Changing a brain to save a life: how far should rehabilitation go?

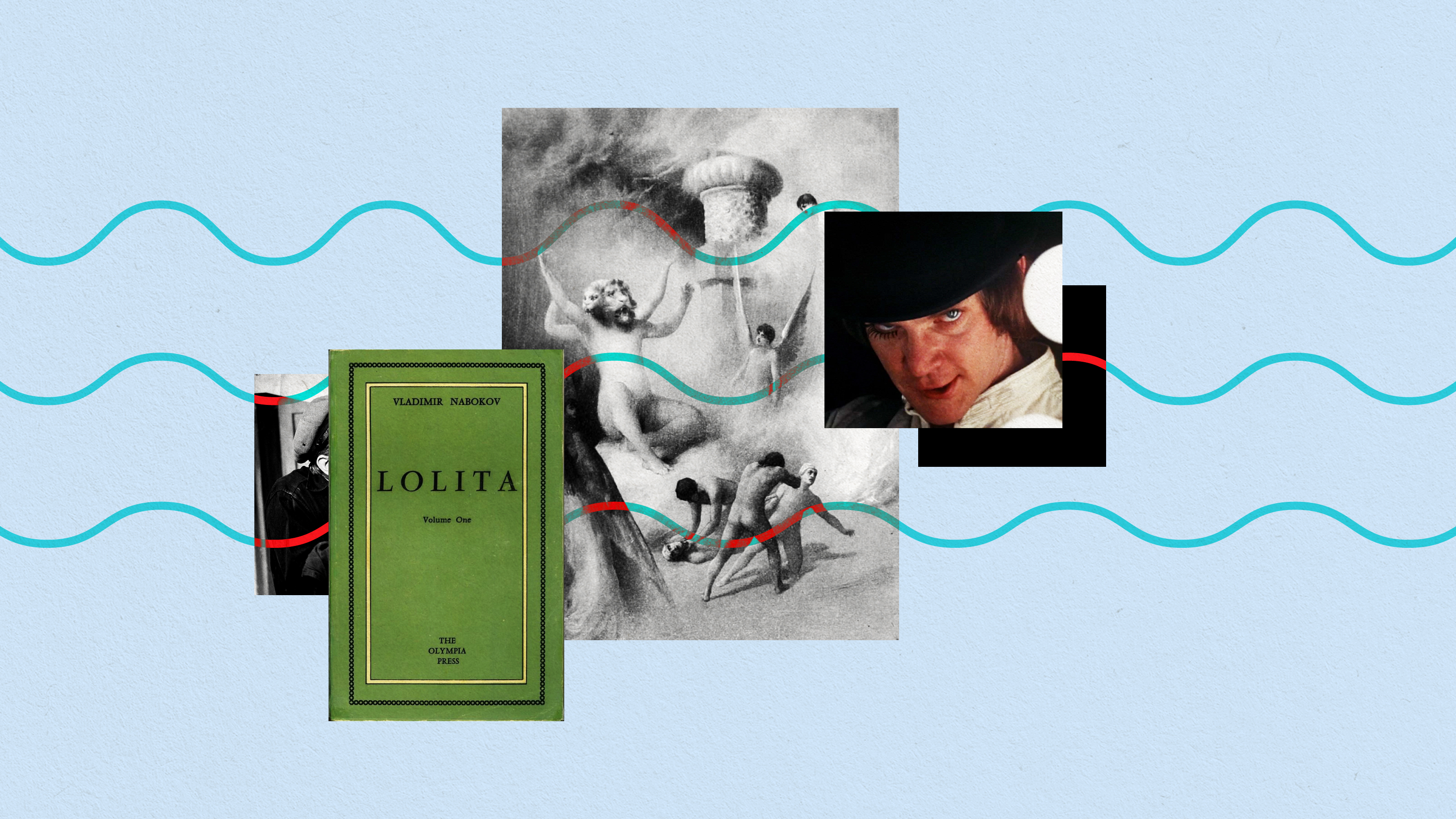

- The book and movie, A Clockwork Orange, powerfully asks us to consider the murky lines between rehabilitation, brainwashing, and dehumanization.

- There are a variety of ways, from hormonal treatment to surgical lobotomies, to force a person to be more law abiding, calm, or moral.

