Mechanical Turk: An elaborate 18th-century hoax that played chess like an AI robot

- The Mechanical Turk, a wooden box containing an elaborate mechanism inside and a mannequin on top, played chess against — and defeated — Benjamin Franklin, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Charles Babbage.

- After 60 years of fooling the world, Edgar Allan Poe revealed why he believed the Turk was a hoax.

- Alas, the Turk was not the first AI robot; there was a human on the inside.

This is the 21st century, and we are still waiting for true AI. But back in the 18th century, there was a chess machine that behaved somewhat like today’s AI. Known as the Mechanical Turk, it ended up being a carefully engineered hoax that fooled people into believing that an automated mannequin could defeat humans at chess.

The Mechanical Turk toured across Europe, playing chess against personalities like Charles Babbage and Napoleon Bonaparte. The machine was developed by Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770 to fulfill a promise that he made to Queen and Empress Maria Theresa.

A year before the invention of the Turk, a magician arrived in the court of the empress and performed an illusionary act that mesmerized everyone, including Kempelen. Astounded by the magician’s performance, Kempelen told the Empress that he would soon invent something that would surpass the magician’s illusion. One year later, Kempelen was standing in the court alongside the Mechanical Turk.

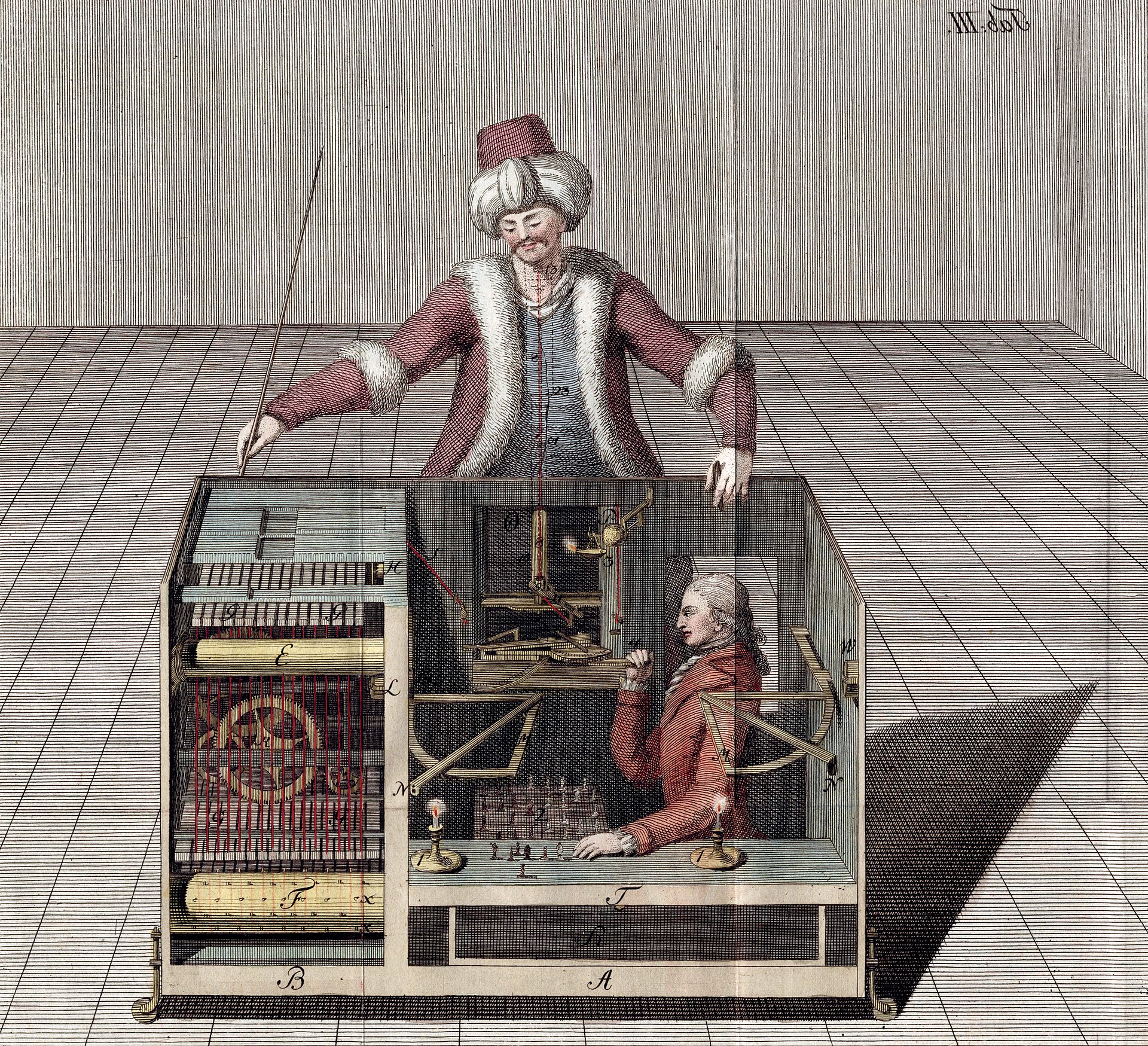

The Mechanical Turk looked like a wooden box with a life-sized mannequin placed on the top. The mustached mannequin had the attire and looks of an Ottoman magician, complete with a turban, robe, and classic smoking pipe in one hand.

The wooden box had dimensions of 3.5 x 2 x 2.5 feet. Before every chess game, Kempelen would show the internal component of the machine to the audience. It contained three doors at the front and a sliding drawer at the bottom. These different sections of the machine contained chess pieces, a chess board, and numerous clockwork components.

The Turk goes on tour

During the first demonstration of the Mechanical Turk before Empress Theresa, Kempelen invited many members of the court to play chess against the machine, and surprisingly all of them were defeated. People were amazed to see an intelligent automated machine for the first time, and news of it quickly spread across the continent.

In his book, The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth Century Chess-Playing Machine, author Tom Standage said, “Unlike the new machines of the industrial revolution… [the Turk] raised the possibility that machines might eventually be capable of replacing mental activity too.”

Soon, Kempelen started receiving invitations and requests from many other members of the Habsburg royal family to demonstrate the Turk’s game. Joseph II, son of Empress Theresa, then sent him and the Turk on a European tour, in which the machine played against many intelligent and famous personalities during its journey.

