Iran’s Persian Constitutional Revolution reveals the complicated relationship between Islam and democracy

- The Persian Constitutional Revolution laid bare the divided loyalties that occur when religion and geopolitics collide.

- For instance, American Christian missionaries stationed in Iran were torn on whether they should help their neighbors or remain uninvolved in a foreign conflict.

- Islamic clerics were also divided. They disagreed on whether popular sovereignty was a God-given right, or at odds with their core faith.

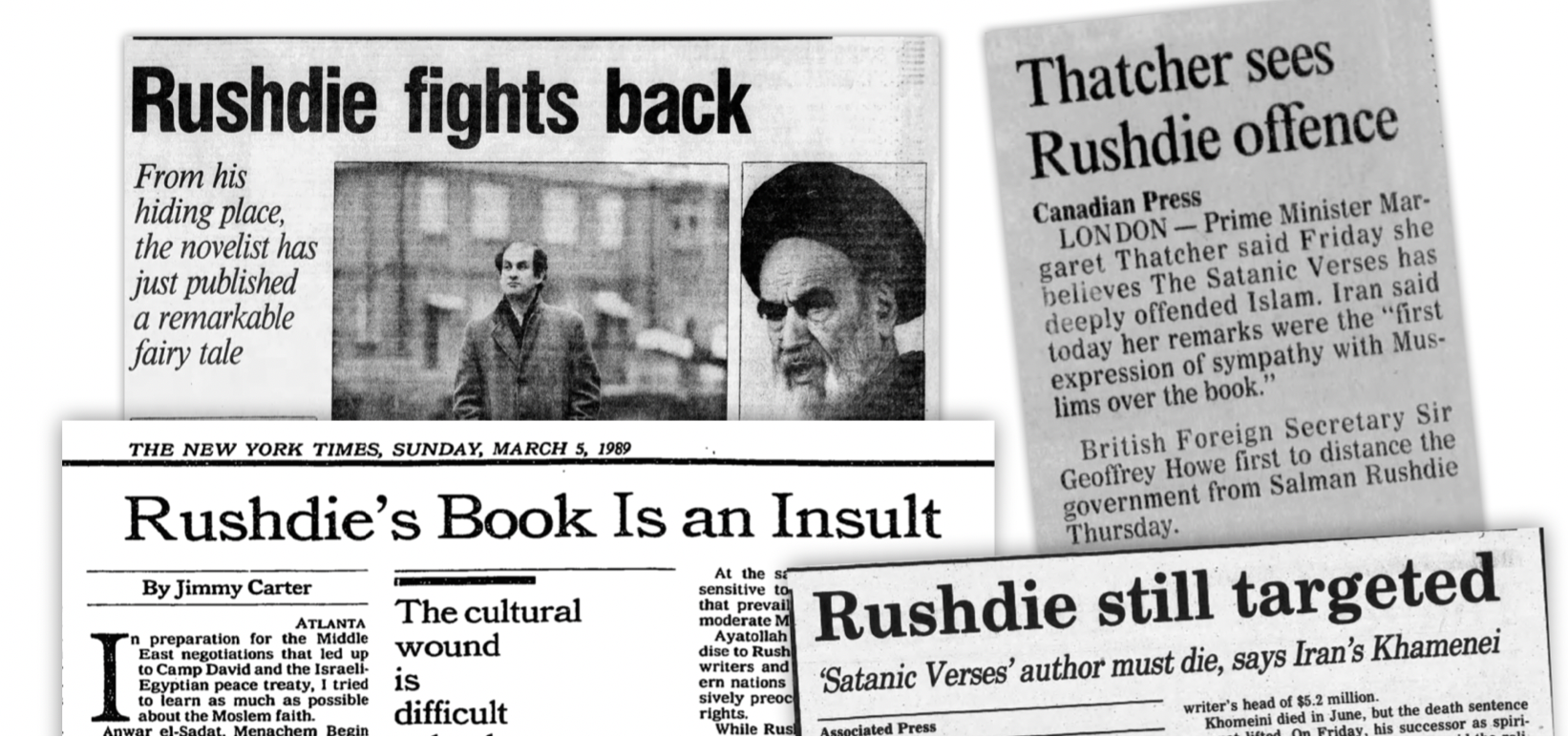

With the recent terrorist attack against Israel by Hamas, global attention inevitably will shift to Iran and what role it played, if any, given that it has been one of the group’s major benefactors for about 30 years. But that funding has come from the government, not the people. Indeed, the people of Iran have staged high-profile protests against their oppressive government over the past year following the murder of Mahsa Amini by the “morality police.” To gain a better understanding of Iran today, we need to delve a bit into its history.

A history of revolutions

Important revolutions are often remembered through engaging but highly simplified narratives. Usually, they are about ordinary people standing up against a despotic ruler. The American Revolution was fought between the American colonies and the British Empire. In the French Revolution, the citizens of France demanded the abdication of Louis XVI. During the Russian Revolution, the Russians demanded the same thing of their czar, Nicholas II.

On a basic level, all of this is more or less correct. But upon closer inspection, the simplified narratives start to fall apart. The American Revolution was, strictly speaking, not just fought between the Americans and the British; England’s biggest enemy, the French, were also involved, primarily through the support of the Marquis de Lafayette. The French Revolution, meanwhile, ate its own tail during the Committee of Public Safety’s Reign of Terror. And the Russian Revolution was, in truth, not one but two revolutions, both with different outcomes.

In his book War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy explains that past events are way too complex to be distilled into straightforward stories like those mentioned above. The only way to truly understand how history unfolds, he argues, is to stack up the biographies of every person who ever lived.

Persian Constitutional Revolution

