En-ROADS: A powerful, interactive climate model for predicting temperature rise

- There are many different climate models. En-ROADS is one of the better ones.

- This interactive model allows you to adjust variables, such as the extent of renewable energy or electric cars, to see what impact they will have on global temperature.

- Smart policies are those that provide the “biggest bang for the buck.”

Understanding climate is a tricky proposition because it is a long-term phenomenon that involves so many variables that they cannot possibly all be evaluated or even measured. For example, we cannot really predict cloud formation or volcanic activity. Therefore, we must rely on models that make many unverifiable assumptions. At best, they can take into consideration some of the physics that influences climate and a consensus of the assumptions regarding climate.

As a result, there are a number of models that predict a variety of outcomes, depending on how the modelers selected variables. This can be baffling even to real scientists, let alone to politicians chosen for that elusive quality of “electability.”

So, what are concerned citizens to do? Should we compost our food scraps, buy a Tesla, or what? Fortunately there is a well-regarded, scientific model that lets us answer some of those questions: the En-ROADS model, developed by Climate Interactive, Ventana Systems, and MIT’s Sloan School.

The En-ROADS climate model

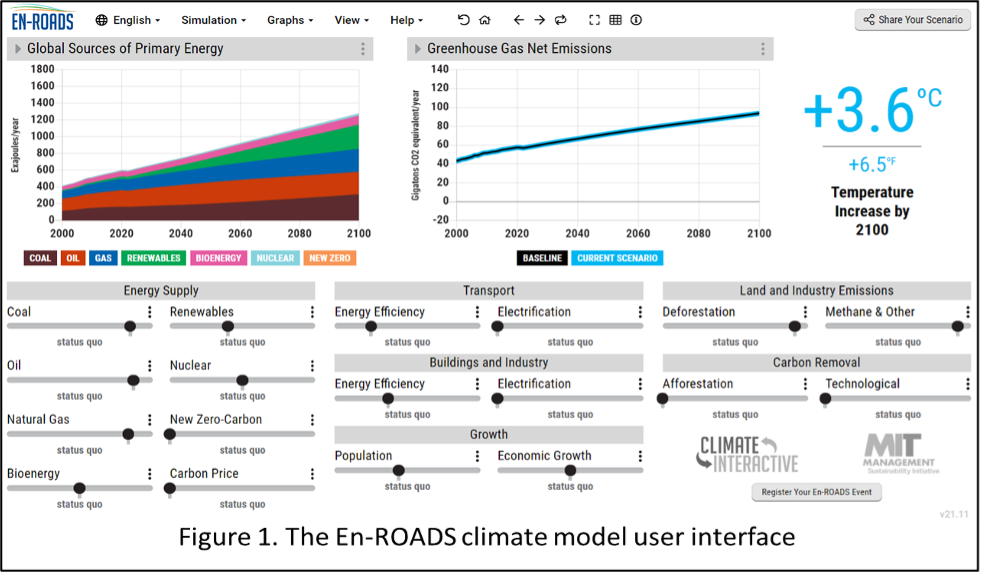

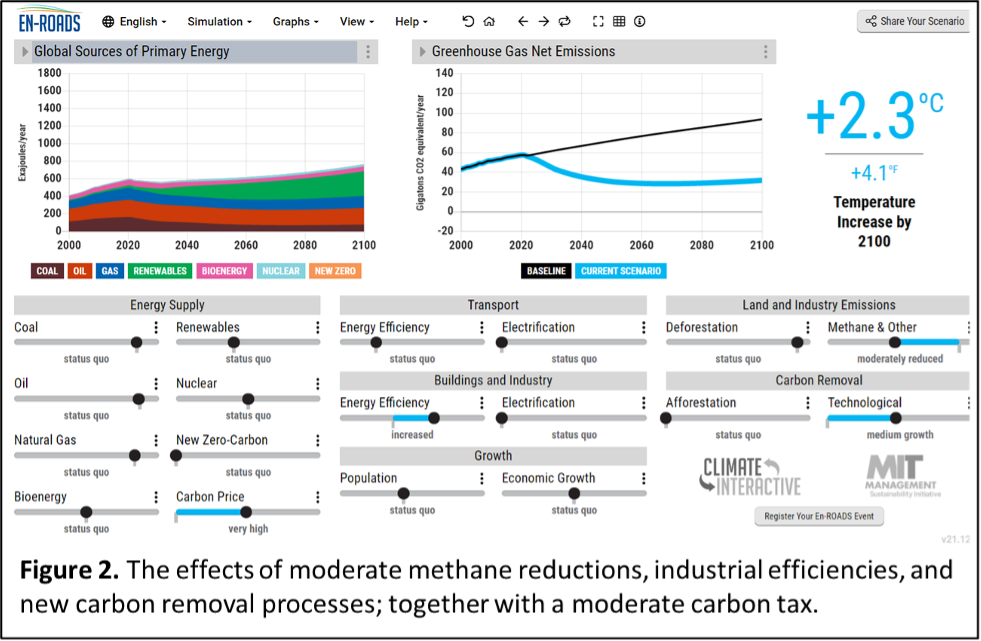

What is unique about En-ROADS is that it is interactive, with a simple interface that allows each user to explore most of the variables that are thought to affect climate. The figure below shows the En-Roads interface.

The top row shows the sources of energy over time (first graph), greenhouse gas emissions (second graph), and the expected temperature rise through the year 2100 – that is, through the end of this century.

The slider bars in the lower half of the figure allow the user to manipulate a variety of variables to see what their effects are. Clicking on the variable allows the user to see what assumptions are made for each action and reveals more slider bars that change variables. For example, clicking on “Renewables” reveals, in part, this explanation: “Encourage or discourage building solar panels, geothermal, and wind turbines,” and the slider bars allow the user to change parameters such as the imposition of a tax or subsidy.

The variables assume that the actions are taken globally, not just in the United States. Thus, any actions that are implemented only in the U.S. will have much smaller effects. The current values for each variable are the baseline and result in a predicted rise of 3.6° C by 2100 if no new actions are taken. The accuracy of this model is unlikely to be better than ±10%, in other words ±0.36° C. So, in this article, we will call any effect that results in less than a change of ±0.36° as being negligible.

What are the best climate policies?

