Ichthyosaurs were no gentle giants

- Ichthyosaurs were massive marine reptiles that ruled the oceans more than 200 million years ago.

- Ichthyosaur fossils have been poorly preserved, limiting our understanding of these animals.

- In a new study, scientists report the discovery of a huge ichthyosaur tooth that is making experts rethink what we know about ichthyosaur size and ecology.

In the summer of 1990, a group of paleontologists high in the Swiss Alps excavated an enormous, broken tooth. Thirty-two years later, the researchers have concluded that the fossils came from a species of ichthyosaur (Greek for “lizard fish”), massive marine reptiles that dominated the oceans during the Triassic period. The tooth, along with rib fragments and a vertebra, came from a super-giant group of ichthyosaurs. The creatures ranged from 50 to 66 feet in length, giving the T. rex and the blue whale some company on the list of the largest creatures that have ever lived.

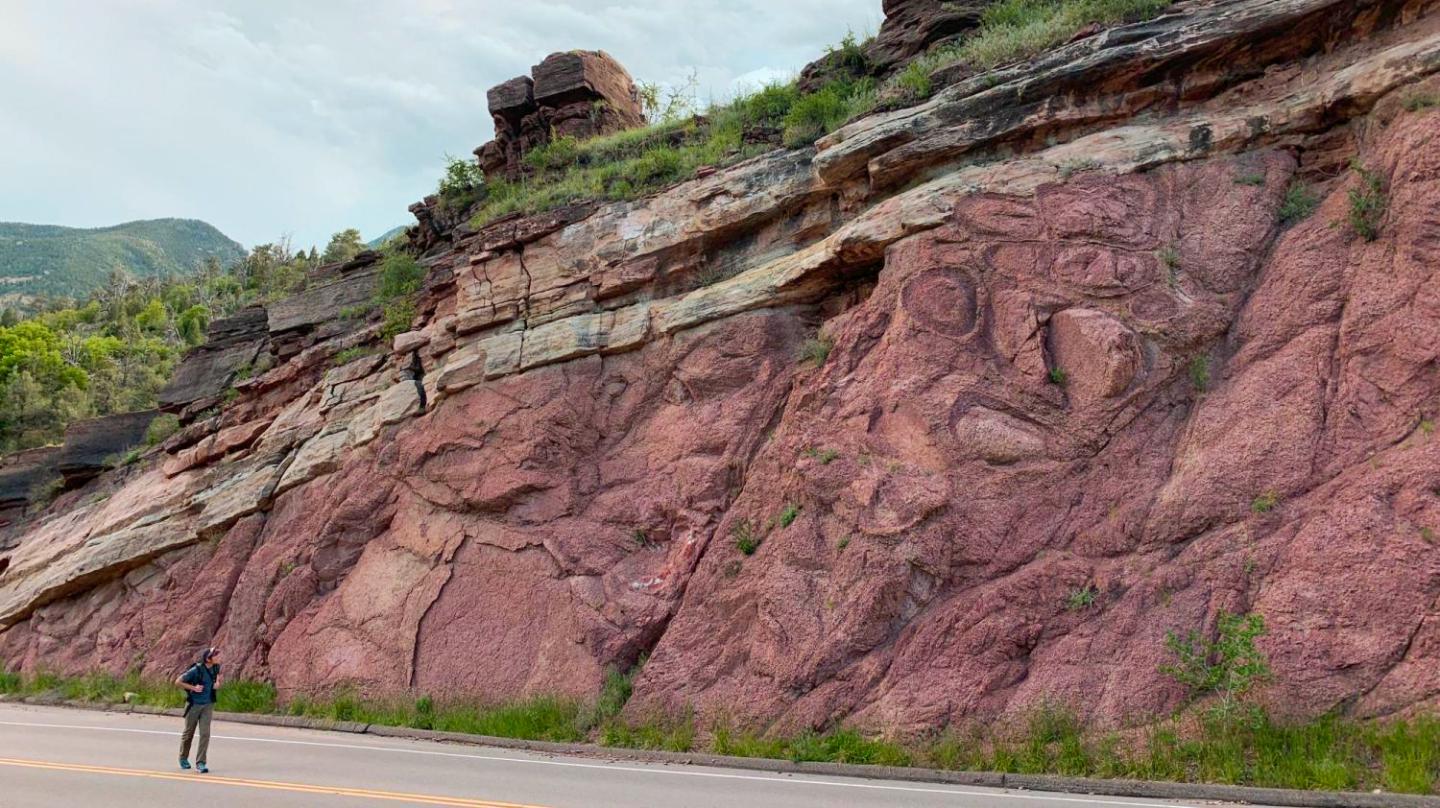

The fossils were found in the Kössen Formation, a geological formation that spans the Alps from Germany to Switzerland. The limestone rock that preserves such fossils once covered the sea floor, but when the Alps began to form and fold, they lifted the stone thousands of feet higher.

The findings, reported in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, widen our understanding of the immensity of these sea creatures, teaching us new things about how they ate and lived.

The great dying made way for the ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs were among the first animals to repopulate the earth’s oceans after the Great Dying, a massive extinction event that occurred some 250 million years ago. Rapid global warming, likely due to greenhouse gas emissions from volcanic eruptions, raised the Earth’s temperatures by 18 degrees fahrenheit (10 degrees celsius).

Two-thirds of terrestrial life perished in the Great Dying, including plants, insects, and microbes. But the catastrophe in the oceans was greater still. The warmer water gets, the less dissolved oxygen it can hold, and as the Earth warmed during the Great Dying, its oceans lost around 80 percent of their oxygen. The vast majority of marine life died. Between 81 percent and 96 percent of marine creatures suffocated to death. This staggering loss of life makes our current extinction event seem mild in comparison.

The Great Dying marks the end of the Permian period and the onset of the Triassic, which spans the period from 250 million to 238 million years ago. At this time, the oceans were essentially barren. Temperatures took millions of years to stabilize, but once they did, marine ecosystems were open to colonization by land reptiles. Ichthyosaurs were one of the first groups of reptiles to go exploring underwater. They went on to dominate the ocean throughout the Triassic period.

