Venus, Not Earth, May Have Been Our Solar System’s Best Chance At Life

If we started all over again, could our Solar System’s second planet have been the inhabited one?

“It was the Venus I had prayed to, it was my prayer, though I had no such words. They filled my eyes with tears and my heart with inexpressible joy.”

–Ursula Le Guin

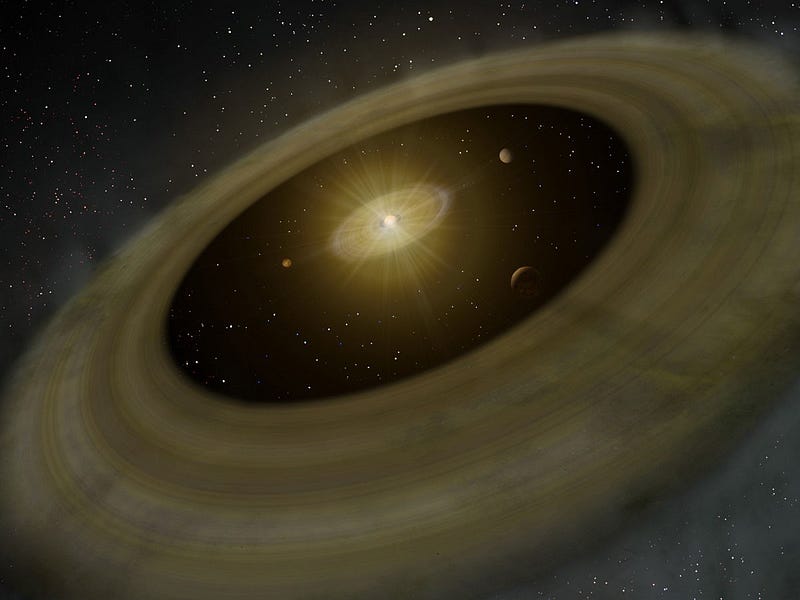

If we were to wind the clock back some 4.5 billion years ago, to the early days of our Solar System, we would have seen a young, G-class star with four rocky worlds interior to our asteroid belt. Like many of the star systems the Kepler spacecraft has discovered, this type of configuration is relatively common; there are billions upon billions of chances in our galaxy alone that began just like ours did. But the young worlds in our newborn Solar System were very different from how they are today, and so was the Sun, for that matter.

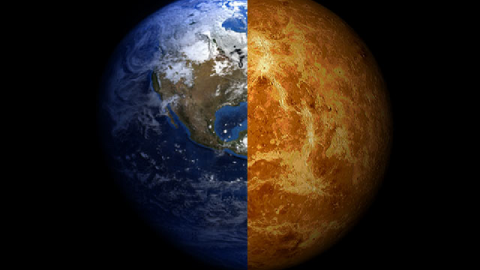

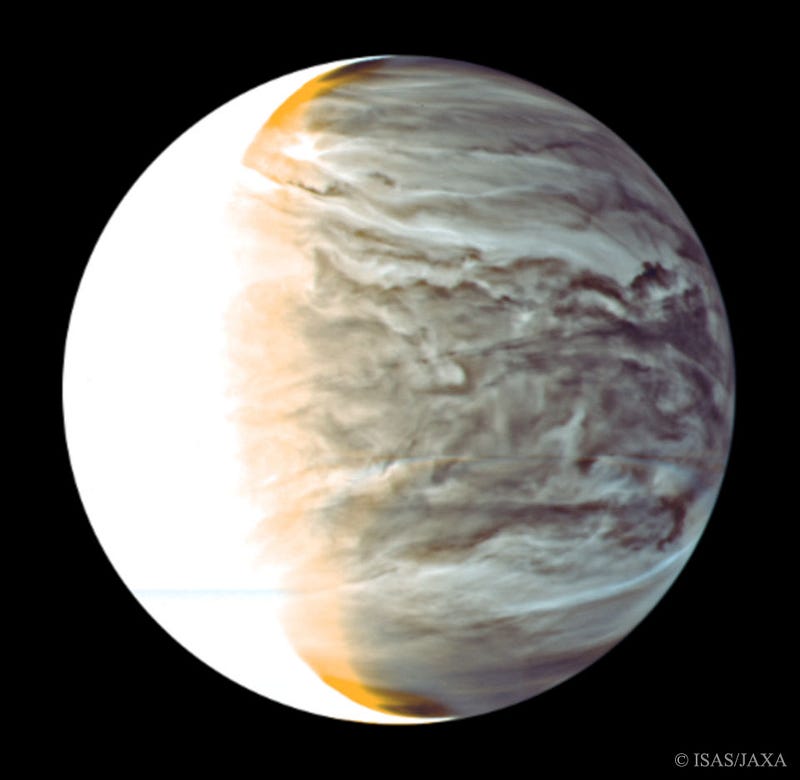

Venus’ atmosphere was very thin at the beginning, comparable to the thickness of Earth’s atmosphere today. Earth, on the other hand, was very different, with lots of methane, ammonia, water vapor, hydrogen and virtually no oxygen at all. And the Sun was so faint compared to what it is now: less than 80% as luminous as it is today. With all that in mind, perhaps — if we rewound the Solar System to the very beginning and started it again — the ingredients for life would come together on Venus far more easily than on Earth? And perhaps early Venus was teeming with life, while things on Earth were barely getting started?

