How a huge, underwater wall could save melting Antarctic glaciers

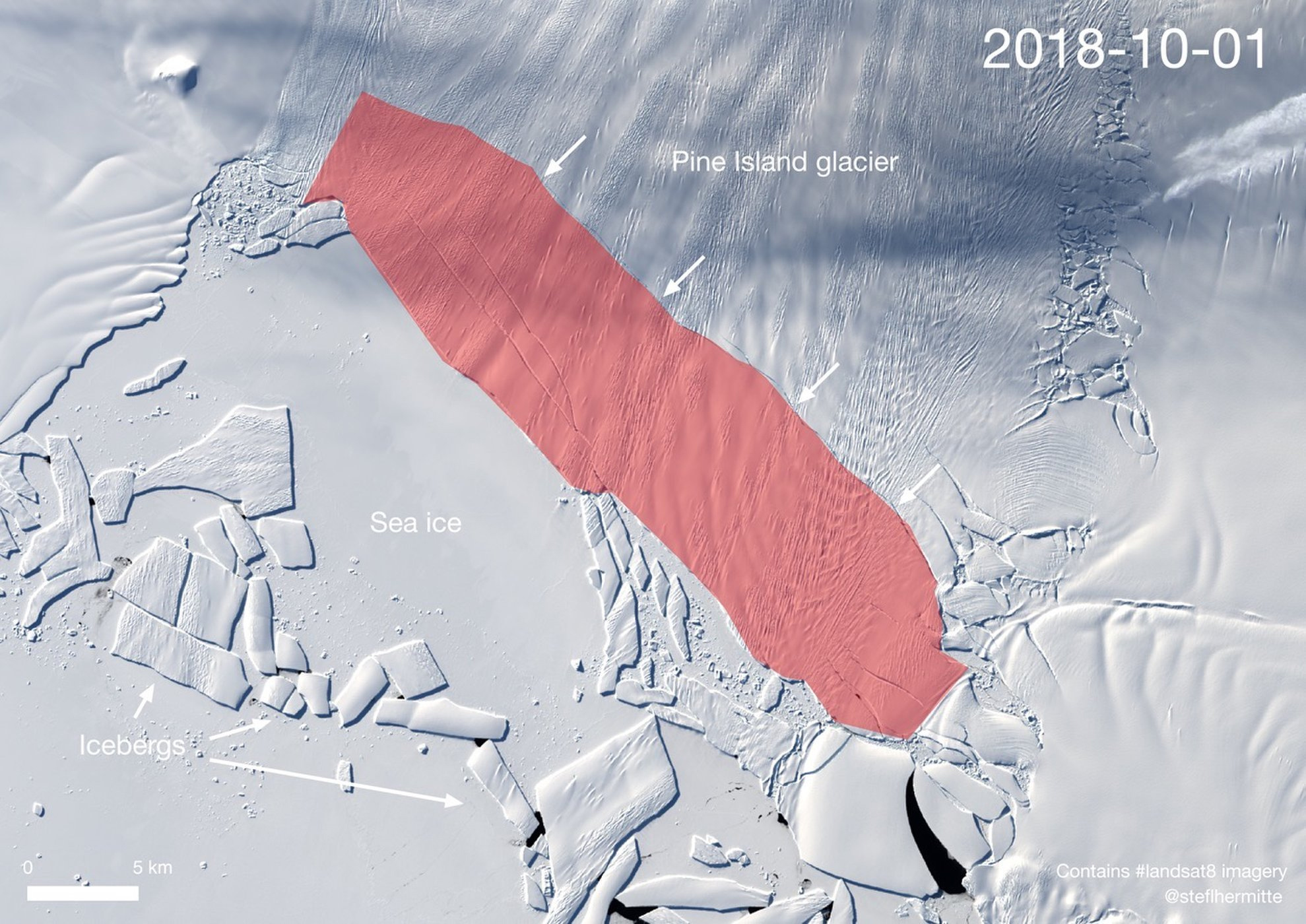

Image: NASA

- Rising ocean levels are a serious threat to coastal regions around the globe.

- Scientists have proposed large-scale geoengineering projects that would prevent ice shelves from melting.

- The most successful solution proposed would be a miles-long, incredibly tall underwater wall at the edge of the ice shelves.

The world’s oceans will rise significantly over the next century if the massive ice shelves connected to Antarctica begin to fail as a result of global warming.

To prevent or hold off such a catastrophe, a team of scientists recently proposed a radical plan: build underwater walls that would either support the ice or protect it from warm waters.

In a paper published in The Cryosphere, Michael Wolovick and John Moore from Princeton and the Beijing Normal University, respectively, outlined several “targeted geoengineering” solutions that could help prevent the melting of western Antarctica’s Florida-sized Thwaites Glacier, whose melting waters are projected to be the largest source of sea-level rise in the foreseeable future.