Large yet hard to detect

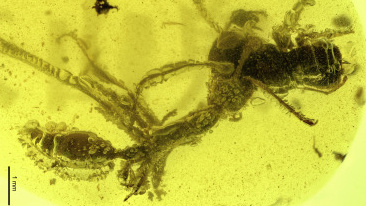

Paleontologists have found fossilized remains of ichthyosaurs all over the world, but these scattered specimens tend to be incomplete or poorly preserved, a situation the study authors describe as “a peculiar feature: ample but tantalizing evidence of giant ichthyosaurs.”

Essentially, scientists had enough evidence to know that mega-creatures the size of today’s blue whales dominated the oceans for tens of millions of years. But we know nothing else about these marine giants — things like what they preyed on, or where they lived. The reported findings came as a welcome addition to a rather paltry record of one of our Earth’s largest creatures — a lack of information that Martin Sander, a co-author of the paper, described as “an embarrassment for paleontology.”

Ichthyosaur Ecology 101

The Swiss megatooth is four inches in length, even with its crown missing, and boasts a diameter doubling the size of any marine vertebrate’s tooth. Along with the tooth, the team excavated enormous vertebra and rib fragments. In total, the fossils came from three different ichthyosaur individuals, none of which resembled any known species. All three individuals were large and long, with the toothed giant clocking in at some 66 feet in length. Still, none of the three ichthyosaurs could compete with the size of a relative found in the Bristol Channel whose length is estimated at 85 feet. Our toothed friend was still quite large, though, and it happened to have some gigantic teeth.

Regardless of its size, the tooth is a huge find for scientists, who have long wondered whether giant ichthyosaurs had teeth at all. Before this finding, researchers grudgingly concluded that since their remains rarely included teeth, large ichthyosaurs might have been suction feeders, acting like giant vacuum cleaners sucking up goodies from the water. In fact, modern blue whales, which are the only living creatures similar in size to ichthyosaurs, use this foraging method to sustain their 80-foot-long, 200 ton bodies.

Together with the discovery of a Himalayasaurus jaw, the Swiss tooth provides solid evidence to refute the suction-feeding theory and completely rewrite the ecology of giant ichthyosaurs. In fact, the researchers suggest that the tooth was probably useful for hunting smaller ichthyosaurs and even giant squid, painting a picture of a fearless creature with all the size of a blue whale, plus a ferocious bite.