Memes as propaganda: 22 devious techniques used to weaponize social media

- The advent of the internet gave rise to computational propaganda: the use of automated processes to spread misinformation for specific purposes.

- Memes have proven to be a particularly effective tool for computational propagandists, allowing them to convey complex ideas with minimal effort.

- Ever since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, researchers have been trying to understand how memes originate and spread. Now, a recent study is calling for uniform terminology.

The form and function of memes has evolved drastically as the internet and its users matured. Currently, they can be defined, extremely loosely, as a set of standardized visual templates that, combined with one or two short sentences, quickly convey an idea or feeling which can then be applied to different situations.

When it comes to memes, examples are clearer than explanations. In “Bad Luck Brian” memes, sentences describing unfortunate circumstances are placed over an awkward school picture, while the “One Does Not Simply” meme uses a still from the film The Lord of the Rings to describe tasks that are much more difficult than others make them out to be, i.e. destroying the One Ring.

When memes first started gaining popularity in the late 2000s, most were harmless and relatively uncontroversial. Back when cell phones were not yet advanced enough to support playing YouTube videos, platforms like Reddit and 9GAG allowed their users to browse through mindless entertainment before falling asleep.

However, as time went on and templates became more and more recognizable, internet memes developed into something more than just a silly joke. Thanks to their ability to communicate complex ideas quickly and efficiently, they are now being used as a form of propaganda, influencing our opinions and actions without us even knowing it.

Propaganda in the information age

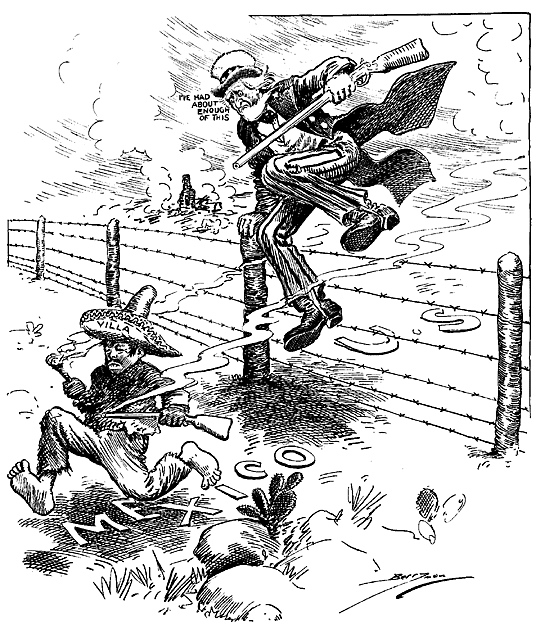

Propaganda is as old as humanity itself. In the Arthashastra, an ancient Sanskrit treatise written during the third century BC, the polymath Chanakya discussed how rulers can use misinformation to govern society and wage war; Chanakya’s student, Chandragupta Maurya, relied on his mentor’s understanding of propaganda to found the Mauryan Empire.

The art of deception reached new heights with the invention of the printing press, which allowed medieval European publishers to copy and distribute information to large numbers of people. In the coming age of revolutions, political pamphleteers — concerned not with accuracy but mobilization — learned how to inspire action by playing off the emotions of their readers.

The next chapter in the history of propaganda took place during the 20th century, when totalitarian leaders in Germany and Russia found that, by controlling media outlets and silencing opposition movements, they could radically alter the way their subjects distinguished fact from fiction, not to mention right from wrong.

Today, propaganda is evolving yet again. Thanks to the internet and social media, propaganda is not only more common but also harder to fight. After all, digital information spreads quicker than printed texts or even word of mouth, and personalized news feeds and advertisements reduce people’s exposure to contradicting beliefs, causing them to become further entrenched in their own.

The age of information also gave birth to an entirely new form of propaganda that could not have existed before: computational propaganda, or the practice of using automated processes to spread misinformation online. Computational propagandists use a variety of media, from text to videos and — yes — memes. Lots and lots of memes.

Memes as political propaganda

There are several explanations for why memes became instruments of propaganda. Aside from the fact that they can communicate complex ideas quickly, they also require minimal effort to make and interpret. They can easily be shared online and have huge potential to go viral, making their spread and influence almost impossible to counter.

While our academic understanding of the medium is still developing, propaganda memes have already had a noticeable effect on society. According to several studies focused on the U.S., memes created by domestic and foreign propagandists played a key role in both the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential elections, influencing the public’s opinion of the candidates and affecting voter turnout.

The 2016 election in particular alarmed scholars about the power and danger that propaganda memes wield in today’s interconnected civilization. Since then, numerous studies have attempted to break down how memes communicate ideas, influence opinions, and spread through digital networks — all in the hope of minimizing their corrosive influence.

