Miniscule tardigrade fossil frozen in amber is over 16 million years old

- Despite their ability to live in extremely inhospitable environments, tardigrades’ bodies rarely fossilize unless they get stuck in amber.

- Recently, a group of researchers uncovered a decently preserved specimen inside a piece of amber found in the Dominican Republic.

- It is the third tardigrade fossil to be described. It was given its own evolutionary genus and species, adding yet another branch to the tardigrade family tree.

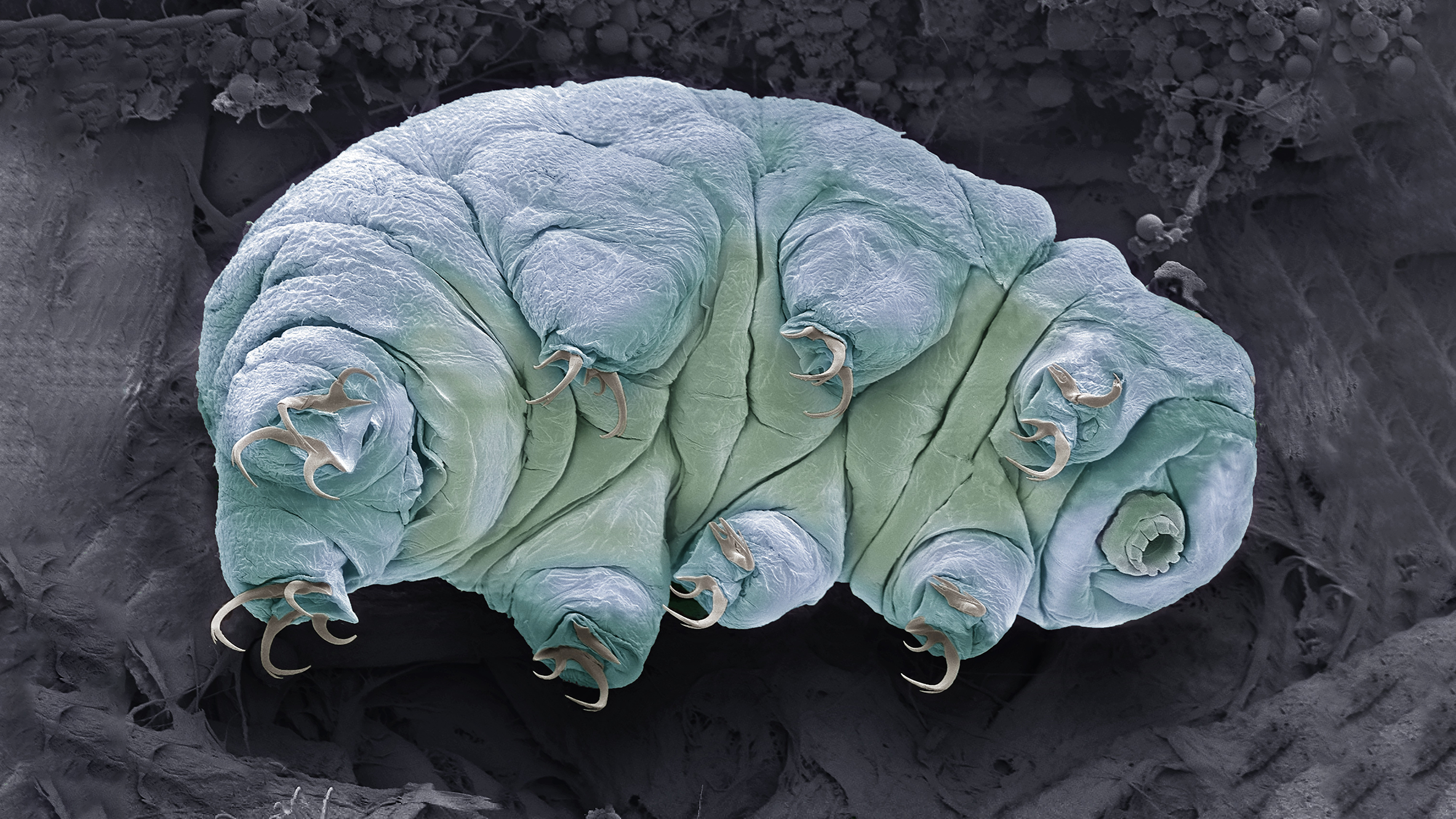

Don’t let their microscopic size mislead you. Tardigrades are some of the most resilient and successful species ever to populate our planet. Also known as water bears for their distinct shape, these eight-limbed organisms have been around for millions of years. During this time, they managed to explore just about every part of the world, from the peaks of the Indian Himalayas to the depths of the Antarctic ocean.