Iranian American historian Reza Aslan may well have used Tolstoy as a guiding light while writing his latest book, An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville. Published last year, the book tells not only the story of the titular Baskerville — a Nebraskan missionary sent to Iran on the eve of the Persian Constitutional Revolution — but also the stories of the many students, politicians, and freedom fighters that he came into contact with over the course of this life-changing (and, ultimately, life-ending) journey.

In the telling, Aslan demonstrates that human history is not just shaped by faceless forces like economics or logistics, but also an intricate web of personal and professional relationships. In the case of the Persian Constitutional Revolution, this web of relationships resulted in unlikely and often temporary allegiances, not to mention factions-within-factions.

Howard Baskerville could not have arrived in Persia, modern-day Iran, at a more uncertain and dangerous time. Following global trends, the country had recently managed to establish a parliament — perhaps the defining moment of the Constitutional Revolution — but its legitimacy was tested by the shah, Mohammed Ali.

This largely bureaucratic dispute took a violent turn when, in 1907, a package bomb was thrown into the shah’s car as he was leaving Tehran. Parliament moved to prevent Mohammed Ali, who survived the attack, from ordering the kind of extrajudicial arrests and executions that usually took place when the head of state was attacked. To everyone’s surprise, the normally despotic shah released the suspects and even agreed to remove from his court advisors that parliament distrusted.

Skeptics feared the shah’s cooperation was no more than a ruse, and they were right. Once the constitutionalists had let down their guard, Mohammed Ali declared himself the one and only ruler of Iran. He distributed weapons to his supporters in the countryside and mobilized his elite fighting force, the Cossack Brigade, headed by imperial Russian officer Vladimir Liakhov. Before long, his forces had most of the country under his control. The only remaining constitutional stronghold was the city of Tabriz, the city that Baskerville was now living and working in.

Baskerville became a missionary after studying at Princeton. He had wanted to go to China, but the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Ministers sent him to Tabriz instead. There, the 22-year-old joined the faculty of the American Memorial School. Run by a seasoned missionary named Samuel Wilson, the school struggled to convert the city’s Muslim residents, for whom Islam was both their faith and cultural identity. It did, however, provide a quality education for upwardly mobile and progressively minded Iranian families; in class, topics like civil rights were discussed with religious fervor.