- Is a world with less free will but also with less suffering one in which we would want to live?

Alex is a criminal. A violent and sadistic criminal. So, we decide to do something about it. We’re going to “rehabilitate” him.

Using a new and exciting “Ludovico” technique, we’ll change his brain chemistry to make him an upstanding, moral citizen. Alex will be forced to watch violent movies as his body is pumped with nausea-inducing drugs. After a while, he’ll come to associate violence with this horrible sickness. And, after a course of Ludovico, Alex can happily return to society, never again doing an immoral or illegal act. He’ll no longer be a danger to himself or anyone else.

This is the story of A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess, and it raises important questions about the nature of moral decisions, free will, and the limits of rehabilitation.

Today’s Clockwork Orange

This might seem like unbelievable science fiction, but it might be truer — and nearer — than we think. In 2010, Dr. Molly Crockett did a series of experiments on moral decision-making and serotonin levels. Her results showed that people with more serotonin were less aggressive or confrontational and much more easy-going and forgiving. When we’re full of serotonin, we let insults pass, are more empathetic, and are less willing to do harm.

As Fydor Dostoyevsky wrote in The Brothers Karamazov, if the “entrance fee” for having free will is the horrendous suffering we see all around us, then “I hasten to return my ticket.”

The idea that biology affects moral decisions is obvious. Most of us are more likely to be short-tempered and spiteful if we’re tired or hungry, for instance. Conversely, we have the patience of a saint if we just have received some good news, had half a bottle of wine, or had sex.

If our decision-making can be manipulated or determined by our biology, should we not try various interventions to prevent the criminally inclined from harming others?

Drastic interventions

What is the point of prison? This is itself no easy question, and it’s one with a rich philosophical debate. Surely one of the biggest reasons is to protect society by preventing criminals from reoffending. This might be achievable by manipulating a felon’s serotonin levels, but why not go even further?

Today, we know enough about the brain to have identified a very particular part of the prefrontal cortex responsible for aggressive behavior. We know that certain abnormalities in the amygdala can result in anti-social behavior and rule breaking. If the purpose of the penal system is to rehabilitate, then why not “edit” these parts of the brain in some way? This could be done in a variety of ways.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a surprisingly common practice in much of the developed world. Its supporters say that it can help relieve major mental health issues such as depression or bipolar disorder as well as alleviate certain types of seizures. Historically, and controversially, it has been used to “treat” homosexuality and was used to threaten those misbehaving in hospitals in the 1950s (as notoriously depicted in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). Of course, these early and crude efforts at ECT were damaging, immoral, and often left patients barely able to function as humans. Today, neuroscience and ECT are much more sophisticated. If we could easily “treat” those with aggressive or anti-social behavior, then why not?

Ideally, we might use techniques such as ECT or hormonal supplementation, but failing that, why not go even further? Why not perform a lobotomy? If the purpose of the penal system is to change the felon for the better, we should surely use all the tools at our disposal. With one fairly straightforward surgery to the prefrontal cortex, we could turn a violent, murderous criminal into a docile and law-abiding citizen. Should we do it?

Is free will worth it?

As Burgess, who penned A Clockwork Orange, wrote, “Is a man who chooses to be bad perhaps in some way better than a man who has the good imposed upon him?”

Intuitively, many say yes. Moral decisions must, in some way, be our own. Even if we know that our brains determine our actions, it’s still me who controls my brain, no one else. Forcing someone to be good, by molding or changing their brain, is not creating a moral citizen. It’s creating a law-abiding automaton. And robots are not humans.

And yet, it begs the question: is “free choice” worth all the evil in the world?

If my being brainwashed or “rehabilitated” means children won’t die malnourished or the Holocaust would never happen, then so be it. If lobotomizing or neuro-editing a serial killer will prevent them from killing again, is that not a sacrifice worth making? There’s no obvious reason why we should value free will above morality or the right to life. A world without murder and evil — even if it meant a world without free choices for some — might not be such a bad place.

As Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote in The Brothers Karamazov, if the “entrance fee” for having free will is the horrendous suffering we see all around us, then “I hasten to return my ticket.” Free will’s not worth it.

Do you think the Ludovico technique from A Clockwork Orange is a great idea? Should we turn people into moral citizens and shape their brains to choose only what is good? Or is free choice more important than all the evil in the world?

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.