Leningrad: What was it like to live through history’s deadliest siege?

- Due to modern technology like canons and aircraft, sieges became both rarer and deadlier.

- The barbaric conditions of the Siege of Leningrad inspired a handful of writers to record their suffering.

- Today, their diaries offer insight into what it was like to live through a destructive urban conflict.

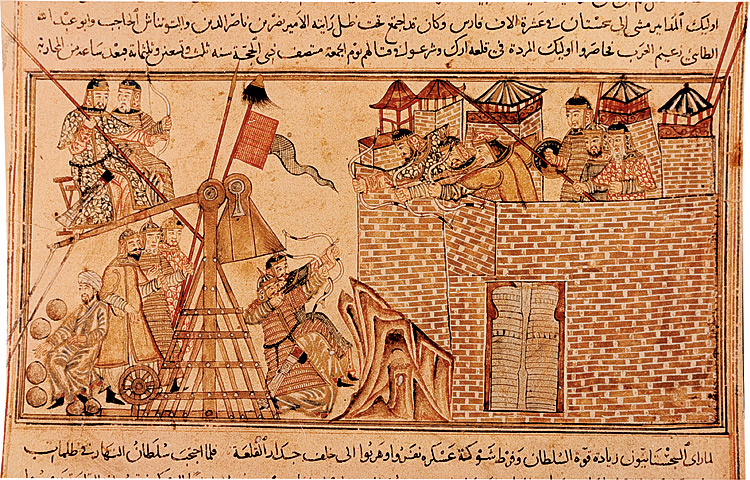

Sieges are a form of low-intensity conflict where one military force surrounds the stronghold of another. Victory is to be achieved not through battles, but by cutting off an enemy’s supply lines. The hope is that, in time, the inhabitants of the besieged stronghold become so famished and psychologically broken that they willingly surrender themselves to their opponent.

In medieval times, sieges took place frequently, and were an important component of military campaigns between Europe’s rulers. This changed during the time of Napoleon, when the invention of canons rendered even the most fortified cities vulnerable to direct attack. During the 20th century — when canons were replaced by tanks and aircraft — sieges became even less frequent.

But while the frequency of sieges decreased, their death tolls did not. The Siege of Leningrad, which lasted from September 1941 until January 1944, and led to the deaths of some 800,000 civilians, is remembered as the most destructive urban conflict of all time. Some historians have argued the nature of the siege and its tactics were such that it should be classified not as an act of war, but genocide.

Life inside a besieged city like Leningrad was unimaginably difficult. Citizens felt the desire to live on wane with each passing day. Starvation gradually robbed them of their ability to laugh or love, and the sight of death became so commonplace that it ceased to frighten them. For what it’s worth, the siege also inspired a few eloquent writers to record the bleak conditions in which they lived.

Inside the Siege of Leningrad

On June 22, 1941, Nazi forces invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet government, which had signed a non-aggression pact with Germany just two years prior, was woefully unprepared to ward off this surprise attack. By early August, Hitler’s soldiers approached their objective: the city of Leningrad, formerly known as Saint Petersburg, one of the country’s most important industrial centers.

The Germans had moved quickly, but their signature speed came at a cost. Russia was a lot more spread out than western Europe, and its climate was much, much harsher. Ill equipped to fight through the coming winter, Nazi officers decided they would take Leningrad via siege rather than through a military confrontation — a decision that conjured hell for both sides.

Aside from severing Leningrad’s supply lines, the Germans also subjected their enemies to continuous yet largely unpredictable rounds of artillery bombardment. Early in the siege, one of these bombardments destroyed a warehouse complex near Zabalkansky Prospekt, significantly reducing the city’s already dwindling supply of flour and sugar.

Desperate times called for desperate measures. Citizens supplemented their daily bread rations with grist or wood shavings, and boiled glue to extract microscopic amounts of calories. In lieu of meat, custodians at the Leningrad Zoo had to trick their carnivorous animals into eating hay, which they soaked in blood or bone broth before sewing it into the skins of smaller animals.

The birth of the “siege man”

Although survival became a full-time job, some Leningraders found time and strength to write. Today, their diaries form an important and moving chapter of Russia’s literary canon. One of the most famous authors was an 11-year-old girl named Tatyana Savicheva, whose brief, hand-written letters document the deaths of her sister, grandmother, brother, uncle, and mother.

The last two notes tell you all you need to know. One reads, “Everyone died.” The other, “Only Tanya is left.” Savicheva managed to escape Leningrad, but died of tuberculosis mere months after the siege was lifted. A symbol of civilian casualties, she eventually received her own memorial complex, and her letters were used as evidence against Hitler’s right-hand men during the Nuremberg Trials.

Another writer who shaped our memory of the Siege of Leningrad is the Russian literary critic Lidiya Ginsburg. Her book, Blockade Diary, attempts to explain how living through a siege changes how you view the world. Having studied at Leningrad’s Sate Institute of the History of the Arts alongside Boris Eikhenbaum, Ginzburg paints a startlingly methodical picture of this otherwise chaotic period.

Throughout the work, Ginzburg sketches the psychological profile of a new sub-species of human that she refers to as the “siege man.” Described by the author as an “intellectual in exceptional circumstances,” he (or she) is both less and more than human. Though they are forced to make do with barbaric conditions, these conditions also cause them to experience the most refined of spiritual revelations.

Lidiya Ginzburg’s Blockade Diary

An underappreciated heavyweight in the worlds of critical and literary theory, Ginzburg’s smallest observations often leave the biggest impacts. She notes, for instance, how people living under siege no longer separated Leningrad’s cityscape in terms of its historical neighborhoods. Instead, areas were distinguished based on how susceptible they were to being bombarded.

While death loomed around every corner, Leningraders always found a way to expunge its presence from their minds. New routines provided them with a subconscious sense of comfort: “Many even thought that it was the action of descent and sitting in the cellar that guaranteed a happy outcome; it never occurred to them that this time the house might have survived just as well if they had stayed upstairs.”

The siege also affected people in other, less obvious ways. Keenly interested in psychology, Ginzburg saw that Leningraders were placed in situations they had not experienced since birth. Like small children, they were incapable of providing their own nourishment. And as their starvation worsened, activities they had taken for granted as grown-ups — like walking or sitting still — suddenly became difficult again.

Despite its genius and historical significance, Blockade Diary is hardly known outside of academic circles. This is perhaps because, like other such diaries, its distribution was long suppressed by the Soviet government to hide the country’s military failures. Yet those who lived through the siege were most certainly strong in spirit and will, and the fact that Leningrad was never taken only serves to reinforce this.