Although the evolutionary history of tardigrades is extensive, it is also shrouded in mystery. Their size, while allowing them to colonize even the most inhospitable ecosystems, also makes it extremely difficult for their bodies to fossilize. With such a sparse geological record, paleontologists cannot help but refer to tardigrades as a “ghost lineage,” a species that seemingly appeared out of nowhere.

To be fair, their origin isn’t all question marks. Calculating the mutation rate of biomolecules, paleontologists can infer that tardigrades must have branched off from other panarthropod lineages before the Cambrian period came to a close. Until recently, only two representatives of a crown group — a collection of fossils linking extant specimens back to their least common ancestor — were described.

Now, that number is up to three. Last week, a team of interdisciplinary researchers from Europe and America announced in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B they had found and identified a brand new tardigrade fossil frozen in a nugget of Dominican amber. The amber dates back to the Miocene age, while the water bear inside appears to have lived during the Cenozoic.

Why water bears fossilize best in amber

To appreciate this discovery in its context, a brief background is in order. The first fossilized tardigrade to be described was named Beorn leggi. It was discovered back in 1964, located inside Canadian amber.

Though not the only place where tardigrade fossils have been found, amber seems to be the material that preserves them the best. Tardigrades, despite being pretty much indestructible when they are alive, lack hard tissue that can petrify upon death. Consequently, the only way in which they can be preserved is if they managed to get caught in tree resin, which the passage of deep time turns into amber.

While B. leggi was the first tardigrade fossil to be described, that description was not very good. Unable to take high-resolution images of their subject, paleontologists failed to place the fossil into any existing branch on the tardigrade family tree. Until a future discovery can help us fill in the blanks, B. leggi remains in the freshly erected placeholder family known as Beornidae.

It took almost four decades before the next tardigrade fossil could be identified. This specimen, christened Milnesium swolenskyi by its discoverers, was found in New Jersey amber. Thanks to its adequate preservation, the fossil could be dated. It was around 14 million years older than B. leggi and was assigned to the Milnesiidae family.

M. swolenskyi was special insofar as its body plan resembled that of an extant member of the Milnesium family. The modern and ancient specimen have similarly shaped claws, and their mouths are fitted with no less than six oral papillae or feeding structures. This, its discoverers stated at the time, indicated that the morphology of tardigrades remained unchanged for at least 92 million years.