One might think that Americans in Iran wholeheartedly supported the Persian Constitutional Revolution. However, things were not so simple. The Presbyterian Board forbade missionaries from intervening in “temporal matters” while abroad, not only because doing so could compromise the global standing of the U.S. government, but also because worldly affairs were of no concern to people doing God’s work.

In practice, it’s hard to remain neutral when you become attached to a place and involved in a community. Though American by blood, Wilson’s wife and children were all born and raised in Persia and considered themselves Persian, too. And while the teachers refused to take an active part in Tabriz’s struggle against the shah, they still felt obliged to reduce suffering by feeding the hungry and caring for the wounded.

But Baskerville felt he needed to do more. At the request of Sattar Khan, a highway robber who had become the leader of the constitutionalist forces, he started sneaking into the library of the American consulate to dig through the Encyclopedia Britannica for instructions on how to make explosives or deploy artillery. When the manager of the library got on to Baskerville, he reminded him and other missionaries that “insurrection against an oriental government” was a “capital crime.”

Undeterred, Baskerville not only continued his research but also took up arms. He became Sattar’s second-in-command, and died leading a key battle against the shah. When questioned about the integrity of his decisions, he said that he did not see a contradiction between his beliefs and his actions:

“I cannot remain calm and watch indifferently the sufferings of people fighting for their rights. I am an American citizen and I’m proud of it, but I’m also a human being and cannot help feeling deep sympathy with the people of the city… I am not afraid of any fatal consequence and I am determined to serve the national cause of Persia.”

Ayatollah versus ayatollah

The Americans were not the only ones who turned on each other during the Persian Constitutional Revolution. The same goes for the country’s own clerics. Often pictured as homogenous by outside observers, the mullahs — or ayatollahs, as they are also called in Iran — similarly disagreed on whether to support the royalists or the constitutionalists.

As Aslan writes in An American Martyr, progressive clerics played a key role in rallying the people of Iran against the shah. Mohammed Ali’s father, Mozaffar ad-Din, was criticized by religious leaders in the Arab world. One of them, Sayyid Jamal ad-Din Asadabadi, known as Al-Afghani, condemned his “dereliction of duty in guarding his subjects against injustice.” Al-Afghani was a founding figure of Islamic modernism, a movement that saw the religion as a vehicle for social change and a shield against despots.

