No more Medvedev, Tchaikovsky, or Dostoevsky: the pros and cons of cancelling Russian culture

- Putin’s indefensible invasion of Ukraine led foreign powers to formulate a wave of sanctions against Russia.

- Most sanctions target the country’s economy and political establishment, while others are aimed specifically at Russian art and culture.

- Although international opinion of Putin is at an all-time low, some wonder if ordinary Russians should receive the same treatment as their leader.

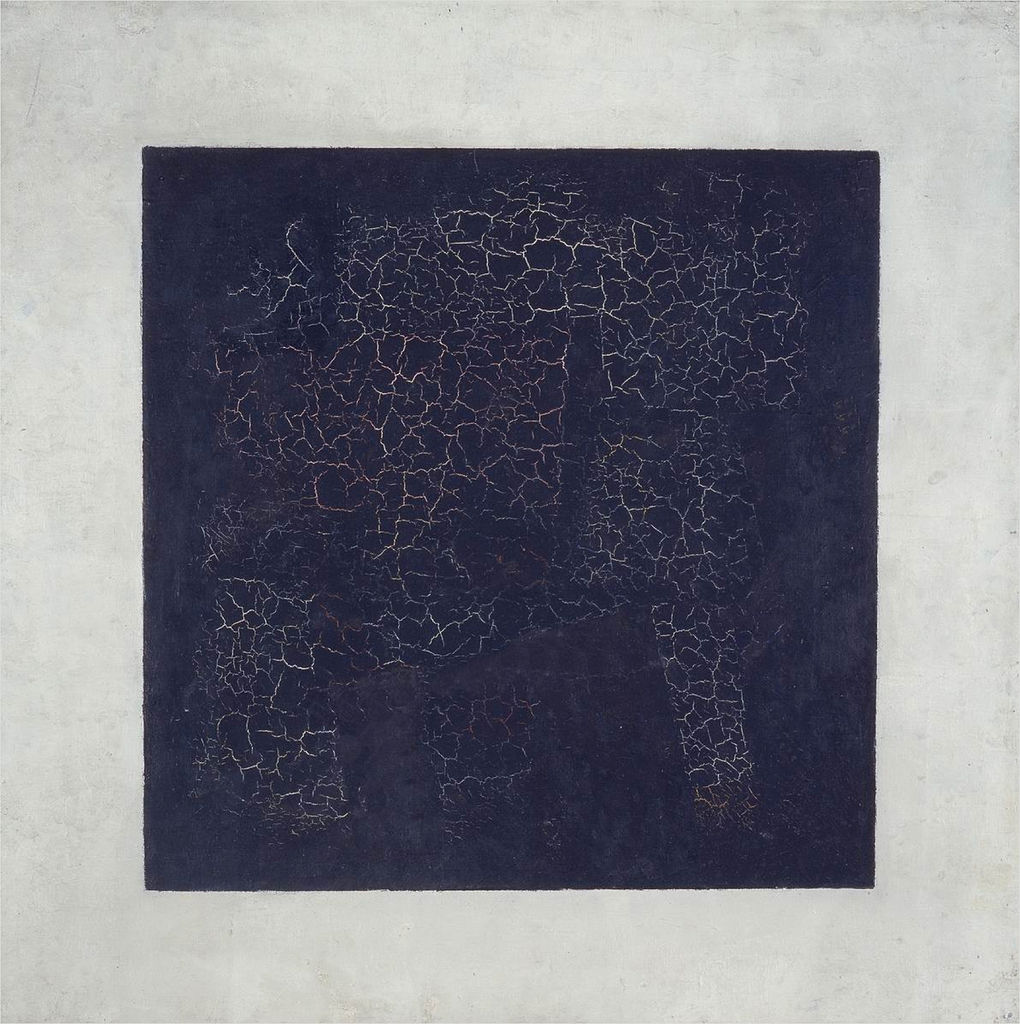

On March 3, the Hermitage Amsterdam sent out a short press release condemning Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine. The Dutch museum, which opened in 2009 with the goal of exhibiting artwork loaned from the State Hermitage Museum, also announced it would sever its ties with Russia. As a direct result of this decision, their latest exhibit, “Russian Avant-Garde: Revolution in the Arts,” closed down so paintings made by Kazimir Malevich and other modernists could be shipped back to the other side of the Iron Curtain.

The above is but one example of the many sanctions that Western institutions have leveled against Russia in the wake of Putin’s invasion. However, the disbanding of the Hermitage Amsterdam’s long-awaited exhibit differs from other sanctions in that it is aimed not at Russia’s economy or political establishment but the country’s art and culture. While international relations with the Kremlin are at an all-time low, not everyone is convinced Russia’s cultural heritage should be targeted with the same kind of ferocity as the man claiming to protect said heritage.

A day after the Hermitage Amsterdam made its announcement, the Dutch author and former Russia correspondent Pieter Waterdrinker tweeted a photo of Malevich’s famous painting Black Square. “This masterpiece by the Kyiv-born artist Malevich,” Waterdrinker tweeted, “will no longer be accessible to the Dutch public.” He implies the decision to close down the “Russian Avant-Garde” was narrow-minded, and many of his followers agree. In the comments, art lovers bemoan the museum’s temporary shutdown and wonder when Tolstoy and Chekov will be next.

In a sense, that fear already came true. Recently, the University of Milano-Bicocca in Italy tried to cancel a class on Fyodor Dostoevsky who, aside from writing universally loved stories like The Brothers Karamazov, also identified as a Russian nationalist on global issues. The cancellation was criticized by writer and guest lecturer Paolo Nori. “I realize what is happening in Ukraine is horrible,” Nori shared on Instagram. “But what is happening in Italy is ridiculous… Not only is being a living Russian wrong in Italy today, but also being a dead Russian.”

