Here’s what being filthy rich in Europe looked like in 1000 BC, 1 AD, and 1000 AD

- Archaeological sites show that upper-class individuals from the Iron Age started living in bigger houses.

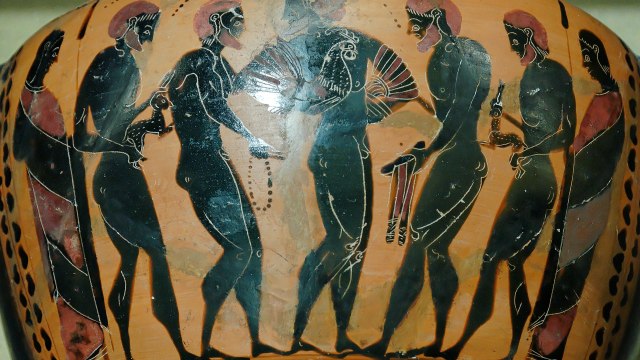

- During the final days of the Roman Republic, influential families would show off their wealth through art and banquets.

- In the High Middle Ages, feudal lords had complete economic and political control over their serfs.

To ask what it was like to be rich in the past is about more than comparing the lifestyles of modern-day billionaires like Elon Musk to Mansa Musa or Marcus Licinius Crassus. When you study the history personal wealth, you are also learning about the history of income inequality, and the economic developments that allowed these upper-class individuals to build their private fortunes.

According to the historian Peter V. Turchin, who relies on mathematical modeling to make sense of the societies past and present, those developments turn out to be cyclical rather than linear, with patterns in the global financial system repeating themselves across centuries. In other words, Musa and Musk may have more in common than you’d think.

Burial gifts from 1000 BC

We do not know a lot about daily life or income inequality at the start of the Iron Age, a time when Latin tribes first set foot on the Italian peninsula, and David — the very same David whom the Bible says defeated Goliath with a sling shot — is believed to have ruled over the United Kingdom of Israel. The general absence of written scripts leaves us in the dark.

Archaeological excavations suggest that primitive hunter-gatherer groups were more egalitarian than the complex civilizations that emerged after the agricultural revolution. Focusing on the Near East, researchers from Durham University found that societies became increasingly unequal as they transitioned from the Neolithic period into the Iron Age, between 1200 and 900 BC.

In small rural communities, most individual households were more or less identical. However, as the first large cities took shape, those households began to vary drastically in size and shape. Researchers not only found a positive correlation between household size and personal wealth, but also between size and socioeconomic status, political influence, and even health.

It’s difficult to know exactly how the elites of this time lived. But a glimpse comes from the objects they maintained after death. For example, people whom archaeologists and historians generally believe to have been elites of the Hallstatt culture, which was primarily centered around present-day Austria in 1000 BC, were sometimes buried with luxury goods, like intricate bronze vessels, Greek pottery, and silk imported from the East.

In ancient Crete, wealthy women were buried with precious perfumes and bronze or silver jewelry, while their husbands were buried with swords and spearheads — treasures that only a select few could have afforded in life, let alone death.

Roman riches around 1 AD

The city of Pompeii, which was incredibly well-preserved under a thick coat of ash produced by the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, provides a clear window into what it like to be well-off during the turn of the millennium. Once again, data analysis of archaeological sites around the volcano shows that social inequality increased as time went on and the Roman Empire became more technologically advanced.

If you were a rich Pompeiian, you didn’t live in a house but in a domus. The average domus had a surface area of 3,000 square meters. They usually included an atrium, multiple bedrooms and living rooms, servants’ quarters (wealth in Rome was displayed primarily through your servants), studies, and a garden decorated with flowers, frescoes, and sculptures. Oh, and farmland. Lots of farmland.

One of the most obvious signs that you were part of Pompeii’s elite was having running water in your private domus — and sometimes even a small-sized swimming pool. Although Pompeii maintained an extensive plumbing system for about 100 years before Mount Vesuvius destroyed the city, most citizens could only access running water through public fountains.

In 2017, a more vivid image of what it was like to be wealthy in Pompeii was discovered via an inscription in one of the city’s tombs. It described a days-long party thrown by a young, wealthy man. The party included “456 three-sided couches so that upon each couch 15 persons reclined,” the inscription read, adding that the wealthy party-thrower was of such “grandiosity and magnificence” that he had 416 gladiators fight over several days for the partygoers’ entertainment.

