To my unknown family in Ukraine

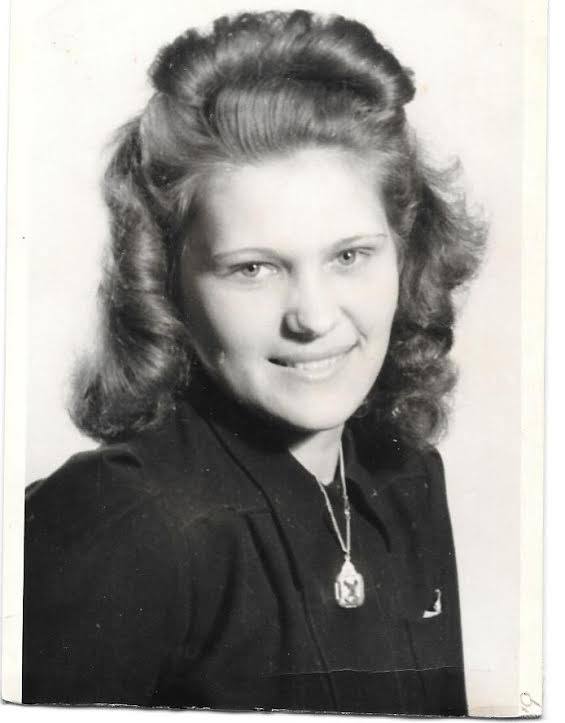

- My grandmother was born in Druzhkivka, a town located in the province of Donetsk, much of which has been occupied by pro-Russian separatists since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014.

- Russia has long sought to erase the mere idea of Ukraine, falsely claiming that there is no such thing as Ukrainian identity.

- My grandmother eventually made it to America, but many of my (unknown) relatives still live in Ukraine.

My grandmother was born in Druzhkivka, a town located in the province of Donetsk in eastern Ukraine. The province is part of a greater region known as Donbas, much of which has been occupied by pro-Russian separatists since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014.

Ukraine has a long, tragic history of immense suffering under Russian rule. The most egregious example was the plundering of Ukraine by the Bolsheviks, later perfected under Joseph Stalin. Now known as the Holodomor, Stalin ordered the mass starvation of millions of Ukrainians. Ukraine was known as the “breadbasket of Europe,” and — as punishment for rebellion (both real and perceived) — Stalin declared that all food should be confiscated from the country.

A gut-wrenching description of what this was like, based on a book called Red Famine by Anne Applebaum, was published in The New Republic. It reads:

“People crawled into wheat fields to eat ears of wheat before dropping dead. They died from hunger in the act of eating. Children collapsed and died during lessons. A mother took the bread from her offspring to feed her husband (she could, she said, always have more kids, but she could only ever have one husband). A couple put their children in a deep hole and left them there, in order not to watch them die. A father strangled his own children rather than watch them perish from hunger. Communities that had once been kind and welcoming became mistrustful and violent; lynch mobs tortured people. And in the end, most horrifically of all, people began to eat each other.”

To my knowledge, none of my more immediate family succumbed to this fate. But I remember my grandmother telling us a story about how she would check each morning to see if any of her family members had died in their sleep.

Erasing Ukraine: a Russian obsession

The assault on Ukraine wasn’t just physical; it was also psychological and intellectual. As the aforementioned article describes, Russia has long sought to erase the mere idea of Ukraine. This belief, that Ukraine is not a real country, permeates the mindset of Russia’s leaders. And that explains Vladimir Putin’s dubious essay in 2021, titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” The essay was widely condemned as revisionist history. Of the many things Putin gets wrong is the notion that Ukrainians are not a separate people from the Russians. But in an essay for The Atlantic, Anne Applebaum notes that Ukrainian identity goes back to at least the 16th or 17th century.

Before we analyze Putin’s actions today, we first need to rewind the timeline back to 2014. That was the year that Russia seized the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine. Why did it do that? Despite its massive size, Russia is essentially landlocked. The northern part of the country faces the Arctic Ocean, which is iced over much of the year. Although the eastern part of the country borders the Pacific Ocean, it is sparsely populated. Russia’s population center is in the west, but that frontier is bordered by (what Russia perceives to be) a hostile European Union and NATO. From that perspective, the Baltic and North Seas are essentially enemy territory — impassible in the event of a war.

That leaves the southern border, which isn’t next to an ocean. That means the only way that Russia can safely get there is through the Black Sea via the Bosporus Strait (which literally divides Istanbul into its western (European) and eastern (Asian) halves). But much of the land that borders the Black Sea, like the Crimean Peninsula, is in Ukraine. Even worse (from Russia’s viewpoint), Sevastopol — the major Crimean port city — hosts a Russian naval base. So, when the Ukrainians revolted in 2013-14 and the pro-Russian president was booted in favor of a pro-Western one, Putin interpreted this as an unacceptable risk to Russian national security. Thus, he invaded to protect his Black Sea fleet in Sevastopol.

What does Putin want?

And that brings us to today. While Putin’s initial invasion in 2014 was odious and reprehensible, it was also at least geopolitically explainable. It served a purpose: Keep the warm water port secure. But what is the point of the invasion now?

Nobody really knows. Is it to restore the glory days of the Soviet Union? Is it to install a puppet regime in a vassal state à la Belarus? Is it to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO? Is it to distract from his own growing unpopularity at home? Is it because Putin thought not invading would be a sign of weakness? Is it just one gigantic ego trip? All of the above?

The speech Putin gave right before the invasion was downright chilling. In it, he claimed that Ukraine needed to be “de-Nazified” — perhaps a throwback to the Soviet claim that any mention of the Holodomor was Nazi propaganda. Whatever he meant, it was deeply insulting. The president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish. His grandfather’s siblings were murdered in the Holocaust.

To my unknown family in Ukraine

As it turned out, my grandmother’s bad luck did not end in Ukraine. Following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, she was kidnapped and taken to Germany as slave labor. (The same happened to my Russian grandfather, and the two of them met in a war camp there.) Following the war, they were among the millions of refugees seeking a new home — something that surely will happen again as Russia invades Ukraine. One estimate suggests there will be five million Ukrainian refugees.

Eventually, my grandparents settled in the U.S., but they had unfinished business in the old country. My grandmother had not seen or spoken to her family in years. She was particularly close to her mother, yet she had no idea whether her mother was even still alive. Then, after 32 years without contact, they finally reconnected in 1974. The story made international headlines.

To my unknown family in Ukraine: Though I don’t know any of you, I know you’re there — and my thoughts and prayers are with you all. And I especially pray that the U.S., EU, and NATO will wake up to the new reality that confronts them this day.