The thin line between conspiracy theories and cult worship is dissolving

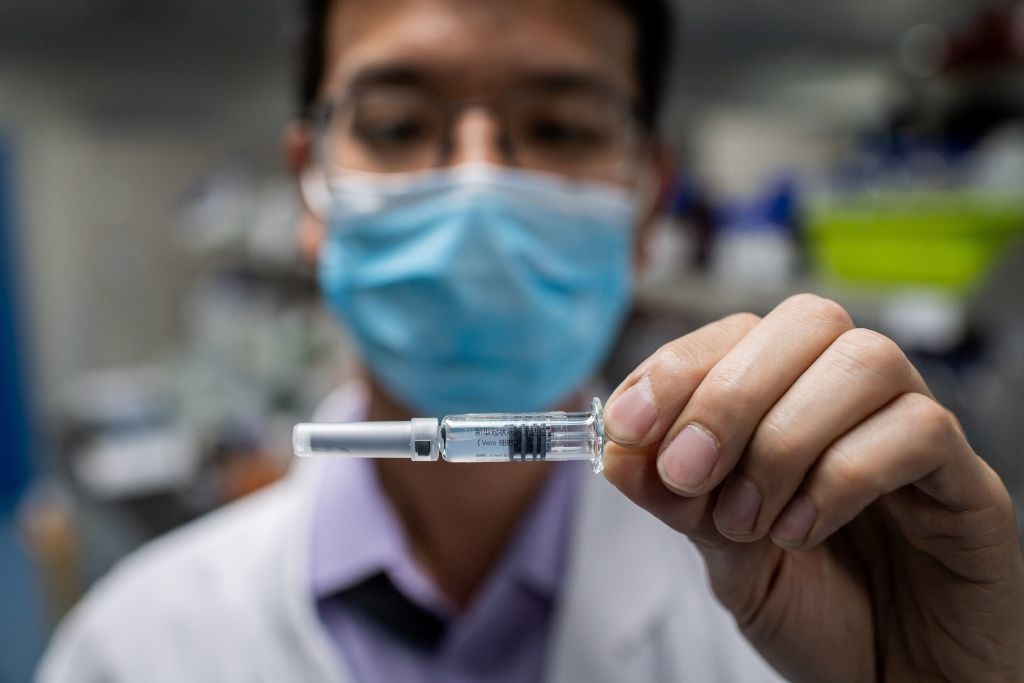

Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images

- Fans of the conspiracy video, “Plandemic,” are exhibiting patterns similar to cult worshippers.

- Conspiracy theories increase during times of social uncertainty and trauma.

- One researcher says conspiracists are more likely to assess nonsensical statements as “profound.”

Birtherism almost seems quaint now. The idea that an American citizen was born in Kenya was never about substance, however. There was no actual debate. As journalist Adam Serwer points out, “Birtherism was, from the beginning, an answer looking for a question to justify itself.”

Logic is detrimental to a conspiracist. Facts impede the narrative. If following the thin threads holding birtherism together is too challenging, don’t be concerned; That’s part of the design. Replace “birtherism” with “Obamagate.” Truth is always a sacrificial lamb to power. Whether circulating from the top or bubbling up from down below, conspiracies are about power.

Yet conspiracy theories are a biological inheritance. We will never live without them. Our brain fills in gaps when no evidence is present. As Australian psychologist Stephan Lewandowsky points out, anti-Semitic conspiracy theories were rampant during the bubonic plague.

Trauma accelerate this process. Within two weeks 100,000 Americans will have died from COVID-19. Social media seems uniquely designed to spread misinformation. This collective trauma has fueled a strange marriage of vaccination fears, 5G, Bill Gates, Anthony Fauci, Big Brother, anti-Chinese propaganda, and more. Weaving a coherent narrative is exhausting (and impossible). A common refrain appears: It’s a power grab.

Discussing the conspiracy du jour that is “Plandemic,” Lewandowsky says contradiction is no barrier to entry:

“Conspiracy theorists may also simultaneously believe things that are contradictory. In the ‘Plandemic’ video, for example, they say COVID-19 both came from a Wuhan lab and that we’re all infected with the disease from vaccinations. They’re making both claims, and they don’t hang together.”

Conditions fomenting the conspiracist mindset are debatable. One 2017 study from Union College speculates that the “constellation of personality characteristics collectively referred to as ‘schizotypy'” provide the building blocks for conspiracist thinking. While not a clinical diagnosis, lead researcher Josh Hart notes conspiracists are more likely to assess nonsensical statements as “profound.” Convincing the converted otherwise is daunting.

How skepticism can fight radicalism, conspiracy theorists, and Holocaust deniers | Michael Shermerwww.youtube.com

To better understand this mindset we should consider cult worship. My first regular writing beat was as the religion columnist for The Daily Targum. While studying for a degree in religion in the nineties, I interviewed clergy, professors, and students from various faith organizations on the Rutgers campuses. I was struck by how adamantly many believed their position to be right. On rare occasions some expressed humility. Certainty is more likely to gain followers.

These interviews led to my fascination with cults. As with conspiracists, cult worshippers suspend disbelief even when not in their best interest. Their buy-in depends upon a counter-narrative promulgated by a leader: Out there the powers that be are trying to hurt you. You’re safe here. Only I can fix this.