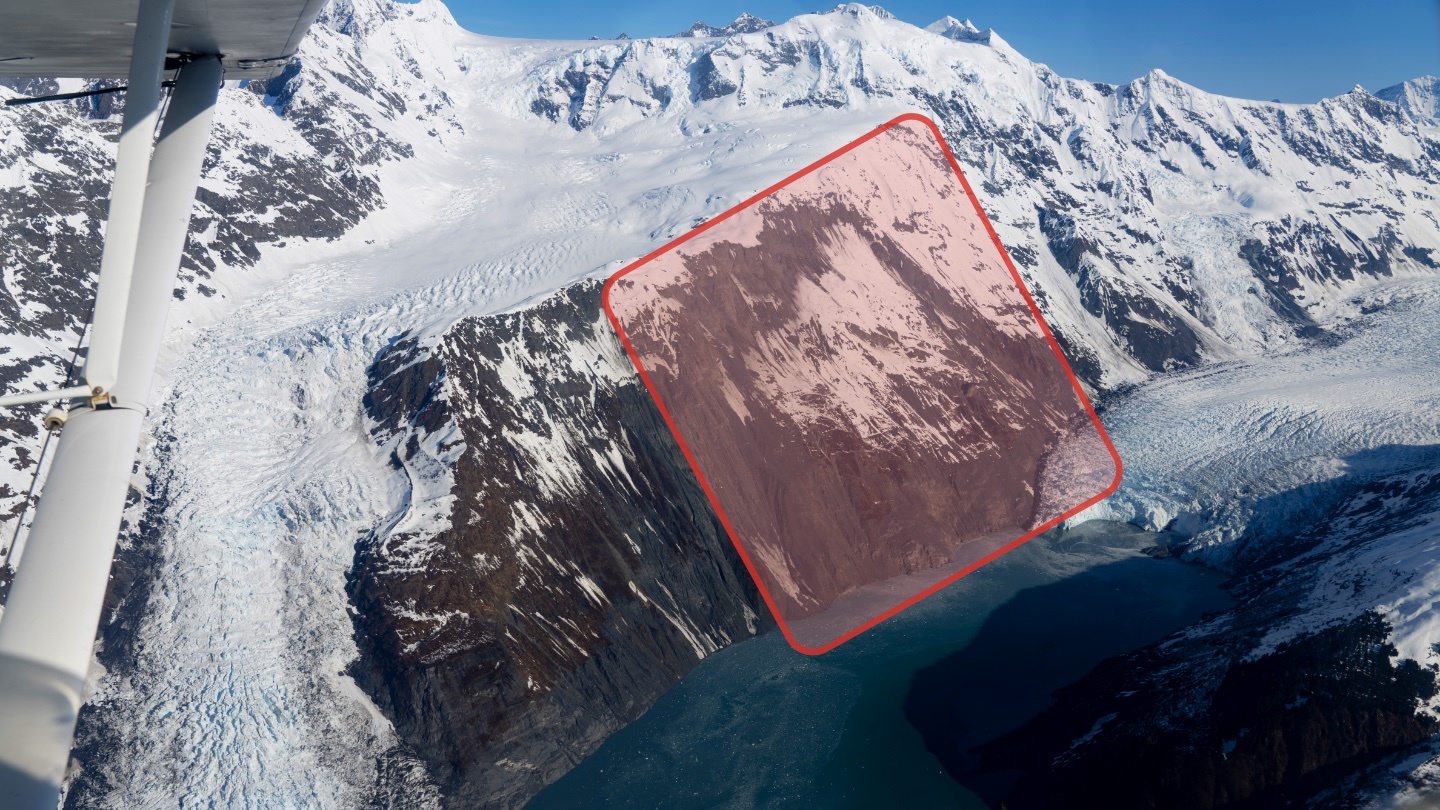

An example of the proposed geoengineering project. By blocking off the warm water that would otherwise eat away at the glacier’s base, further sea level rise might be preventable.

Source: Wolovick et al.

An “unthinkable” engineering project

“If [glacial geoengineering] works there then we would expect it to work on less challenging glaciers as well,” the authors wrote in the study.

One approach involves using sand or gravel to build artificial mounds on the seafloor that would help support the glacier and hopefully allow it to regrow. In another strategy, an underwater wall would be built to prevent warm waters from eating away at the glacier’s base.

The most effective design, according to the team’s computer simulations, would be a miles-long and very tall wall, or “artificial sill,” that serves as a “continuous barrier” across the length of the glacier, providing it both physical support and protection from warm waters. Although the study authors suggested this option is currently beyond any engineering feat humans have attempted, it was shown to be the most effective solution in preventing the glacier from collapsing.

But other, more feasible options could also be effective. For example, building a smaller wall that blocks about 50% of warm water from reaching the glacier would have about a 70% chance of preventing a runaway collapse, while constructing a series of isolated, 1,000-foot-tall columns on the seafloor as supports had about a 30% chance of success.

Still, the authors note that the frigid waters of the Antarctica present unprecedently challenging conditions for such an ambitious geoengineering project. They were also sure to caution that their encouraging results shouldn’t be seen as reasons to neglect other measures that would cut global emissions or otherwise combat climate change.

“There are dishonest elements of society that will try to use our research to argue against the necessity of emissions’ reductions. Our research does not in any way support that interpretation,” they wrote.

“The more carbon we emit, the less likely it becomes that the ice sheets will survive in the long term at anything close to their present volume.”

A 2015 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine illustrates the potentially devastating effects of ice-shelf melting in western Antarctica.

“As the oceans and atmosphere warm, melting of ice shelves in key areas around the edges of the Antarctic ice sheet could trigger a runaway collapse process known as Marine Ice Sheet Instability. If this were to occur, the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) could potentially contribute 2 to 4 meters (6.5 to 13 feet) of global sea level rise within just a few centuries.”