The plastic paradox: How plastics went from elephant saviors to eco-villains

- Plastics are demonized for eroding the environment and endangering human health, prompting many to wonder if we'd be better off without them.

- While the benefits of plastics may outweigh the costs, the costs are real and growing: Pollution is piling up and the health effects of chemical additives claim tens of thousands of lives while robbing trillions of dollars from the global economy.

- Plastics aren't going anywhere, leaving us to figure out how to live with them sustainably. That means maximizing their benefits while minimizing the costs.

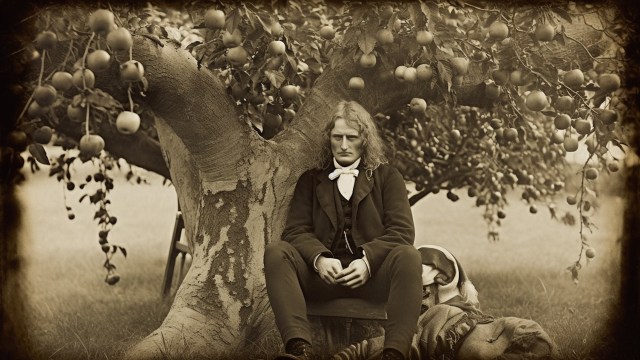

It was 1869, and something needed to be done.

With the price of ivory skyrocketing, billiard ball manufacturers were scrambling for an alternative. The prized material derived from elephant tusks was being used to craft such things as knife handles, piano keys, dice, dominoes, chessmen, and yes, billiard balls. Now, with elephants growing scarce from overhunting, the wonder material was becoming difficult to procure and unreasonably expensive. After all, one tusk would yield just four or five balls. Leading pool table manufacturer Phelan and Collender offered $10,000 ($225,000 today) to any inventor who could discover a replacement for ivory.

Albany inventor John Wesley Hyatt answered the call, molding together camphor, nitrocellulose, and alcohol under extreme pressure. His concoction, called celluloid, was one of the first synthetic plastics. While Hyatt’s creation proved an unwieldy material for billiard balls — insufficiently durable and mildly explosive when struck — it inspired others to formulate something better. A few decades later, American chemist Leo Baekeland came up with the petroleum-derived Bakelite. It became the first commercially successful synthetic plastic, and very likely saved elephants from extinction.

More than a century later, this story has morphed into an intriguing irony…With their creation, plastics probably saved countless species — both plants and animals — from extinction. Derived from byproducts of fossil fuel production, which had previously gone unused, the invention of synthetic plastics meant that humans no longer had to pillage the living natural world to produce various products for a technologically advancing global society. Fast-forward to today: Plastics are demonized for eroding the environment and endangering human health, prompting many to wonder if we’d be better off without them.

Plastics are made of polymers, long chains of repeating macromolecules. They can have various properties depending upon their chemical ingredients, but they all generally can be heated and molded into a wide variety of shapes at minimal cost. They’re also quite durable, hence their immense usefulness.

It is not an understatement to say that plastics enabled the technological growth that defines modern society, providing the forms for appliances and electronics. (Imagine if all electronics were made of metal or wood…) Look around you and you’ll notice that plastics are everywhere. PET, polyethylene terephthalate, is in your food containers and your clothing. HDPE, high-density polyethylene, makes milk and laundry detergent containers. PVC, polyvinyl chloride, is in pipes and medical devices. LDPE, low-density polyethylene, makes plastic bags. PP, polypropylene, is in food packaging and diapers. PS, polystyrene, makes up styrofoam cups and plates as well as various home construction materials. These six types account for 90% of yearly plastic production, which hit 460 million metric tons in 2019.

The problem now, as almost everyone knows, is that once plastics are produced, they don’t really decompose. Rather, they just break down into smaller and smaller bits — microplastics and even nanoplastics. These pervasive particles pollute pretty much everything, including drinking water, soil, living tissues, and even our blood, with deleterious effects, the full extent of which remains unknown.

Moreover, despite claims that plastics are recyclable, really only PET and HDPE (types 1 and 2 in North America) can be readily reused. In total, only 9% of plastic is melted and reformed. The rest goes into landfills or the wider environment.

Plastic pollution

What is the effect of omnipresent plastic pollution? According to the Minderoo-Monaco Commission report on Plastics and Human Health, published in 2023, the yearly economic cost reaches into the trillions of dollars. Plastic’s nefarious reach poisons human health, climate, agriculture, waterways, oceans, and wildlife.

According to the authors of the report, plastic additives may be the most pernicious. These substances augment plastics to make them more useful to consumers: stronger, more pliable, less flammable, non-stick, etc. However, large observational studies and research in lab animals indicate they are harming human health.

The substances could be increasing cancer rates, reducing birth weights, inhibiting antibody responses to vaccines, raising blood pressure, and contributing to infertility. These compounds include polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE), phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), and per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Philip J. Landrigan, a professor, pediatrician, and Director of the Program for Global Public Health and the Common Good at Boston College, is the lead author of the Minderoo-Monaco Commission report. He spoke with Big Think about the potential harms of plastic additives.

Landrigan was a pediatrician during the 1970s, when lead in gasoline, paints, and toys was secretly poisoning children. He says chemicals leaching from plastics constitute a similar threat: As they’re not chemically bound to the plastic matrix, they can easily escape into the environment. PBDEs, added as flame retardants in furniture and other products, have been found in house dust and are neurotoxic, he says.