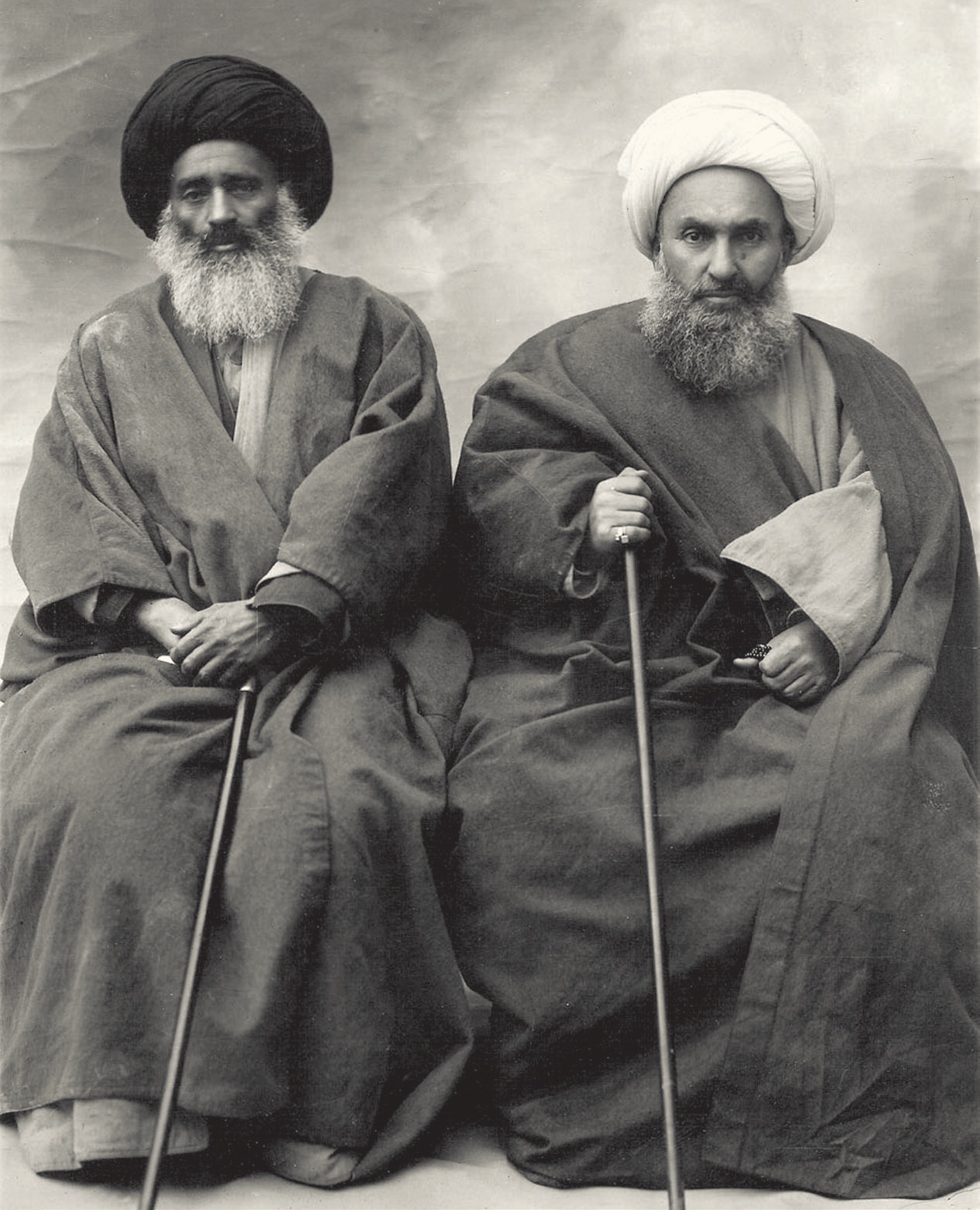

When Mohammed Ali took back control of Iran after fooling the constitutionalists, Liakhov’s Cossack Brigade laid siege to the parliament building. The constitutionalists held up inside were led by two ayatollahs: Muhammad Husayn Tabatabai and Seyyed Abdollah Behbahani. Both had urged for a peaceful resolution and continued to do so while under fire. When the building was destroyed, the ayatollahs were chained and taken to the shah, who had them beaten and humiliated by his soldiers.

By Mohammed Ali’s side stood a colleague of Tabatabai and Behbahani, the cleric Fazlollah Noori. An anti-constitutionalist, Noori felt that “representative government is contrary to the laws of Islam,” and urged the shah not to compromise with the rebels. Under his watch, fatwas (clerical rulings) were issued calling for a jihad against Sattar Khan and his supporters. “Muslim,” one of the many flyers distributed through Tabriz read, “Make an effort! Where is your honor? Islam is on the verge of being lost. Jihad is mandatory for every one of you in order to erase the root of these religionless people from the earth.”

Meanwhile, pro-constitutionalist clerics were issuing fatwas against the royalists. The grand ayatollahs of Najaf compared Sattar Khan and his followers to Husayn ibn Ali, the grandson of the prophet Mohammed and a hero in Shi’a Islam who symbolizes resistance and self-sacrifice in the name of injustice. To cooperate with the shah and conspire against the constitutionalists, they said, was to betray Husayn. Another fatwa said that paying taxes to the state while the shah was in power was “one of the greatest sins.”

Islam and democracy

Disagreement on the link between Islam and democracy continues to play an important role in Iran to this day. Ruhollah Khomeini, who founded the Islamic Republic and became its first Supreme Leader, believed that clerics should act on God’s behalf in the present moment rather than wait for future judgment. This belief, which became the theological basis for his absolute rule, had no basis in Shi’a scholarship and continues to be questioned by clerics inside and outside the republic, some of whom are once again advocating compromise and siding with protestors.