Discovering a new genus

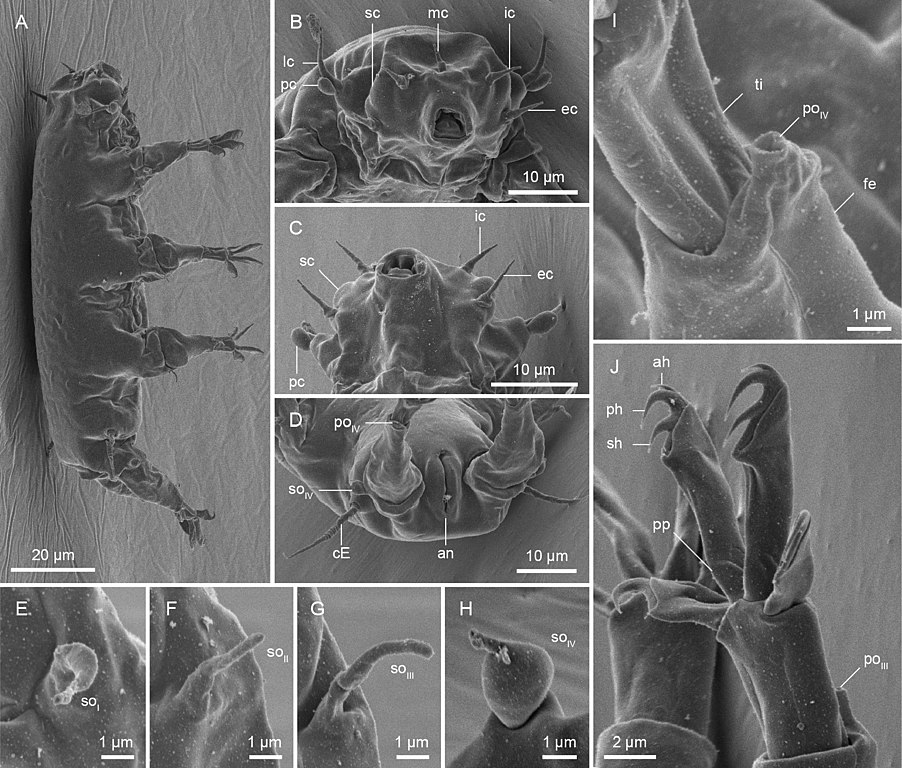

The tardigrade fossil recently found in the Dominican Republic may not be as old as some of the previous discoveries, but it can still tell us a number of things about the evolutionary history of this elusive animal. In fact, the morphology of the fossil was so perfectly preserved that researchers were able to erect an entirely new genus and species: Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus. P. chronocaribbeus was placed in the superfamily Isohypsibioidea, an assessment that wasn’t easy given the difficulty of studying the morphology of microscopic fossils.

