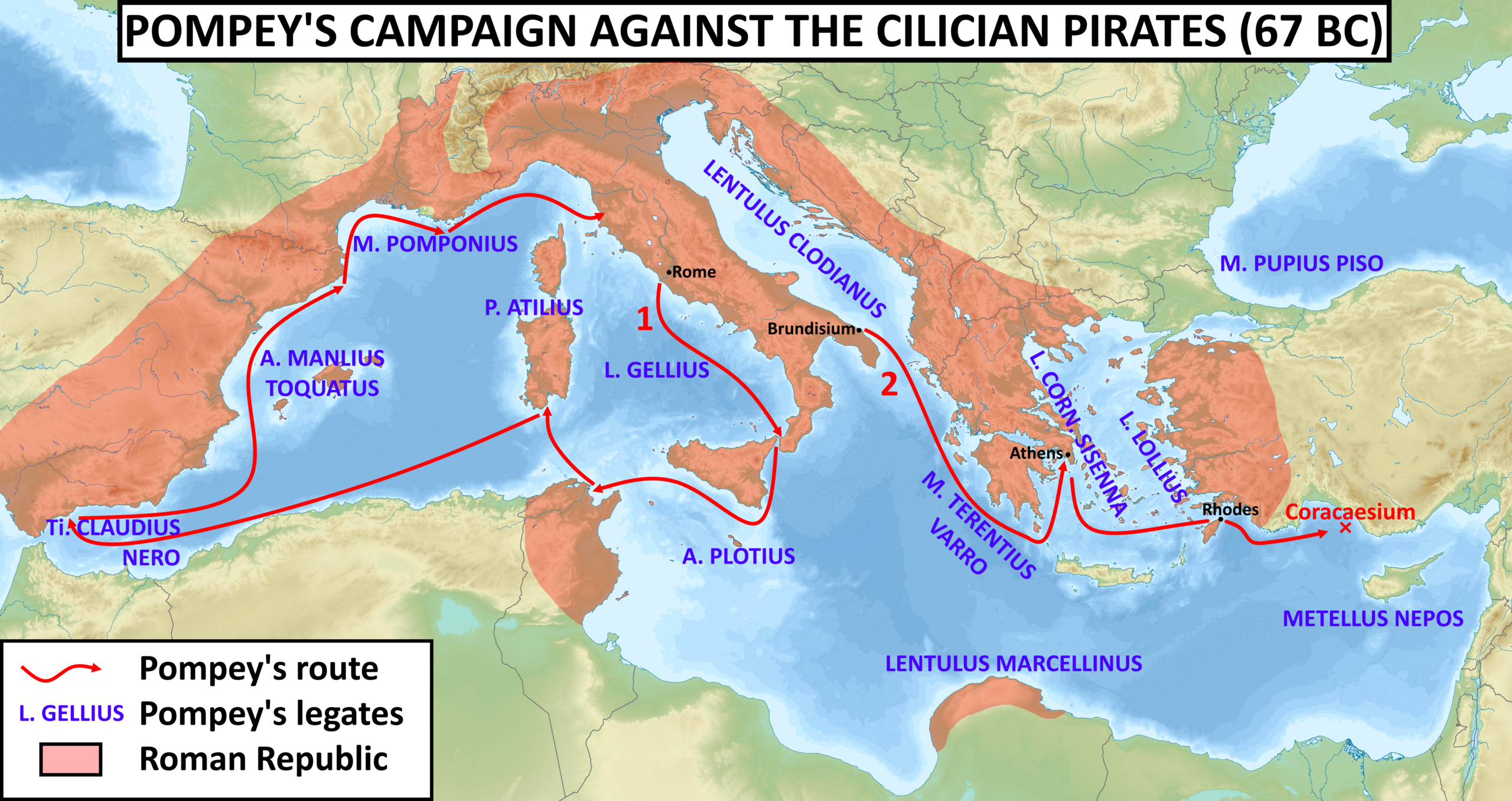

Some rewrites may be traced back to Caesar himself, who — as the episode’s one and only witness — could have easily made himself seem braver or more ruthless in order to advance his own political career. The earliest and by now long-lost sources on which the accounts of Plutarch and Suetonius have been based were written by people who had known Caesar personally, such as his close friend, Gaius Oppius. Osgood even indicates Caesar recounted the story on the Senate floor to convince his colleagues to authorize Pompey the Great to eradicate Mediterranean piracy — a motion he alone supported, but which was ultimately granted.

Although the story of Julius Caesar’s kidnapping no doubt contains hints of propaganda and self-promotion, it also functions, albeit retrospectively, as a moment of foreshadowing. It’s an early demonstration of everything the future dictator turned out to be capable of: audacity, confidence, and self-sufficiency. The young Caesar captured by pirates exhibits the same qualities the elder Caesar exhibited when he took over Rome. What’s more, both the pirates and the Roman Republic underestimated Caesar, each failing to see — as Plutarch once put it — the “powerful character hidden beneath his kindly and cheerful exterior.” The pirates paid for this mistake with their lives, the republicans with their government…and then their lives, too.