Writing for Aeon magazine, Peter Turchin — the mathematical historian — explains that wealth distributions across history are primarily determined by the supply and demand of the labor market. If there is a surplus of labor, the upper class profits while the lower class languishes. But when there is a shortage of labor, it is the lower class who profits, and so the wealth gap shrinks a little.

The population of Rome, writes Turchin, expanded rapidly in the first century AD, cheapening labor and expanding the influence of Roman elites until a plague brought population numbers back down again. The deadly Antonine Plague, which killed between 5 and 10 million individuals, correlated with a rage in wages in one of the most affected areas: Egypt.

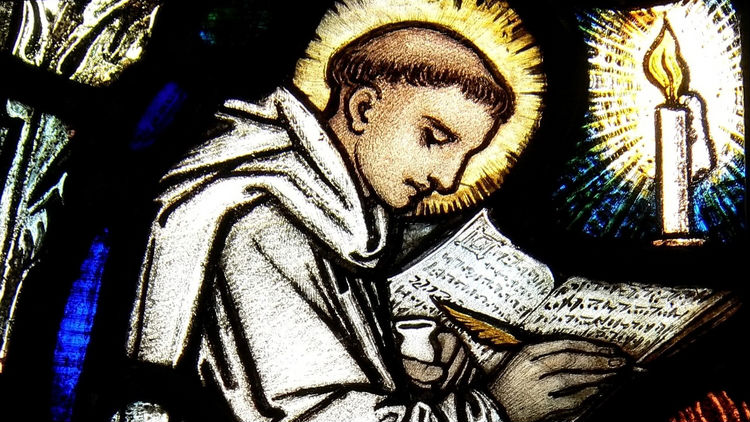

In the period before the Antonine Plague, before Rome turned from a republic into an empire, archaeologists find that upper class people were living a life of arguably unparalleled luxury. Protecting their assets via the Senate, the richest families in Rome were in a constant competition to acquire the finest artwork and throw the biggest, most exotic banquets.