Different studies have approached propaganda memes from different angles. Some, like this study from 2017, focused mostly on the structure of the online environments in which memes are created and shared with the intention to develop methods to identify bots, malicious accounts and other forms of inauthentic behavior on the web.

Others, like this one from 2019, took a closer look at the memes themselves, specifically at the language they use to get their points across. One paper from 2017 classified memes into four distinct classes: trusted, satire, hoax, and propaganda. The study claimed that the category of any meme could be ascertained through studying its tone, voice, and sentence structure.

The body of academic literature on propaganda memes has grown significantly over the past few years. However, the field of study still lacks a uniform terminology. To that end, an interdisciplinary team of researchers reviewed previous studies to create a list of 22 common propaganda techniques that can be used to recognize and better understand nefarious memes.

The team — consisting of meme and mathematics experts assembled from Sofia University, King’s College London, Qatar Computing Research Institute, Sapienza University Rome, Facebook AI, and the University of Padova — presented its findings in a paper which, though not yet peer-reviewed, argues that memes need to be studied both textually and pictorially.

The workings of propaganda memes

As part of their study, the researchers collected some 950 memes that were sourced from private Facebook accounts and were selected for their quality as well as subject matter. According to the paper, the majority of memes were about political topics such as the COVID-19 pandemic and gender equality — two major obsessions of the alt-right.

Once these memes had been assembled, the researchers formulated 22 distinct propaganda techniques that their creators might have employed. To do so, they drew from at least five previous studies with similar goals. Of the 22 techniques, 20 could be applied to both images and text, while 2 served for labeling images only.

Some of these techniques should sound familiar already, such as appeal to fear / prejudices (5): “seeking to build support for an idea by instilling anxiety and/or panic in the population towards an alternative,” as well as causal oversimplification (10): “assuming a single cause or reason when there are actually multiple causes for an issue.”

Some of the less obvious techniques include:

- thought-terminating cliche (12): words or phrases that discourage critical thought and meaningful discussion about a given topic

- whataboutism (7): the attempt to discredit an opponent by charging them with hypocrisy without directly disproving their argument

- black-and-white fallacy (13): the notion that a problem only has two solutions

A couple items describe techniques you might not have known have definitions. Reductio ad hitlerum (14) is the practice of disapproving of an idea or action because it is popular among social groups that the majority of human civilization holds in contempt, like the Nazis or the KKK. Meanwhile, obfuscation (16) means being unnecessarily vague and confusing.

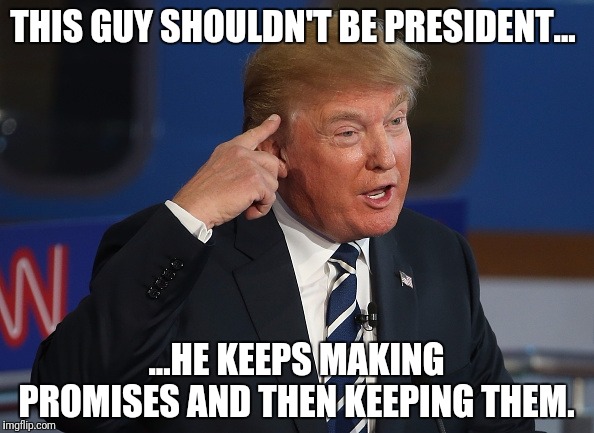

Let’s look at an example. At the start of the article, the researchers showed a number of political memes. One of these consists of two images: at the top, a photo of former U.S. president Harry S. Truman with the quote, “You can’t get rich off politics unless you’re a crook.” At the bottom, a photo of the Clintons, smiling, with the text, “We know.”

The origins of this meme are unknown. However, it is safe to assume that it originated during the 2016 presidential election as an attack on Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. The researchers can identify several propaganda techniques in this particular meme. The quotation, which may or may not belong to President Truman, is an appeal to authority (11).

The statement “We know” constitutes two additional propaganda techniques. It’s a thought-terminating cliche, discouraging discussion on whether or not the Clintons are indeed crooks. It’s also an example of smears (19), an attempt to damage or question someone’s reputation by propounding negative statements without compelling evidence.

