Why monopolies don’t always harm the economy

- A recent study examined the long-term economic effects of industries trending toward oligopoly and monopoly.

- The results found that increased market concentration was not correlated with price hikes — a negative consequence economists would expect to see in monopolies and oligopolies.

- Still, the study author noted that antitrust regulations have their place.

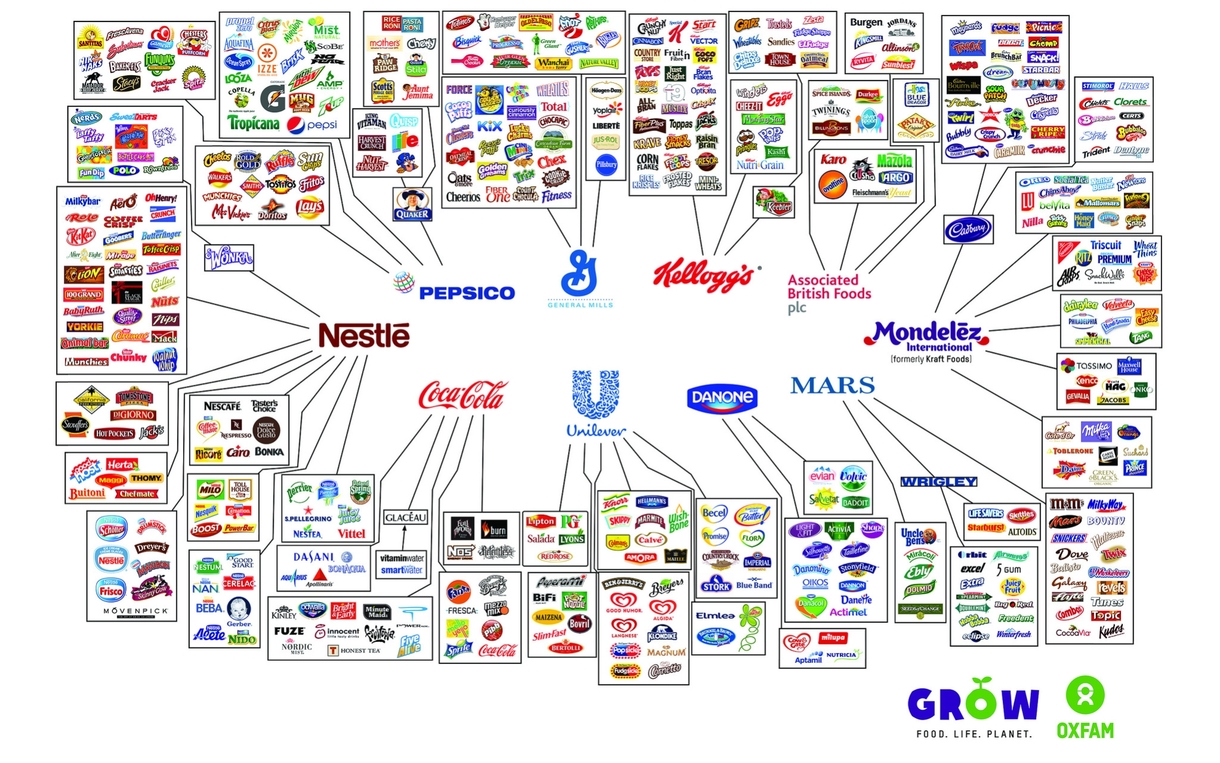

What is one thing Verizon, The Walt Disney Company, and Southwest Airlines have in common? All conduct business in highly concentrated industries, in which a handful of major players have wielded increasingly concentrated power and market share over recent decades.

