Yes, you can see sounds — it’s called cymatics

Photo by Mathilde Langevin on Unsplash

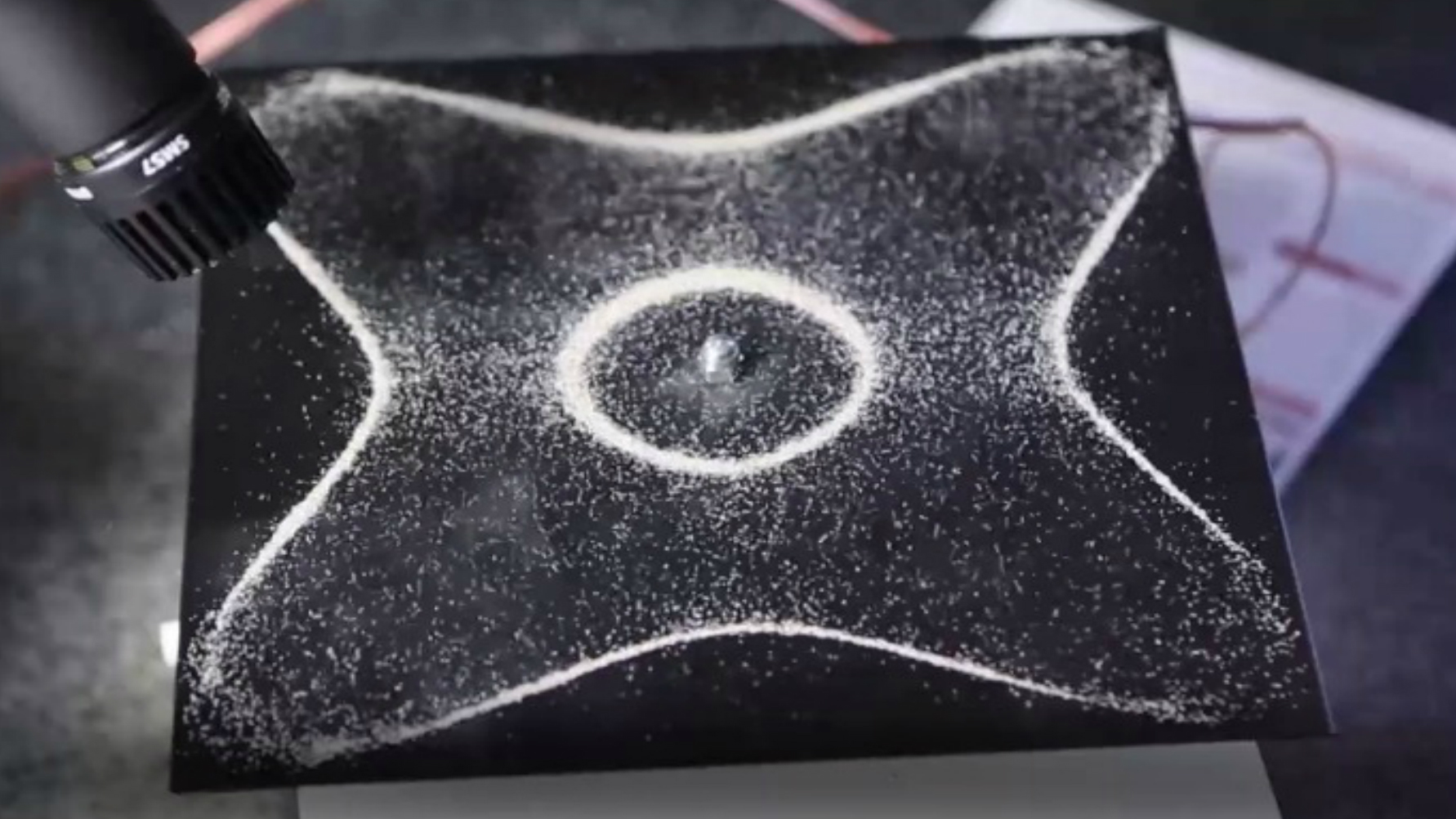

Sound can be visible. What’s more, sound can draw exquisite, regular patterns on a physical surface.

If you ever tried playing on a wine glass or tracing squeaky circles along the rim of a thin champagne flute at a boring (albeit boozy) party, you have officially passed one of the most impressive physics courses there is. What is so incredible about playing with glass (except the spectacular sound effects, of course)?

If the alcohol percentage in the glass allows it, let us look at what happens inside the glass. A slight, constant rubbing of the rim can cause a pretty big storm. Droplets detach from the smooth surface of the drink and rhythmically bob up and down, while the troubled waves bounce off the see-through sides. The whole show creates dynamic forms and shapes that depend on the frequency of the sound, which is sensitive to the smallest caress of the fingertip. Stories about rubbing genie lamps only gained academic interest in the 1970s. The field of research that studies the shape of sound waves became known as cymatics. However, sound waves and the effect they have on matter had become an object of fascination long before that.

When glasses were clinking at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 to celebrate the signing of the Constitution, 6505 kilometres away in the town of Lipsk amateurs of various scientific curiosities were avidly reading Entdeckungen über die Theorie des Klanges (Discoveries in the Theory of Sound), written by Ernst Chladni, a lawyer, geologist, inventor, designer and acoustician. This exemplary son of a law professor graduated in the same field of study as his father, on Dad’s orders. Nevertheless, the heir dreamed of a different future. He waited for his father to pass on, then abandoned paragraphs in favour of his fantasies – sound experiments – without remorse. Admittedly, it was too late to go for the career of a musician, but the young man’s proclivity for performing slowly became more and more apparent. Ernst Florens Friedrich Chladni was sucked into a whirlwind of soundwaves for good. He toured all over Europe, amazing his audiences (and Napoleon himself) with various sound shows and instruments of his own making. His signature moves must have inspired the jealousy of local illusionists. Chladni proved that sound can be seen, and developed his own technique of visualizing vibrations on a metal plate. He produced images that were never dreamed of, even in philosophy.

One of his tricks was to steadily slide his bow along the edge of a flexible metal plate. The brass plates were covered with fine sand and thus reacted to the slightest vibrations. The grains convoluted into unbelievably regular patterns that depended on the frequency of the sound and the texture of the surface that was made to resonate. The boundary conditions also turned out to be relevant: the way the plates were pinned down, as well as the exact points of contact where the vibrations were generated. Since it would be better not to take these subtleties any further, let’s limit the use of professional nomenclature to knowledge for the so-called whizzes.

However, a few words may come in handy about the forefathers of experimental acoustics, whose works Chladni had laboriously studied. It is enough to mention naturalist Robert Hooke’s efforts to reproduce sound visually (he and Chladni also shared a love for stargazing). What’s more, it is possible that the German physicist sent a copy of The Theory of Sound to the Philadelphia Convention, because the musical discoveries of Benjamin Franklin, one of America’s Founding Fathers, were an inspiration for Chladni.

200 years later, cymatics has become a catchy topic not only for acousticians, but for visual arts students and graduates, too. Apart from the fact that Chladni’s patterns portray sound and are an anecdote worth mentioning in various toasts, they can also be put to good use by instrument makers. In this context, marching to the beat of your own drum takes on an entirely new meaning.

Translated from the Polish by Joanna Piechura

Reprinted with permission of Przekrój. Read the original article.