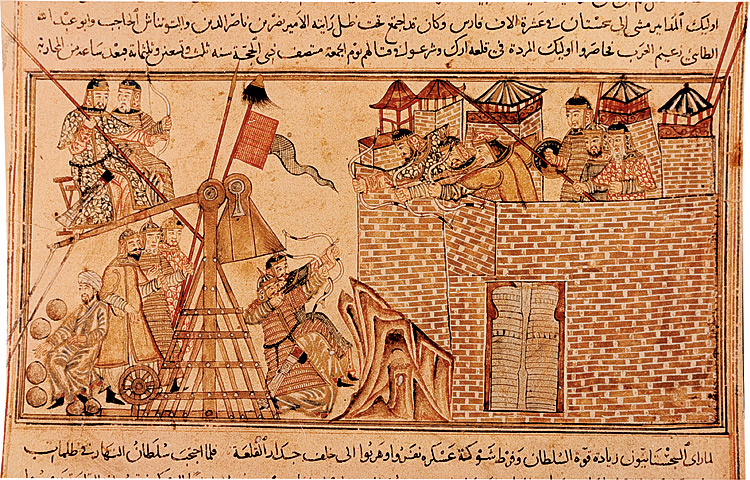

The feudal lords of 1000 AD

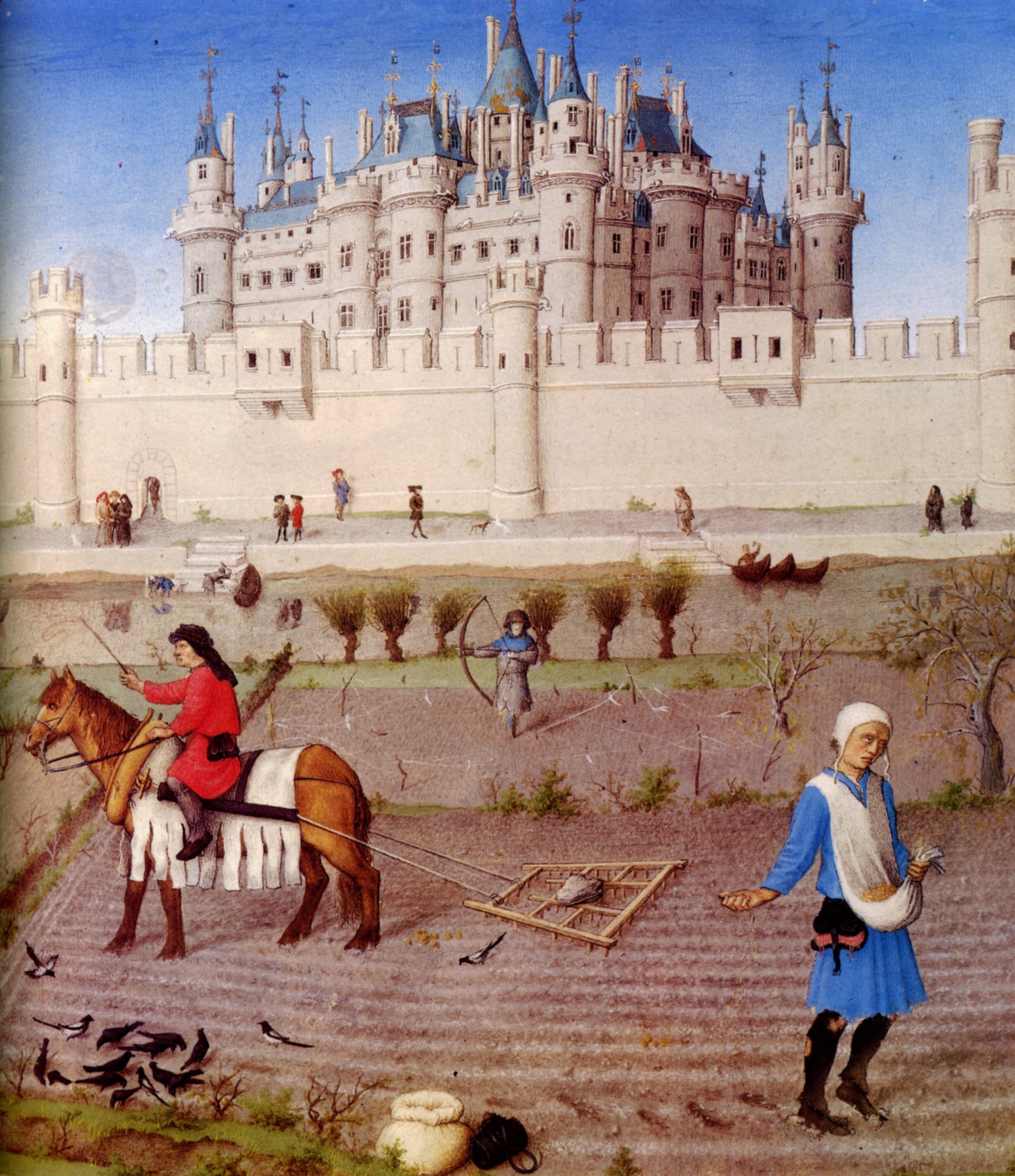

In terms of wealth, as much changed between 1 and 1000 AD as did between 1000 BC and 1 AD. The Holy Roman Empire had officially established itself as the dominant power in Europe, carrying on the legacy of ancient Rome. The Holy Roman Empire was a feudal society wherein noble houses obtained land from the emperor in exchange for paying taxes and providing military services. And while they enjoyed luxuries like access to good food, fine art, and lavish castles and manors, most likely they also had to play administrative or other political roles in the church.

Landowners, in turn, maintained a similar arrangement with their serfs. The serfs cultivated crops for the nobility in exchange for the right to grow some of their own food on the side. Just as the landowners were obliged to present their superiors with armies during times of war, so too were their serfs obliged to take up arms if they were told to.

“The tug of war between the top and typical incomes doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game,” says Turchin, “but in practice it often is.” When England’s feudal population doubled, the demand for work increased. This means that landowners could charge peasants higher rates while also paying fewer benefits, ushering in a “Golden Age” for aristocracy that ended in yet another plague, the Black Death.

Back to the present

Early on in his historical survey of wealth and inequality, Turchin remarks that socioeconomic change need not be spurred by purely economic factors. Culture can also move the markets, often in illogical directions. The uniquely capitalist tendency to view financial success a reflection of merit rather than circumstance, for instance, has built a celebrity culture around businessmen that did not exist in the past.

When we acknowledge the correlation between income inequality and labor market participation, we find that the wealth gap in western countries significantly decreased after World War II, reaching a level that had not been seen since before the American Civil War, the gap started growing again towards the end of the 20th centuries, and continues growing to this day, bringing Musk closer to Musa.