It defeated prominent American scientist and politician Benjamin Franklin and was investigated by researchers from the French Academy of Sciences to reveal the secret behind its automated functions. (They couldn’t find it.) However, the Turk also experienced its first defeat at the hands of Europe’s number one chess player at that time, François-André Danican Philidor.

Although Kempelen died due to abdominal blockage in 1804, the machine continued touring Europe with its new owner, Johann Mälzel (a German engineer).

The Turk was so good at playing chess that, not only did it defeat most of the humans it played, it could also point out if someone cheated during a game. If the mannequin noticed a human player cheating, it demonstrated its objection by either reversing its opponent’s move or heavily thumping on the chess board and ending the game.

The latter happened once when the Turk played against Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809. Napoleon played two games against the Turk. In the first, he made three illegal moves. The Turk objected and ended the game by wiping all the chess pieces off the board using its arm. In the second game, Napoleon lost against the machine.

The Mechanical Turk also played two chess games with Charles Babbage, the famous inventor who developed the first computer. It emerged victorious in both games.

Edgar Allan Poe reveals the hoax

Of course, the Turk was not powered by artificial intelligence, and many people including Charles Babbage had raised doubts about the automated activity of the chess player. They believed that it wasn’t the mannequin, but a secret human operator, who played the games. However, the Turk was designed so intelligently that none of them could prove their theories with solid evidence.

The Turk managed to amaze and fool people for 60 years until American writer and critic Edgar Allan Poe wrote an essay in 1836. Titled “Maelzel’s Chess Player,” Poe suggested that there should be some key differences between a true machine and a fake one. For instance, he proposed that a true machine should win all matches and display a pattern or make moves in a fixed time interval — but the mannequin didn’t show any such characteristics.

Moreover, Poe suggested that the complex clockwork inside the machine was used as a cover for a secret player who controlled the mannequin from the inside. Later, when the machine was inspected further, a secret space was found hidden behind the clockwork setup in the left door and the bottom drawer of the wooden cabinet. Hidden magnets linked to the chessboard on the top were also discovered inside the secret space of the cabinet. These magnets allowed the human chess player to keep an eye on the position of the chess pieces during the game.

The telltale Turk

People started losing interest in the Mechanical Turk after Poe’s findings were published. Mälzel also noticed that he was getting fewer invitations for demonstrating the chess player, but before he could do something about it, he died. The Turk eventually ended up in a museum in Philadelphia where it got burned during a fire on July 5, 1854. Fortunately, some components of the original Turk were recovered.