Stephen Petranek, author of How We’ll Live on Mars, details several of the methods a future team of colonists could employ in order to amass a drinking water supply on Mars. There’s plenty of water on the planet; the trick is extracting it from the soil and atmosphere. It’s a relief that producing water won’t be a major nuisance for the eventual Mars astronauts — that whole “unlivable barren wasteland” is a whole other story.

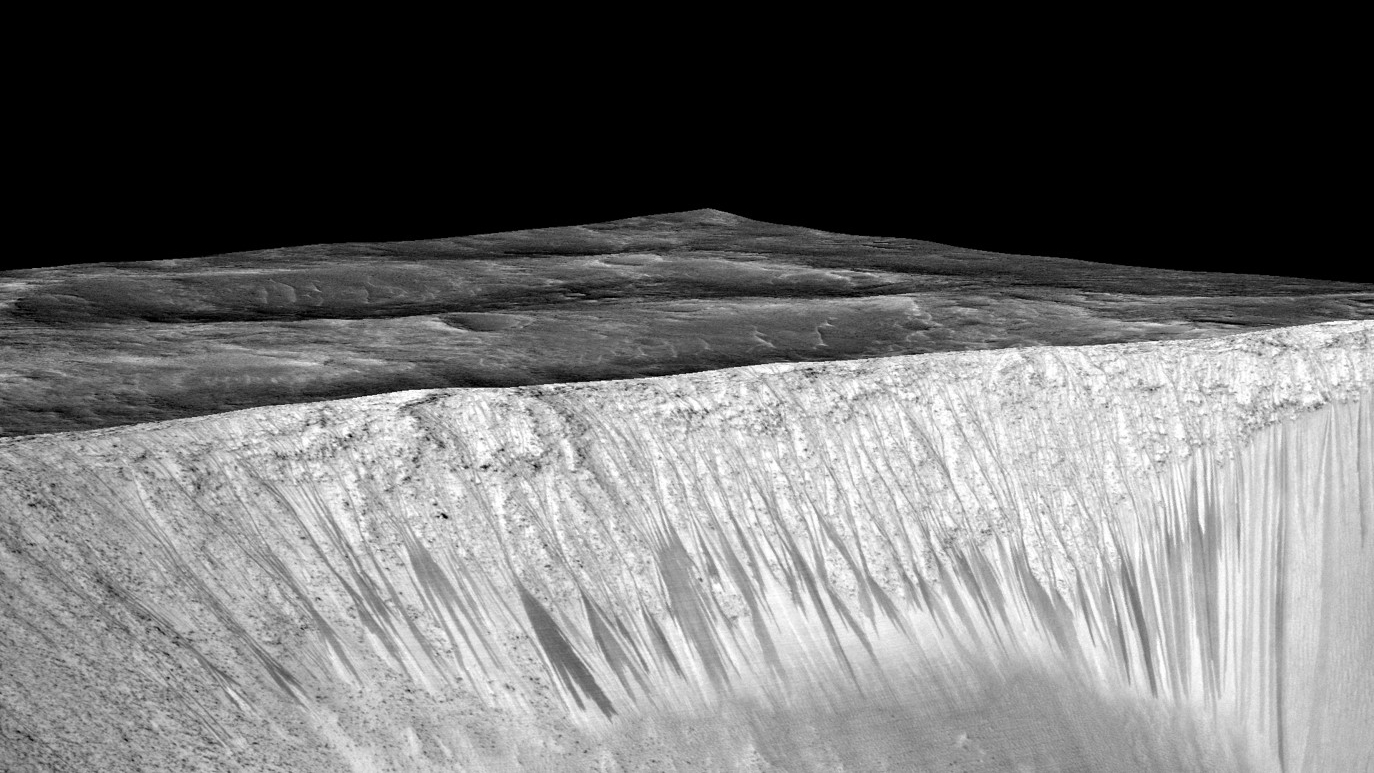

Stephen Petranek: There is a lot of water on Mars and there once was a lot of surface, flowing water. You don’t see it because most of it is mixed with the soil, which we call regolith on Mars. So the Martian soil can be anywhere from as little as 1 percent in some very dry, deserty like areas to as much as 60 percent water. So one strategy for getting water when you’re on Mars is to break up the regolith, which would take something like a jackhammer because it’s very cold; it’s very frozen. If you can imagine making a frozen brick or a chunk of ice that’s mostly soil and maybe half water and half soil that’s what you would be dealing with. So you need to break this up, put it in an oven. As it heats up, it turns to steam. You run it through a distillation tube and you have pure drinking water that comes out the other end. There is a much easier way to get water on Mars. In this country, we have developed industrial dehumidifiers. And they’re very simple machines that simply blow the air in a room or a building across a mineral called zeolite. Zeolite is very common on Earth; it’s very common on Mars. And zeolite is kind of like a sponge. It absorbs water like crazy. Takes the humidity right out of the air. Then you squeeze it and out comes the water. And scientists working for NASA at the University of Washington as long ago as in the late 1990s developed a machine called WAVAR that very efficiently sucks water out of the Martian atmosphere. So water is not nearly as significant a problem than it appears to be. We also know from orbiters around Mars and right now there are five satellites orbiting Mars. We know from photographs that these orbiters have taken and geological studies that they’ve done that there is frozen ice on the surface of Mars. Now there’s tons of it at the poles. Some of it is overladen with frozen — or mixed with frozen carbon dioxide. But in many craters on Mars, there apparently are sheets of frozen water. So if early astronauts or early voyagers to Mars were to land near one of those sheets of ice in a crater they would have all the water they need.