“The thousands of chemicals in plastics—monomers, additives, processing agents, and non-intentionally added substances—include amongst their number known human carcinogens, endocrine disruptors, neurotoxicants, and persistent organic pollutants,” Landrigan and his fellow authors wrote in the report.

Given these negative effects, it may seem as if plastic is a fire-breathing dragon. While it began as an ally, it has now turned against us. If we don’t get the dragon back under control, it could spell our downfall.

To respond to threats from plastics, the experts on the Minderoo-Monaco Commission called for a Global Plastics Treaty comparable to the Paris Climate Agreement to combat climate change. As part of the treaty, they insist that a “cap on global plastic production with targets, timetables, and national contributions” is needed. Global plastic use is estimated to nearly triple by 2060.

But while other experts acknowledge that plastic waste is a problem, they counter that plastics’ harms to health are so far unknown.

“The truth is that determining the possible health consequences of nanoparticle exposure is a more challenging problem than going to the moon,” Dr. Joe Schwarcz, a chemistry instructor at McGill University and Director of the institution’s Office for Science and Society, told Big Think in an email.

“Feed phthalates to rats and you can track what happens. But that doesn’t tell us anything about a risk to a child who plays on vinyl flooring that has phthalate plasticizers or chews on a PVC duck that has been plasticized.”

Although Landrigan admits that the pernicious effects of plastics are often invisible in a clinical setting, he says they are very real. Findings suggest tens of thousands of premature deaths due to heightened rates of cardiovascular disease, a few points of IQ loss in children on average, and thousands of cases of infertility, particularly in males. These add up, causing societies to stagnate.

The hidden benefits of plastics

Still, plastics’ harms must be compared with their incalculable benefits to health, and yes, even the environment.

“The pharmaceutical, personal care product, sporting equipment, clothing, food production and electronics industries could not exist without the use of plastics. Neither could airplanes, cars, hospitals, cell phones, or sex toys,” Schwarcz wrote in an article. “The benefits of plastics greatly outweigh any associated risks, but those risks are not zero.”

Plastics allow clean drinking water to be safely transported to areas where infrastructure is absent or compromised. Their use in food packaging reduces food waste and food-borne illnesses. Single-use plastics are indispensable to modern medicine. Studies repeatedly show that disposable sanitary products are much less likely to transmit infection than re-used ones because cleaning isn’t perfect. Plastics are used to make IV tubes, dissolvable stents, blood bags, and syringes — all essential for saving lives.

Owing to their light weight, plastics make vehicles and aircraft more fuel efficient, reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions. Their widespread use in clothing — more than 60% of the fibers produced worldwide are synthetic — means that animal furs are unnecessary and we don’t need to get all our textiles from farming silk and cotton. We also don’t require tracts of rubber plantations when synthetic rubber is available, thus preventing deforestation.

“Consider what the planet would look like if all plastics used for rubber, textiles, and wood finishes had to be sourced from renewable resources,” Angela Logomasini, an adjunct fellow at the Competitive Enterprise Institute specializing in environmental risk, wrote. “If we switched to paper over plastic, we would need more forests to harvest timber, and shifting to metal food containers over plastic would require more mining. As a result, we would need more pesticides, water, and energy to access plastics from renewable resources.”

In short, synthetic plastics prevent widespread habitat destruction.

“The collective demand for land to meet humanity’s demands for food, fuel, and other products of living nature is — and always has been — the single most important threat to ecosystems and biodiversity,” Logomasini added.

It’s for this reason that bio-plastics, plastics made from renewable feedstocks such as corn, might never supplant synthetic plastics, even though scientists have been working on them for decades. These alternatives do decompose much more quickly in the environment, on timelines of months or years rather than centuries. However, they require much more natural resources to produce — so much that they might be even more environmentally intensive. One study found that replacing all synthetic plastics with natural ones would increase worldwide water demand by 3 to 18%.

While Landrigan told Big Think that he loves the concept of bioplastics, it’s still too early to see if they will work. “The devil is in the details,” he said.

Maximizing benefits and minimizing costs

So if plastics are so integral to human society and likely the best option we have for the health of both humans and the natural world, how do we keep their environmental costs in check? Plastic waste, after all, is piling up.

Landrigan recalled visiting Africa and seeing plastic bags blowing around everywhere like tumbleweeds. China stopped being the leading repository for the world’s plastic waste in 2018 after implementing an import ban. So now, spent plastics are being shipped to other countries, many of them poor and less developed.

Doing away with plastic bottles would be a good start. More than 500 billion are produced and sold each year. Other single-use plastics also need to go, Landrigan says. And the dangerous additives should be phased out.

But ultimately, scientists may need to provide a solution. Saliva from plastic-eating worms could be used to decompose plastics in the environment. Rapidly degrading plastics could be utilized for fishing nets. And new processes that make recycling more types of plastics economical could drastically reduce demand for virgin materials. Last year, researchers from the University of Wisconsin described in the journal Science a novel chemical method to transform low-value plastic waste into high-value materials, essentially spinning straw into gold.

George Huber, a professor of chemical and biological engineering, and one of the architects of the breakthrough, was effusive.

“There are so many different products and so many routes we can pursue with this platform technology,” he said. “There’s a huge market for the products we’re making. I think it really could change the plastic recycling industry.”

Plastics aren’t going anywhere, so we will have to learn to live with them sustainably. That means maximizing their benefits while minimizing the costs.