He’s not the only dead Russian to face a ban. The Cardiff Philharmonic in Wales decided not to play a piece composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

As for living Russians, Wimbledon announced in March they would ban tennis player Daniil Medvedev from the tournament if he did not openly denounce Putin — a move which could endanger friends and family in Russia. The subsequent decision to bar both Russian and Belarusian players was criticized by ATP and WTA tours, as well as by Novak Djokovic. “I will always be the first to condemn war,” the Serbian stated, but added that he “cannot support the Wimbledon decision… It’s not the athletes’ fault.”

The pros and cons of cancelling Russia

Sanctions aimed specifically at Russian art, culture, or nationality continue to cause controversy, but some would argue that desperate times require desperate measures. As the Moscow-based reporter Nick Holdsworth tells Big Think via email, Ukrainians “argue that until Putin is defeated and the last Russian troops have left Ukrainian soil total disengagement [from Russia] is not only necessary, but morally correct.” This desire to disengage predates Putin’s invasion; in 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky’s predecessor signed a law limiting the use of Russian in public life.

The law was not designed to attack Russians but rather to defend Ukrainians. As the Ukrainian-American writer and scholar Alexander Motyl explains in Foreign Policy, Putin has turned the Russian language into a weapon with which to erase the national identity of other Eastern European countries. The same, he tells Big Think, is true for Russian culture: “By identifying the fascist Russian state — and himself — with Russian language and culture, Putin has transformed the Russian language and culture into tools of the state, into vehicles of propaganda, legitimation, and aggression.”

According to Motyl, all Russians, including Putin’s critics, “are morally responsible for the fascist regime he has created. We insist that Germans should have opposed Hitler; by the same logic, we should insist that all Russians should have opposed Putin. Cancelling this morally complicit Russian society is both morally and politically right, just as cancelling Nazi society was right… Russian culture needs to be corrected, just as German culture was corrected, so as to make another Putin (or Stalin, or Lenin, or Peter the Great) impossible.”

Michel Krielaars, another former Russia correspondent from the Netherlands, is not so sure. He currently works as editor of a book supplement for the Dutch newspaper NRC, in which he looks at the Russo-Ukrainian war through the lens of classic Slavic texts. While Krielaars sympathizes with the Ukrainians and understands their anger over Russian aggression and war crimes, he remains adamant in his belief that much of Russia’s cultural production does not qualify as propaganda. Conversely, sanctions should be formulated on a case-by-case basis rather than a categorical one.

Obviously, from the Western perspective, Russians who have been vocal in their support of Putin — like the musical conductor Valery Gergiev or operatic soprano Anna Netrebko — should be sanctioned, while those who are brave enough to oppose him should not. The gray area, Krielaars suggests, lies somewhere in the middle: the artists, athletes, entrepreneurs, and other types of ordinary citizens who have remained silent about the Russo-Ukrainian War not because they sympathize with the Kremlin, but because they are afraid of losing their livelihoods or being jailed if they speak up.

At the end of March, the Moscow-based polling agency Levada Center revealed that 83% of Russians supported Putin’s actions as president. This frightening statistic has been featured in dozens of Western news reports, but Krielaars points out that those numbers should not be taken at face value: “When you receive a call from a national polling agency that knows your name, home address, and phone number, and asks whether you are with or against Putin, you obviously answer ‘yes,’ because you are afraid of the consequences.”

A society held hostage

“You don’t end wars through boycotting writers and musicians,” Krielaars concludes. He is reminded of the Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who in 1968 traveled to London with the Soviet State Symphony Orchestra. The musicians were unwelcome, for the USSR had invaded Czechoslovakia earlier that day. But when audiences saw Rostropovich play the music of Antonín Dvořák with tears streaming down his face, they cheered. The cellist’s silent protest was one of the greatest in history and would not have been possible if the UK had refused to let him perform.

Technically, Rostropovich was complicit in maintaining the Soviet Union — as was the Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who Rostropovich befriended and sheltered. Like the majority of children born after the October Revolution, Solzhenitsyn grew up a staunch communist who rejected his parents’ faith in favor of Marxism-Leninism. He served as a captain in the Red Army during World War II, only to be imprisoned for questioning Stalin in a letter sent to his brother. The book he wrote about his time in jail, The Gulag Archipelago, ultimately helped destroy the USSR.

Solzhenitsyn didn’t publish The Gulag Archipelago until it was safe for him to do so. After his release from prison, he and his collaborators spent years hiding the various copies of the book from KGB agents. “Not only was I convinced I should never see a single line of mine in print in my lifetime,” the author stated upon accepting the Nobel Prize for his work, “but, also, I scarcely dared allow any of my close acquaintances to read anything I had written because I feared this would become known.” Totalitarian regimes survive not only through popular support but also suppression of dissent.

In 2020, I wrote an article about the Hermitage Amsterdam for the Dutch newspaper Het Parool. The museum had suffered heavily during the coronavirus pandemic and was launching a fundraising campaign in order to survive. In the article, I argued the organization needed saving not only because it showcased incredible art but also because it was one of the few remaining places in the world that still showed a side of Russia that managed to escape the ever-growing shadow of its current president. It was, to borrow a Cold War phrase, a bridge between East and West.

While working on the article, I was reminded by a college professor who once told me that, in dealing with the Russian state, Western countries had to think not only of the present but also of the future — that is, of the inevitable point in time when Putin will be gone. The Kremlin likes to pretend this moment will never come, but it will. When it does, we have to be willing to enter a dialogue with the elements of Russian society that listen to reason. Not until the country is properly integrated on the world stage will we be able to prevent the rise of another Putin, Stalin, or Peter.