The Biden administration wants trillions of dollars to enact the “Green New Deal,” which includes large cash incentives for wind turbines, solar panels, and electric cars. Therefore, it is instructive to see what the effect would be if we subsidized renewable energy globally to the maximum extent possible. If we slide the slider for “Renewables” all the way to the right, the temperature drops only 0.2° C by the end of the century. That’s negligible. How about electric cars? Slide the “Transportation Electrification” bar all the way to the right. The drop is 0.1° C — again, negligible. How about punitive taxes on coal? Still negligible at 0.2° C. Planting more trees – negligible. Bioenergy has no effect at all. Thus, the important bottom line: Much of what is in the Green New Deal has little scientific justification.

Which measures could have an appreciable effect? There are a few. Extreme reductions in methane emissions result in about half a degree drop. This would not be easy to accomplish but is worth exploring. Carbon removal could result in a drop of about 0.4° C. Unfortunately, we do not currently have scalable technologies for this, but again, exploration could be useful; science and technology are powerful when they are focused and well-funded. Highly improved industrial energy efficiency would also result in a 0.4° C drop.

The big winner according to En-ROADS is a very large carbon tax. At a price of $250 per ton of CO2 generated, En-ROADS predicts a reduction of a full degree. But a carbon tax is not part of the Build Back Better proposal and for good reason: such a tax likely would stifle the economy and would disproportionately impact the poor.

The good news is that investing in reasonable methane reduction, industrial efficiency, and carbon removal technologies, along with a moderate carbon tax on a global scale could result in a drop of 1.3° C in the expected temperature rise. The figure below shows the effect of these changes.

An inconvenient truth

The bad news is that this still means a rise of 2.3° C. And that is if the entire world were to implement these actions; acting alone, the United States will spend trillions and have a negligible impact.

The hard choices involve creatively and fairly implementing a carbon tax, telling the truth to the public, and providing for adaptation. We know that flooding can be abated; Amsterdam and much of the rest of Holland have been below sea level for centuries. Drought can be abated through efficiency and better water management, including desalination and long-distance pipelines. Buildings can be hardened against storms, and better warning systems can alert people to approaching adverse weather.

Finally, it must be noted that the temperature rise, while significant, will be gradual and will not have sudden inflection points. Thus, the notion that we are approaching some “tipping point” beyond which there will be a global catastrophe resulting in human extinction is simply insupportable. Let’s not panic but put our heads together and work.

Tom Hafer developed systems for neutralizing rockets and drones. He currently coaches teenage robotics teams. Henry I. Miller (@henryimiller), a physician and molecular biologist, was a Research Associate at the NIH and the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology. Henry and Tom were undergraduates together at MIT.