The future of meme studies

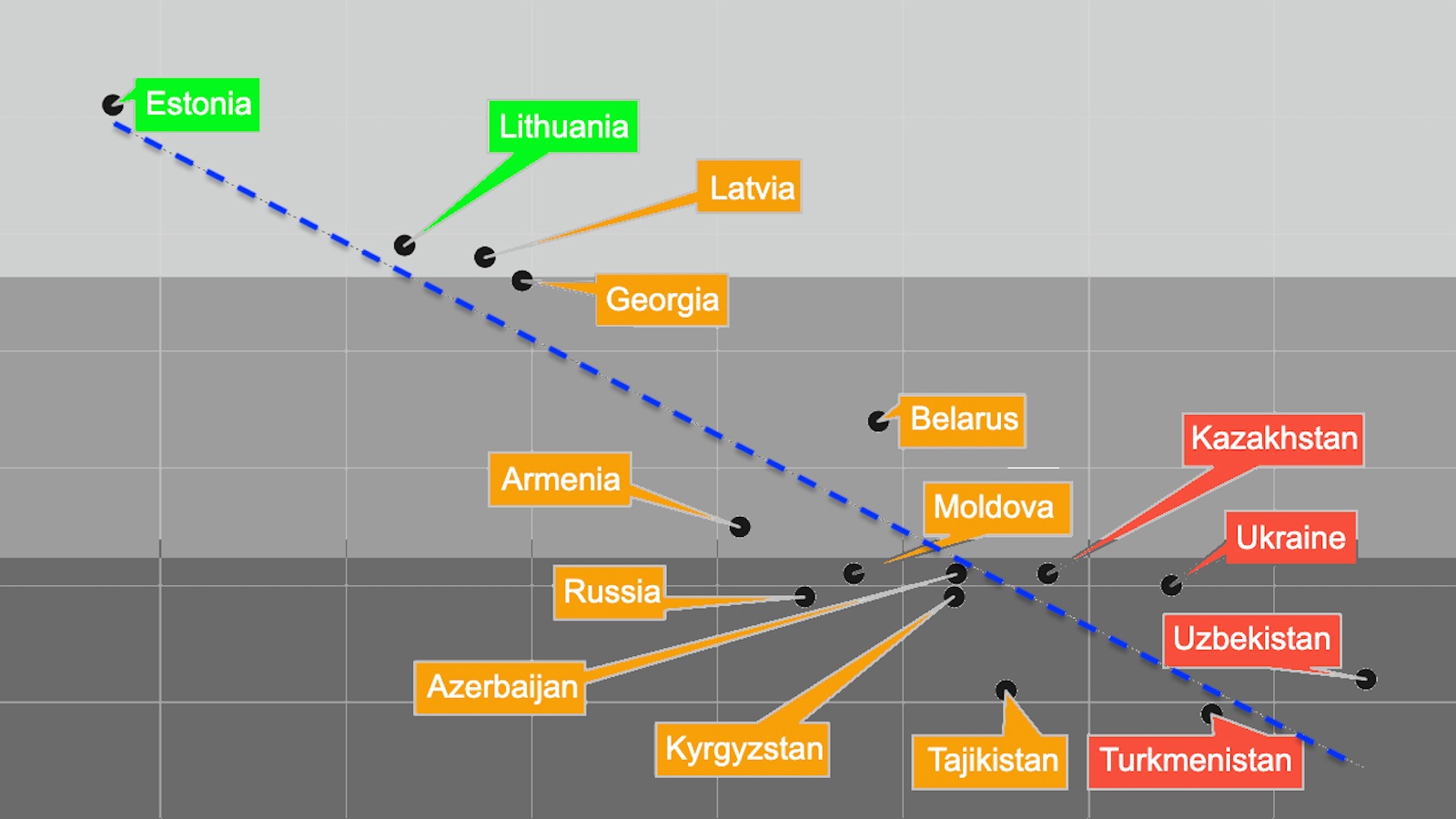

As part of their study, the researchers searched all of their 950 memes for traces of these 22 propaganda techniques. Every time a particular technique was used, they made a note of it. As a result, they were able to discover how often each propaganda technique is used, and which techniques are used more often than others.

According to the study, some of the most common propaganda techniques were smears, loaded language (1), and name-calling/labeling (2). Smears were found in about 63% of surveyed memes, loaded language in 51%, and name-calling in 36%. These techniques are typically used together, forming the most common sets of pairs and triples in the dataset.

The researchers were also able to get an idea of how many techniques the average propaganda meme employs. Most memes, they declare, use more than one technique. The highest number of techniques used in a single meme was eight, and the average number of techniques used in a meme was 2.61, implying that propaganda memes are more complex than we give them credit for.

Last but not least, the study revealed that the vast majority of memes make use of propaganda techniques that can apply to both images and text. As such, they stress that future studies should focus on both the textual and visual components of memes. The article calls for a multimodal approach: an approach that “effectively [exploits] all information available.”

While the researchers answer key questions about the workings of propaganda memes, they also raise concerns of their own. Of the 22 techniques discussed in the article, not all apply exclusively to propaganda. Propagandists may often appeal to authority to make their points, but so do scholars when they cite previous studies in their article.

Although these definitions will have to be finetuned before they can be adopted by others, the researchers are absolutely right in their opinion that this still-developing research area would benefit from having a uniformly adopted terminology that other researchers can use to contextualize their own findings within the larger body of scientific literature.