Cult leaders exploit anxiety around a shadowy “other” out to get you. While not required, sometimes this other has a form. Ambiguity is a key feature of indoctrination. Diana Alstad and Joel Kramer break this down in their 1993 book, The Guru Papers: Makes of Authoritarian Power.

“What really matters is not so much the specific content of a religion, but how sure one is of its worldview. That is, it’s not nearly as important how true or false a belief is as how certain one is of it. All religious certainty is similar in that the beliefs one is certain of coat and comfort fear.”

Replace “religion” with “anti-vaccination agenda.”

While “Plandemic” seemed to explode out of nowhere, a sophisticated social media campaign created by a QAnon promoter elevated the video. Ambiguity also played a key role, as an LA Times interview with filmmaker Mikki Willis suggests.

Faithful prays for their religious leader Naason Joaquin Garcia, arrested in California, US, facing charges for 26 suspected felonies including human trafficking, rape of minor and child pornography, at the international headquarters of the Church ‘La Luz Del Mundo’ (Light of the World) in Guadalajara, Jalisco State, Mexico on June 9, 2019.Photo by Ulises Ruiz / AFP via Getty Images

After Willis admits “Plandemic” is intentionally “conspirational and shocking,” the reporter presses him to validate Judy Mikovits’s claims. Willis admits leaving in unsubstantiated claims “that could be true, but science hasn’t proven it yet”—an effectively meaningless statement. Anything could be true. Science is the process of discovering whether or not a claim holds up.

Truth was never the point. The reporter goes on, “as [Willis] sees it, he is simply offering a necessary alternative to what he calls ‘the mainstream narrative.'” Willis himself admitted to another reporter that “Plandemic” is propaganda.

Which narrative? Irrelevant. Suspicion has been expressed. Ambiguity is power.

Matthew Remski specializes in cult dynamics and trauma, predominantly in yoga and Buddhist communities. In his excellent summation of Willis’s response, which the filmmaker recorded after “Plandemic” went viral, Remski points out that Willis failed to address his video’s content. Instead, he used time-tested cult techniques to sway the observer to his “side.”

“In my research on charismatic leadership, many interview subjects report the paradoxical phenomena of the speaker speaking to countless people, while seeming to forge a private connection. Some of this is amplified by the webcam medium, but it’s also played up with direct 2nd-person address. As the sermon finds its ultimate/totalistic theme, the diction shifts to first-person plural. The viewer is invited to merge with the speaker. The sermon is about something ultimately important, communicated in close intimacy.”

This is Willis’s first public message after his video (marketed during the interview as scientific fact) was viewed over eight million times. Mikovits’s claims are not presented as speculation. She repeatedly contradicts herself. She probably makes false statements. Doesn’t matter. This technique has precedent, having been perfected by our current president over the course of decades: State an absurd or inflammatory idea as possible, let it escalate in the public imagination, then step back and claim no responsibility. Birtherism was a litmus test.

While Mikovits has been doubling and tripling down on her false claims, Willis calls himself an investigative journalist. Releasing an interview with an unvetted subject without researching her claims is the opposite of journalism. “Plandemic” is propaganda masquerading as investigation. The film is perfect fodder for the conspiracist ethos.

Why conspiratorial thinking is peaking in America | Sarah Rose Cavanagh | Big Thinkwww.youtube.com

Conspiracy theories are low-beta transmissions—simplistic messages designed to satisfy an answer in search of a question. Tragically, they distract us from real conspiracies, which Lewandowsky says are “usually uncovered by journalists, whistleblowers, document dumps from a corporation or government, or it’s discovered by a government agency.” Hard work when the public’s default response is to yell out “fake news” when their beliefs are challenged. A transmission right from the cult leader’s mouth.

“Plandemic” exploits a particular style of paranoid thinking rampant in divergent cultures: Far-right conspiracy theorists like QAnon, anti-vaxxers, and leftist “wellness” advocates. A new cult is forming right before our eyes. While an agenda is not yet clear, identifying leaders is the first step in creating one.

Tara Haelle, senior contributor to Forbes, does an exceptional job explaining how to push back against conspiracy theories like “Plandemic.” A comprehensive list of articles debunking the many “facts” presented during the interview is included at the end of the linked post.

Every article I’ve read about combating conspiracy theories advises to focus your attention on the uninitiated, which is most likely true. Explaining basic vaccine science to a QAnon member likely won’t get you far. It’s not impossible, however. For a deep dive into saving cult members, check out Steve Hassan’s 1988 book, “Combating Cult Mind Control” (it was updated in 2015).

Having been indoctrinated himself, Hassan says that presentation of contradictory evidence often “made me feel more committed to the group.” That doesn’t make the attempt hopeless, however. Understanding the indoctrination process helps you combat it. Hassan continues,

“Deception is the biggest tool of information control, because it robs people of the ability to make informed decisions. Outright lying, withholding information and distorting information all become essential strategies, especially when recruiting new members.”

For the first time in a century, Americans are grappling with a public health crisis involving every citizen. An information war is being waged. This is not the time to be a “keyboard warrior.” We have to take a critical but honest look at experts who have devoted their lives to public health. And we need to listen.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook. His next book is “Hero’s Dose: The Case For Psychedelics in Ritual and Therapy.”