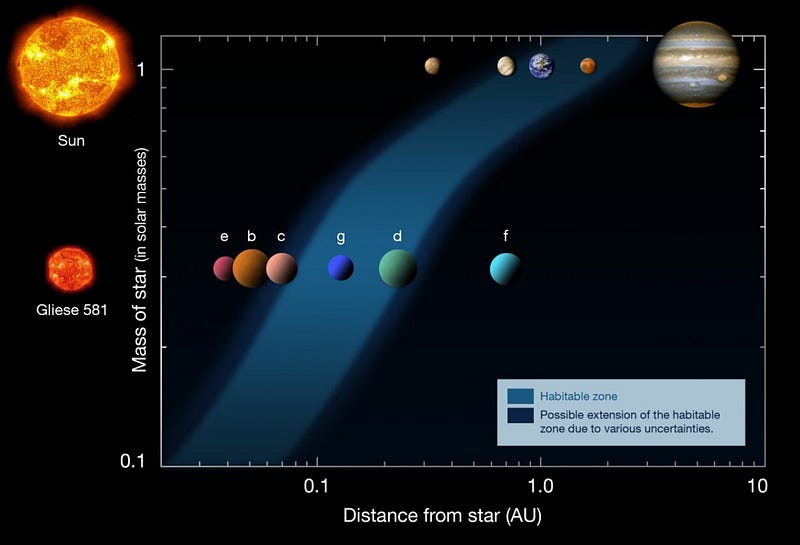

Things didn’t need to turn out the way they did, even given the initial conditions the Solar System began with. And perhaps that makes it worth reconsidering an assumption we make: perhaps the habitable zone shouldn’t be defined by the location in the Solar System where an Earth-sized planet with an Earth-like atmosphere would have the right pressure-and-temperature combinations for liquid water on its surface? Perhaps, instead, we should consider the possibility that, just as a nudge in the wrong direction could have rendered early Earth either an inferno or a frozen wasteland, perhaps a nudge in the right direction would have led to life thriving on Venus or Mars . In other words, perhaps what we think of as the “habitable zone” of a star is actually much broader — and more variable — than we’ve thought up to this point.

This is exactly what Adrian Lenardic and collaborators consider in their latest article, published in the journal Astrobiology. What they explore is the possibility that if you began the Solar System anew with only very slight, perhaps imperceptible changes in the initial conditions, perhaps Venus, Earth or even Mars (or all three) might emerge with life thriving on them. The similar size and composition of Venus and Earth, their likely similar early histories coupled with their vastly different outcomes was once thought of as an inevitability. But as more planets are discovered and characterized, we may find out that the truth is vastly different from those expectations.

“[I]f you could run the experiment again, would it turn out like this solar system or not? For a long time, it was a purely philosophical question. Now that we’re observing solar systems and other planets around other stars, we can ask that as a scientific question. If we find a[n exo]planet sitting where Venus is that actually has signs of life, we’ll know that what we see in our solar system is not universal,” Lenardic said. As the next generations of exoplanet missions go from the planning stages to construction to operation, signs of life — to go from potentially habitable to inhabited — could become a reality. Plans to directly image rocky alien exoplanets or to view the starlight filtering through the atmosphere could reveal worlds with oceans, continents, seasonal changes, or, perhaps most tellingly, oxygen-rich atmospheres.

Yet even an absence of oxygen might not be a dealbreaker. After all, Earth had life for billions of years before our atmosphere became oxygen-rich, and it’s even possible that plate tectonics may not have become active on our world 2-to-3 billion years ago. “There are things that are on the horizon that, when I was a student, it was crazy to even think about,” Lenardic continued. “Our paper is in many ways about imagining, within the laws of physics, chemistry and biology, how things could be over a range of planets, not just the ones we currently have access to. Given that we will have access to more observations, it seems to me we should not limit our imagination as it leads to alternate hypothesis.”

Just as a planet’s location, pressure, temperature, composition, magnetic and geologic properties and more may influence whether it has life on its surface or not, that life may feed back onto the planet itself, perhaps altering its course in ways we do not yet understand. As we move from the realm of speculation into the era of data-rich information about alien worlds, we may find that life is far more common — and inhabited worlds are far more diverse — than we’ve ever considered before.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!