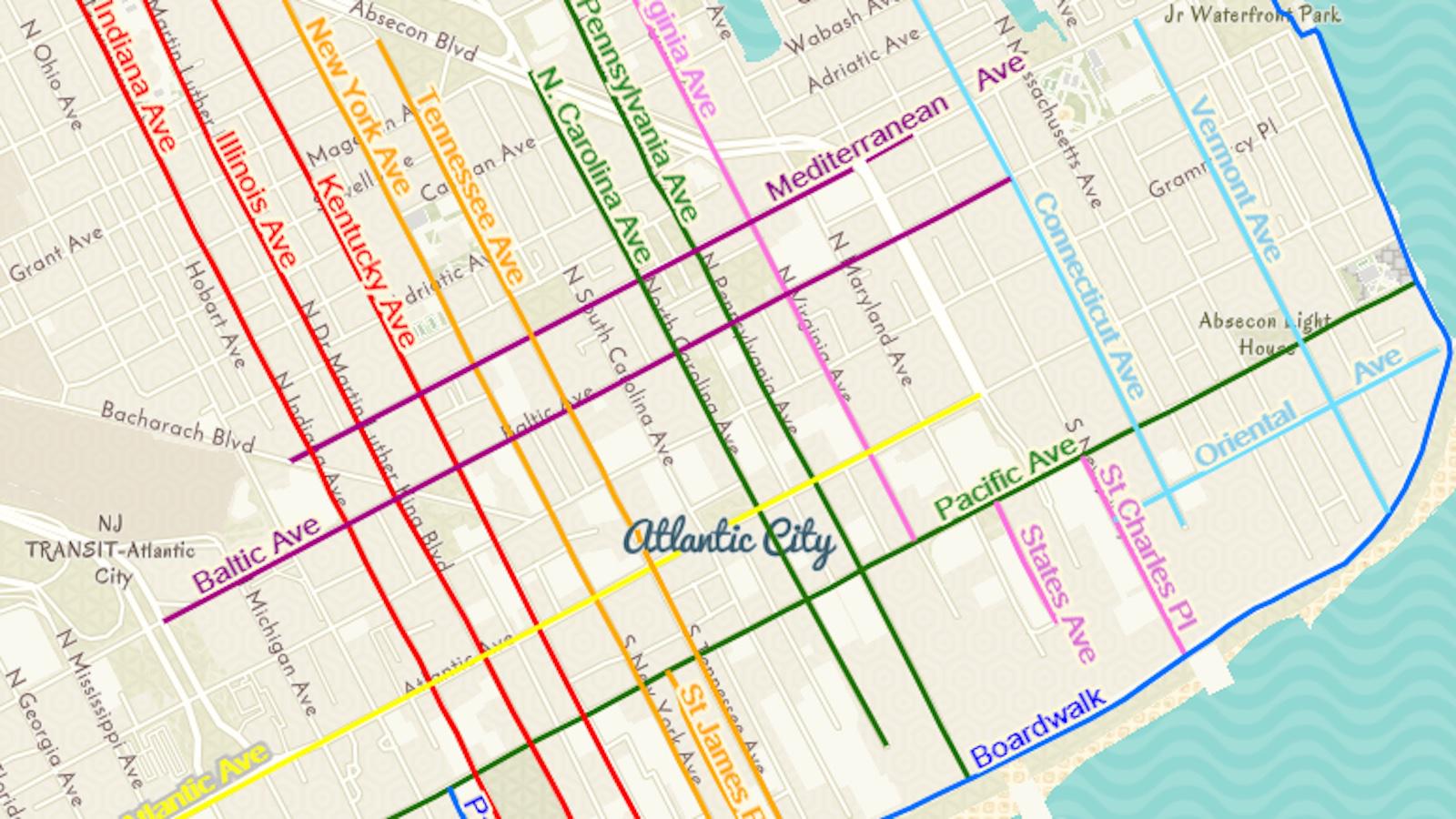

As you might recall from high school economics or a certain board game, monopolistic markets can damage the broader economy. After all, if one entity in an industry wields outsized market power, then you’re likely to see prices rise, workers get the shaft, and consumer surplus begin to fall.

But has this actually happened in recent decades?

A new study published in the American Economic Journal: Microeconomics by Georgetown professor Sharat Ganapat aimed to find out. The results, which have limitations, suggest that the increasing concentration of industry in the U.S. over recent decades hasn’t been as harmful as you might expect, and that monopolies and oligopolies might even have brought some benefits to the national economy.

For those who can’t quite remember economics class, economists are often wary of monopolies coming into existence. Unlike smaller firms in a competitive market, monopolies can dictate prices by controlling the supply of the goods they provide. If the monopoly is looking to maximize its own profits, as many economists presume, it has an incentive to produce fewer goods at a higher price than a smaller firm in a competitive market. The monopolist can also charge a higher price.

Oligopolies are similar to monopolies, but they feature a handful of firms dominating a market rather than just one. Oligopolies and monopolies can produce similar problems, though entities in oligopolies tend to hold less market power. To keep markets competitive, many nations have established antitrust laws that prohibit large companies from, for example, pricing out smaller companies in certain geographic regions.

Markets don’t always follow theory

To illuminate the effects of market concentration, Ganapati examined census, pricing, and industry data from 1972 to 2012 in the U.S. The results showed that market concentration was not correlated with price hikes. Instead, market concentration was correlated with increased output — a significant finding, considering that economists would generally expect to see reduced output in both oligopolies and monopolies.

What explains the findings? Ganapati suggests that “superstar” firms outperform their rivals in productivity and innovation, enabling them to dominate their industries. In an interview with the American Economic Association, he used the success of Walmart to illustrate his superstar hypothesis:

“Walmart is a great example of what’s going on. They spent billions of dollars in the ‘80s and early ‘90s computerizing their entire infrastructure operations. It gave them an almost insurmountable lead for 20 years in the big-box store industry, letting them kill off rivals such as Sears and JCPenney.”

But it’s not all good news. Although the data suggest that many large firms earned their top rank through innovation and productivity improvements, they also employed fewer workers. These workers were typically paid better than average, but their earnings didn’t reflect the growth of their companies.

“A 10 percent increase in the market share of the largest 4 firms is correlated with a 1 percent decrease in the labor’s share of revenue,” Ganapati noted.

Beyond labor concerns, there are industries where contracting market power is understandably concerning to economists. For example, market concentration in health care has led to price increases. Another concern: Even in industries where market concentration didn’t lead to hikes, the savings from productivity haven’t always been passed on to customers.

A role for regulation

None of these findings suggest that the old concerns over monopolies and oligarchies are obsolete and that we should welcome market concentration. Rather, the research suggests that monopolies and oligopolies don’t always cause the damage they’re capable of causing. Ganapati concludes:

“…taking the superstar firm hypothesis seriously does not imply that antitrust authorities should be powerless. Dominant firms may entrench themselves and use their newly dominant market positions to engage in anticompetitive behavior. Natural monopolies can give way to anticompetitive monopolies that act to raise prices and squelch innovation. Monopolies may be taking a bigger share of productivity innovations for themselves and only passing a small share of the gains to the consumer. Effective regulators may want to force monopolies to share a greater share of their surplus with the public.”