Out of Africa: Not just once, but many times

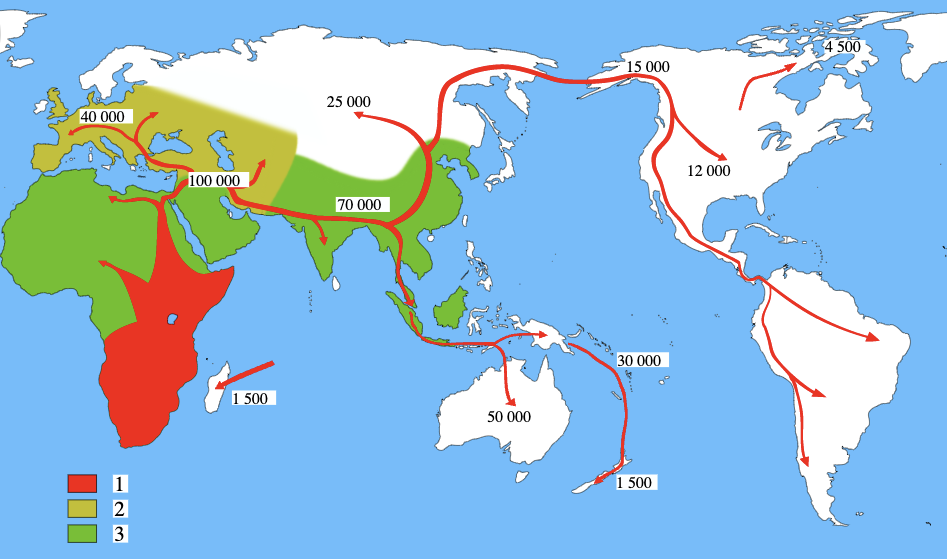

- It is widely agreed that humans first evolved in Africa and then migrated into other parts of the world.

- However, there remain many open questions within this “Out of Africa” theory of early hominin migration.

- A recent analysis of an ancient hominin fossil shows that there were at least two “dispersal events” out of Africa by two different hominin species some 300,000 years apart.

In the story of how early hominins evolved and spread across the planet, few places are as important as the Levantine corridor, the land bridge that connects Africa with Eurasia. It was through this passage that many ancient hominins left Africa. The remains of those who crossed, and the artifacts they left behind, offer a wealth of evidence into when and how these migrations — or “dispersal events” — occurred, the first of which took place nearly two million years ago.

These dispersal events form the basis of the “Out of Africa” theory of early hominin migration. Although the theory is widely accepted, there are still many open questions regarding exactly when early hominins migrated into Eurasia, whether that migration occurred in waves or a single event, and what ecological factors might have pulled many of them to the north.

A recent analysis of a 1.5-million-year-old vertebra discovered in modern-day Israel sheds light on ancient dispersal events. The study provides solid evidence that, in the Early Pleistocene period, there were at least two distinct waves of hominin migration, each of which involved distinct hominin species. The fossil is also the second-oldest hominin bone found outside of Africa. The results were published in Scientific Reports.

A child meets a bad fate in ‘Ubeidiya

In the Levant region, the only site where archaeologists have unearthed hominin remains that date 1.1 to 1.9 million years old is ‘Ubeidiya, located in Israel at the western escarpment of the Jordan Valley. Since the late 1950s, researchers have been searching the land and discovering ancient fossils and artifacts, though technological limitations meant they didn’t always have a clear understanding of what they had unearthed.

One example is the fossil analyzed in the recent study: a complete lower lumbar vertebra with hominin characteristics. The fossil was discovered in 1966, but for decades, nobody had been quite sure what it was; it had long been stored alongside ancient monkey bones. It was clear that the fossil was a vertebra, but of which species? After all, the remains of numerous animals — monkeys, hyenas, elephants — had been discovered at the ‘Ubeidiya site, so the answer wasn’t immediately clear.

The recent study used modern imaging techniques to compare the vertebra with those of other ancient creatures. The results show that the fossil almost certainly belonged to a large-bodied bipedal hominin. How did the researchers know? Because us bipeds walk upright, our lower back supports a relatively large share of our body weight, so our vertebrae are shaped differently than, say, a monkey’s. The shape of the vertebra is consistent with hominins, specifically a young and rather tall hominin between the ages of 6 and 12 years. Based on the age of other artifacts found at the same site, the child likely lived 1.5 million years ago.

Updating “Out of Africa”

The child who died at ‘Ubeidiya was indeed ancient. But they and their fellow hominins who walked the Levantine corridor some 1.5 million years ago were far preceded by another hominin species: an ancient group discovered in Dmanisi, Georgia, who date back 1.8 million years. The two groups differed not only in location, time, and technology (the Dmanisi created less complex tools than the ‘Ubeidiya), but also in genetics: The ‘Ubeidiya had bigger bodies than the Dmanisi, and the areas to which they migrated suggest they had evolved different ecological and behavioral adaptations.

It’s still not exactly clear where the ‘Ubeidiya species lies on the evolutionary tree. However, researchers noted that the size of the fossil suggests it would have been too large of a creature to be classified as a Homo habilis, one of the earliest of the Homo species. The fossil more closely resembles Homo erectus, which first emerged approximately two million years ago and is considered by many scientists to be an ancient ancestor of modern humans.

What the recent study does confidently show is that ancient hominin migration was not a one-off event. Across nearly unfathomable timescales, there were multiple times when distinct groups of early hominins walked upright out of Africa toward new land, starting with Eurasia and ending with the Americas.