The mummy’s curse might be real — but it’s caused by a fungus

- After the opening of King Tut’s tomb a century ago, the public became enthralled with the idea that many of those who entered were stricken with a a “mummy’s curse” and died.

- There might be a scientific explanation. Shuttered, isolated tombs could grow dangerous fungal molds, particularly Aspergillus flavus, that could harm people with weakened immune systems.

- Aspergillus also might have contributed to the deaths of ten conservationists who opened the tomb of Polish King Casimir IV Jagiellon in 1973.

One hundred years ago this past February, English archaeologist Howard Carter entered the sealed burial chamber of the legendary Egyptian ruler King Tutankhamen, revealing its decrepit, yet dazzling innards to the modern world for the first time — and as popular myth holds, unleashing a deadly “mummy’s curse” upon those who entered.

As prominent figures and archaeologists visited the tomb, some ended up suffering untimely deaths in the following days, weeks, and months, mainly from heart attack, exhaustion, or pneumonia. The media reported every one and sensationally played up the notion that a mummy’s curse may be responsible. Many decades later, researchers have raised and debated a scientific explanation to supplant the supernatural one: Could the curse be caused by a fungal mold?

More on that in a bit, but first, the mummy‘s curse was likely not as deadly as the early 20th century media reports made it out to be. In 2002, Professor Mark Nelson of Monash University published an analysis showing that people who visited King Tut’s tomb during its initial opening didn’t live much shorter lives than control subjects who were in Egypt at the same time but didn’t visit the tomb. However, the inherently sketchy data used for Nelson’s study did leave open the possibility that something pernicious might have been at play.

The fungus among us

That pernicious something could have been the fungal mold Aspergillus flavus. Scientists zeroed in on this particular suspect after another apparent mummy’s curse was set loose in 1973. That May, a team of 12 conservationists opened the tomb of Casimir IV Jagiellon, a famous King of Poland from the 15th century. Ten of them died over the ensuing weeks and months.

Microbiologist Bolesław Smyk later found the aforementioned A. flavus throughout the tomb, and speculated that it may have contributed to the deaths. The fungal species is the second-leading cause of aspergillosis in humans, a potentially deadly disease that most frequently affects the lungs of those with weakened immune systems. In milder cases, the condition can cause acute inflammation and breathing problems, but in harsher instances, the fungus can grow in the lungs and even spread throughout the body. In 1998, Dr. Sylvain Gandon, a researcher at the Laboratoire d’Écologie in Paris, showed that fungal spores can lay dormant for hundreds of years, retaining their potency.

These collective findings help us begin to paint a scientific picture of the mummy’s curse: In rare instances, Aspergillus can proliferate throughout a tomb, perhaps growing on grains left inside or on the mummies themselves, and then the fungal spores bombard the first people to disturb the resting place in hundreds of years as outside air roils the enclosed environment. The elderly and those with weakened immune systems would be most susceptible, perhaps developing a lung infection that leads to breathing problems and eventual death. Healthy individuals, on the other hand, might only suffer slight symptoms or none at all.

Researchers writing in a 2003 correspondence to The Lancet noted that this theory fits with the highly publicized death of Lord Carnarvon, who was one of the earliest entrants into King Tut’s tomb. He passed away five months after entering, supposedly of pneumonia.

“Spores of Aspergillus can remain dormant in the lungs of infected individuals for extended periods before being activated,” they wrote, adding, “On March 17, 1923, The Times of London reported that Lord Carnarvon suffered from ‘pain as the inflammation affected the nasal passages and eyes.’ This description is consistent with invasive Aspergillus sinusitis with local extension to the orbit.”

They concluded:

“Lord Carnarvon could readily have inhaled contaminated grain dust as the sealed tomb was broken into. Since his car accident in 1901, he had had numerous chest infections and would have been especially susceptible to the toxic mold. Indeed, this increased susceptibility could explain why so many others did not succumb to the same infection upon entry.”

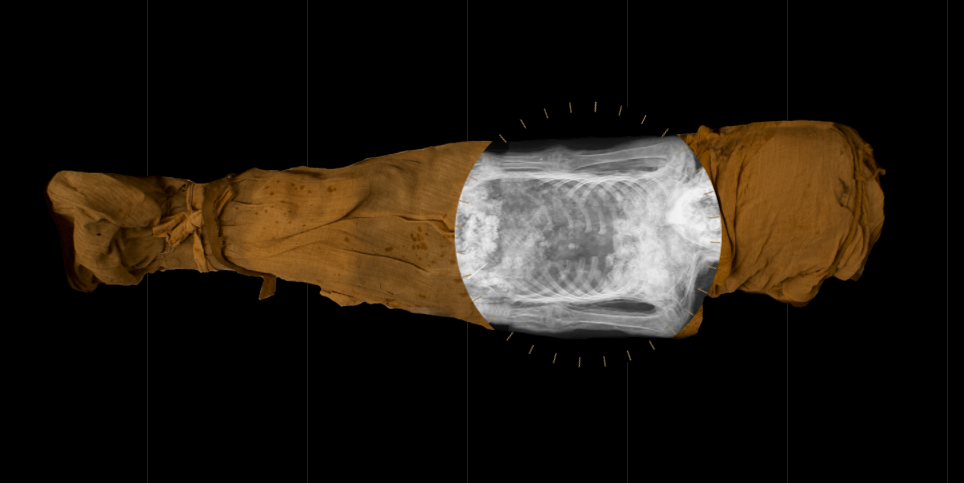

Modern mummies

Last month, Mexican experts expressed concern that a traveling display of mummies from the 1800s could pose a danger to the viewing public after fungal growths were spotted on one of the cadavers. However, as the mummies rest behind an apparently concealed case and are kept in a public area with decent air flow, health concerns are minimal. The mummy’s curse may be genuine, but also situational and extremely rare.