Highway fatality signs may cause more car crashes

- Twenty-eight states use digital highway signs to display road fatality statistics to motorists, with the well-intended goal of reducing accidents.

- Researchers found that automotive crashes actually increase within ten kilometers downstream from signs displaying these messages, potentially causing an additional 17,000 crashes in the U.S. each year.

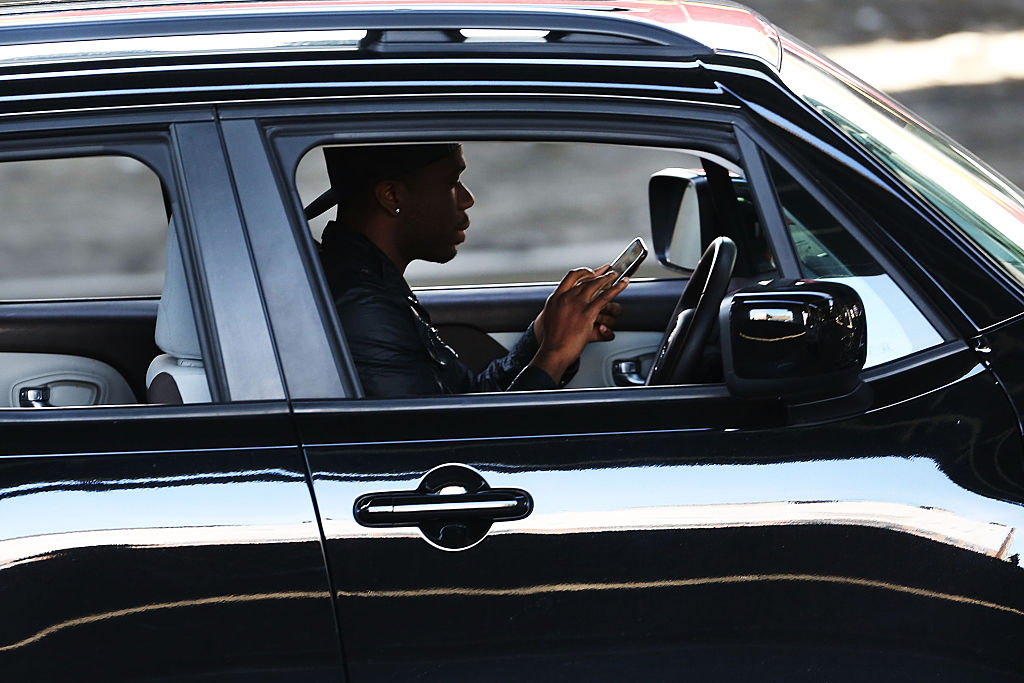

- It seems that these messages only serve to distract motorists. Distracted driving is the most common cause of car crashes.

You may have seen them when driving on the highway: large digital signs broadcasting messages about car safety, with the goal of preventing crashes and saving lives.

“Santa is watching. Drive sober,” a Delaware sign blared during the holiday season. “That seatbelt looks good on you,” declared another. “May the 4th be with you. Text I will not,” read a different sign to reach the Star Wars fans out there. Others simply showcase traffic fatality statistics as an ominous warning.

These messages are well-intended and occasionally chuckle-worthy, but according to a recent analysis published to the journal Science, in certain circumstances, they can backfire horribly.

Unintended consequences

Researchers Jonathan D. Hall at the University of Toronto and Joshua Madsen at the University of Minnesota teamed up to study the effects of the Texas Department of Transportation’s program to display up-to-date statewide road fatalities to motorists on specific highway dynamic message signs for one week each month. Twenty-eight states have similar programs, but Texas’ is ideal for scientific study because of its duration (dating back to August 2012) and the fact that it’s regularly scheduled with the same signs.

“This allows us to measure the impact of the intervention, holding fixed the road segment, year, month, day of week, and time of day,” Hall and Madsen commented.

With data on 880 of these signs and statistics on all road crashes in Texas from the beginning of 2010 through the end of 2017, the researchers were able to distill the effects of broadcasting these messages to Texas drivers. They compared the number of crashes ten kilometers downstream of signs when they were being used to display fatality statistics with the number of crashes when they were being used normally — to warn motorists of slick road conditions or of upcoming traffic, for example.

The result was stark and surprising. Crashes increased by 4.5% when the traffic fatality messages were shown.

“The effect of displaying fatality messages is comparable to raising the speed limit by 3 to 5 miles per hour or reducing the number of highway troopers by 6 to 14%,” the researchers noted. “Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that this campaign causes an additional 2600 crashes and 16 fatalities per year in Texas alone, with a social cost of $377 million per year.”

Extrapolating to the rest of the states which utilize this messaging, the strategy might cause an additional 17,000 crashes and 104 fatalities per year, with a total social cost of $2.5 billion per year, the authors calculated.

“In-your-face” is also distracting

The likely reason this signage is associated with additional crashes is somewhat obvious: it’s distracting.

“These ‘in-your-face,’ ‘sobering,’ negatively framed messages seize too much attention, interfering with drivers’ ability to respond to changes in traffic conditions,” Hall and Madsen wrote.

Supporting this explanation, the authors found that displaying higher fatality numbers was linked to more crashes. Moreover, the deadly effect was more pronounced closer to the signage and when roads had more complex layouts.

Interestingly, Hall and Madsen discovered that when the number of displayed traffic fatalities were lower — under roughly 1,000 — there were fewer crashes downstream of the signs compared to when the signs were used normally. Drivers seemed to tune out these numbers and remained focused on the road.

The study’s chief takeaway? Displaying complex, moralizing messages on highway signs seems to be the wrong strategy to reduce car crashes. Distracted driving is commonly considered to be the most frequent cause of automotive accidents. Capturing motorists’ attention with morbid statistics while on the highway appears only to worsen that status quo. It may be wise to cease these campaigns altogether, the authors conclude.