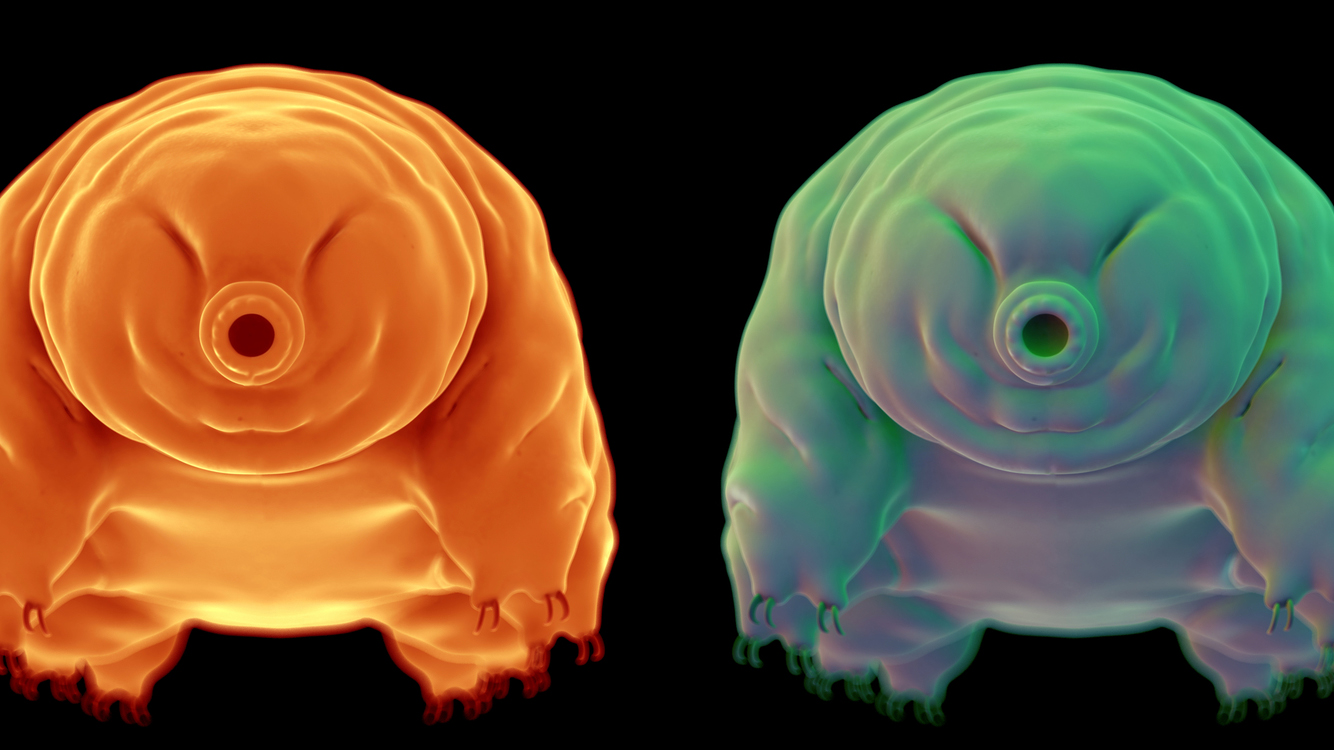

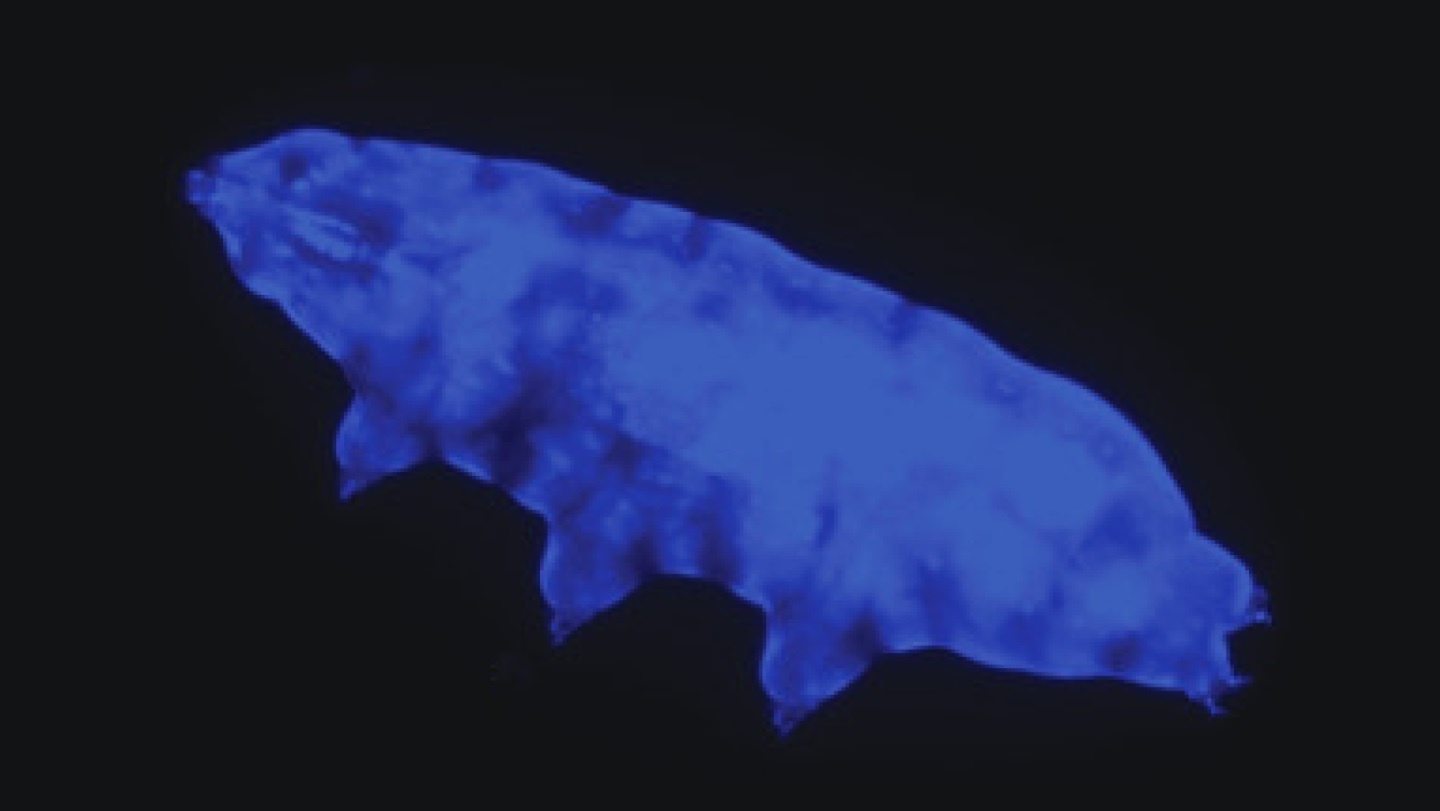

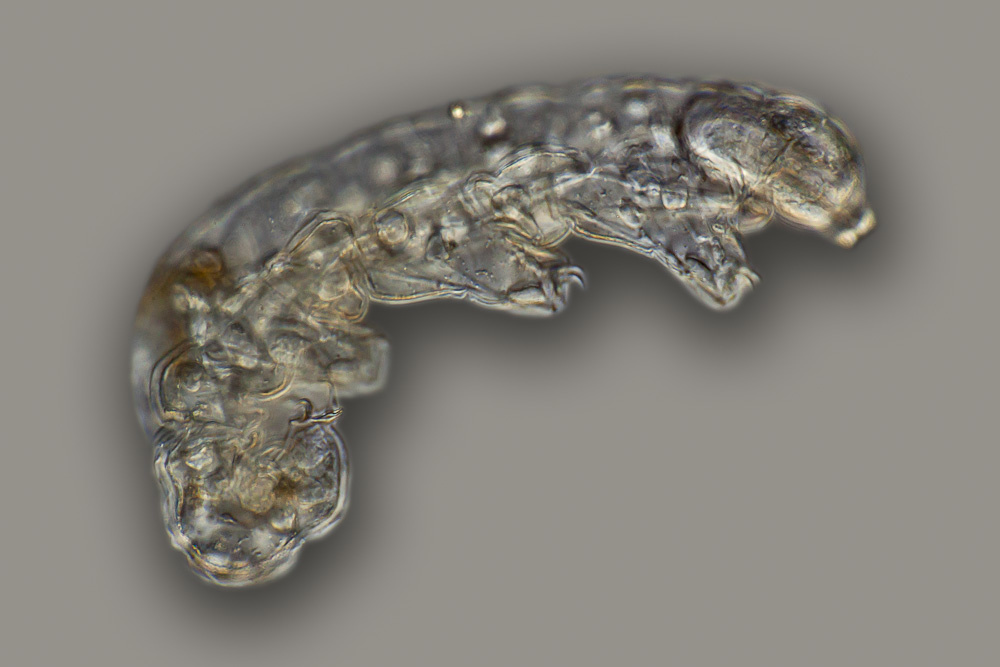

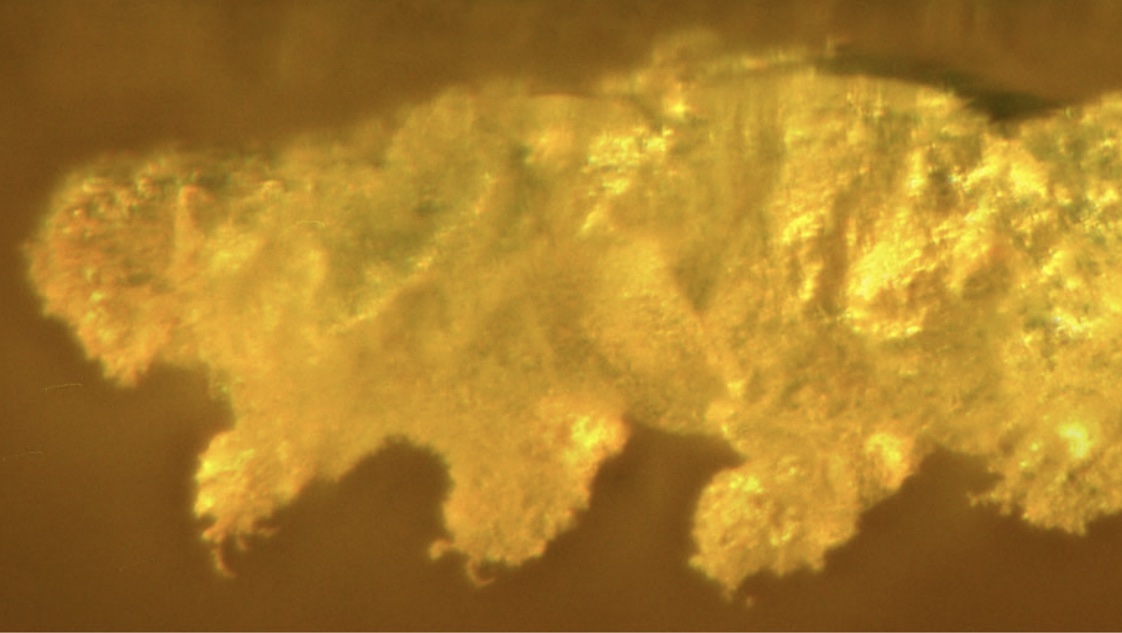

In order to identify their find, the researchers used a variety of measurement techniques. Mounting Paradoryphoribius to a slide, they studied the fossil’s morphology using transmitted light microscopy as well as confocal fluorescence microscopy, which enhances images using a laser.

Comparing the fossil’s features with those of other tardigrades, the researchers found that Paradoryphoribius was both like and unlike its evolutionary relatives. Its claws and spinal canal are similar to that of the genus Doryphoribius. But unlike Doryphoribius, which has multiple, granular-shaped teeth, Paradoryphoribius has only one toothlike appendage.

Tardigrade fossils are hard to come by, but each new find adds a piece to this largely unsolved evolutionary puzzle. With the discovery of Paradoryphoribius, the species’ family tree has grown another branch, giving paleontologists hope that — one day — they will finally be able to unravel the ghostly origins of the water bear.